A Hurricane Sandy Story

I’m tagging along as Adrianna Zito-Livingston gives a tour of the Conservancy’s South Cape May Meadows Preserve at the far southern tip of the Jersey Shore, where the Atlantic Ocean meets the Delaware Bay. This is one of the most important stopover sites for migratory birds in the world, but no one in the group in front of me has binoculars or a scope, let alone a field guide tucked under their arms.

That’s because they’re not here for the birds; they’re here for the storm.

Well, more specifically they’re here to see the place that protected local communities from Hurricane Sandy—and its 10 inches of rain and three-and-a-half feet of storm surge—five years ago this week.

Not that Zito-Livingston, the preserve coordinator since 2007, is complaining about her audience’s interest in weirs over warblers.

“Definitely not,” she says. “Managing South Cape May Meadows in a post-Sandy world and watching storms increase in frequency and severity, it’s really exciting and refreshing to see the level of interest people have in the preserve and its restoration.”

A (Very) Brief History of a Restoration

First, a little background. In 2005, the Conservancy, the Army Corps of Engineers, the New Jersey Department of Environmental Projection, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and other local partners embarked on an ambitious project to restore Lower Cape May Meadows area. They widened the beach, restored the dunes and the freshwater wetlands at the Conservancy’s preserve and neighboring New Jersey’s Cape May Point State Park.

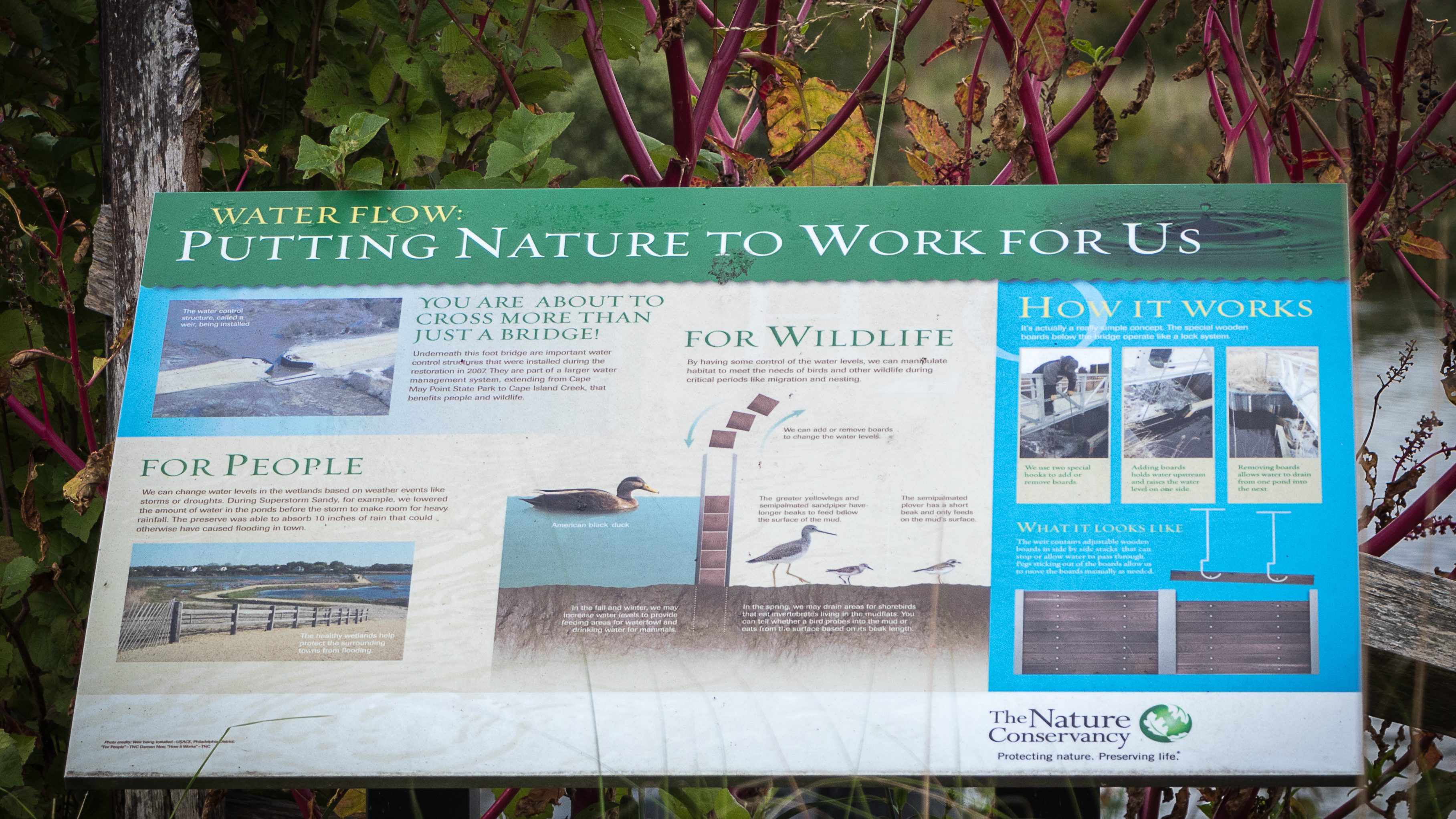

One of the key goals of the project, in addition to restoring healthy habitats, was to manage the flow of water through this part of Cape May, which had been prone to flooding during storms and extreme high tides. (The restoration itself was completed in 2007.)

“Thanks to the restoration, this preserve has a lot of special features,” notes Zito-Livingston. “And the way it connects to local municipal properties and the state park is one of the most important, in terms of connecting habitats but also in managing water. And water now moves through this property as it would have before this area was developed. The [natural flows] were recreated through the restoration project and we manage water levels with a series of weirs.”

Sandy Tests the Dunes and Wetlands

Fast forward to 2012, when Hurricane Sandy dropped about 10 inches of rain and pushed three-and-a-half feet of storm surge on this area. Still, says Zito-Livingston, “we were lucky. We were not directly hit [by the storm]. We didn’t see the most severe impacts, but the wetlands and dunes did receive their first real test since the restoration was finished in 2007.”

Additionally, notes Zito-Livingston, the wide beach and the 18-foot dunes held up as well. “The beach was over washed and water flooded up onto the dunes, but it didn’t overtop or breach them. In previous storms before the restoration was carried out, the community saw a lot more frequent flooding that interfered with local infrastructure.”

While damage to the surrounding area was estimated at $640 million, the restored area of South Cape May suffered virtually no damage. In fact, a June 2014 Conservancy analysis of the restoration’s response to Hurricane Sandy showed a clear pattern of lower insurance claims related to flooding. According to the report, “Lower Cape May Meadows Ecological Restoration: Analysis of Economic and Social Benefits,” before restoration flood claims in Cape May Point following major storm events averaged $143,713. That number has now dropped to $3,713, leading to a projected flood claims savings of $9.6 million dollars over the next 50 years.

In short, says Zito-Livingston, “Cape May was already a special place for the migratory birds, and the restored habitats. But it’s good to see the preserve getting new life in the vocabulary of coastal resilience. Sandy showed that healthy wetlands and dunes are much more than beautiful. They provide many values, and one of their most important benefits can be the protection they provide for coastal communities like South Cape May, and the people who live here.”

Nothing Succeeds like Success

In the five years since Sandy, Conservancy scientists and others have increasingly turned their attention to quantifying the risk reduction benefits healthy habitats can provide. In Cape May, the economic value of the preserve and neighboring public lands is well known. Birders traveling to this part of the Jersey Shore—especially during Spring and Fall migrations—help extend the season in this beach town into November, long past summer’s traditional end on Labor Day.

But, until recently, making the case for the risk reduction value of restored or protected habitats—coastal wetlands, marshes, sand dunes, forests—has not been as clear or as quantified.

“Yes,” says Eric Schrading, field supervisor for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service New Jersey field office, whose agency provided technical assistance to Army Corps during the Lower Cape May Meadows Restoration, “There’s now a lot more acceptance of the value of things like living shorelines, marshes, dunes beyond their obvious and important value as habitat for plants and animals. People ask, ‘well, if we put in a living shoreline is it really as good as a bulkhead?’ And now more and more we have direct examples—like South Cape May—where we can say, ‘Yeah, it [habitat] actually is better.’ Not only for protecting people and property, but also for the creatures that our agency and The Nature Conservancy care about as well.”

The science supporting using nature to defend against storms and sea level rise continues to mount and, encouragingly, the engineering and insurance sectors are increasingly considering so-called “natural infrastructure” – like the managed freshwater wetlands and the dunes at South Cape May – in their risk reduction recommendations and products.

Most recently, a peer-reviewed paper by Conservancy scientist Mike Beck and colleagues from the engineering and insurance sectors showed that coastal wetlands prevented more than $625 Million (U.S.) in direct property damages during Hurricane Sandy. According to the study, published in Science Reports, New Jersey’s coastal wetlands alone accounted for $425M of the savings.

A Kind of Spokesmodel for Nature’s Defenses

Still, as persuasive as the science is, there’s nothing quite like seeing something for yourself. And since Sandy, the South Cape May Meadows Preserve has perhaps done more to promote and prove the effectiveness of nature’s defenses against nature’s strength than any other place.

“It’s great,” notes Zito-Livingston, “to be able to say this project was successful. Through interagency partnerships, this is a nice model for other places that want to look at how to use their natural assets to help defend their coasts.”

Join the Discussion