This story is part of a series designed to introduce the perspectives of alumni from the National Geographic Society and The Nature Conservancy’s global youth externship program. Each guest author is an emerging leader in conservation and storytelling.

The morning dew fogs my windscreen as I drive down the highway, and the wind whistles as it wraps and swirls over the bright blue kayak tied to the roof of my car. My hands grip the wheel tightly as I turn my head and peer through my side window, checking to see if my paddles are still attached.

I left home long before sunrise and am now driving north-east into the misty, grey-hued silhouettes of the Victorian Yarra Ranges. I pull over in the town of Warburton, park on the banks of the Yarra River and carry my kayak down to the water’s edge. The surface is deceptively still. Stomach full of butterflies and legs freezing in the cold water, I push off with my paddle and begin my journey.

I am on a mission to investigate if Melbourne’s freshwater ecosystems, and the platypus that inhabit these waterways, can survive amidst the spread of urbanisation. As the quality of the Yarra River catchment declines due to threats such as land clearing and stormwater, platypus are being forced to migrate further upstream or face extinction. Today I’m traveling that same journey in reverse, from the Yarra’s source to the sea.

The Yarra River

When most Australians think of the Yarra, they imagine a muddy-coloured river that sways and cuts through Melbourne’s city suburbs. But the river’s source lies far to the northeast, where I launched my kayak, and it flows for more than 240 kilometres all the way down to the mouth of Port Phillip Bay. This iconic river is more important than most people realise. The Yarra River catchment supports more than one-third of all Victoria’s native plants and animal species, including the platypus.

It also provides 70% of Melbourne’s drinking water, and 30% of Victorian’s population lives in the Yarra River catchment. To indigenous Aboriginal communities, this river holds great spiritual and cultural significance, a place central to their livelihood, culture, and identity. The Wurundjeri people know the river as the “Birrurung,” which translates to River of Mists.

Become An Extern

Join hundreds of global youth who are connecting with the National Geographic Society and The Nature Conservancy.

I’m undertaking this journey as part of an externship program, funded by The Nature Conservancy and the National Geographic Society. We were tasked to research an issue impacting our local freshwater ecosystems which led me to wonder: what’s happening to the platypus? The platypus is one of the worlds most seclusive and solitary animals, active mostly at night and rarely seen or photographed. Because of this, many Australians are not aware of the challenges platypuses face in urban environments.

As the sun rises over the valley, the Jurassic-like beauty of the surrounding forest begins to come alive. A sense of calm comes over me as my bright blue kayak slices through the cool water, swaying in tune to the current.

Watching the water’s surface, I suddenly start to see a string of bubbles appear. Plop, plop, plop…and then nothing. My kayak glides closer, my eyes lock, my thoughts quiet and breathing slows. A fluffy figure with a big, long beak and broad, flat tail pops to the surface. A platypus!

Platypus Under Threat

Despite their status as an iconic Australian animal, platypus populations are facing extreme challenges which threatens their survival. Platypus numbers have drastically declined since European settlement across Australia and are steadily declining in the Yarra River catchment.

A study conducted by University of New South Wales found that, over the past 30 years, the area occupied by platypus has shrunk by at least 22%, or about 200,000 square kilometers, which is an area the size of the entire state of Nebraska. In the last 10 years alone, 41.4% of sub-catchments no longer have records of platypus. This threat will only increase with population growth.

The platypus family (Ornithorhynichidae) are estimated to have lived here in Victoria for the last 120 million years, yet now their survival has come into question. The International Union for Conservation of Nature recognises the platypus as a Near Threatened species. Their status varies in different Australian states: in South Australia they’re considered Endangered, and here in Victoria they were listed as Vulnerable in 2021.

Sitting in my kayak, I watch as the platypus propels itself forward through the water using its short, webbed limbs. Watching a wild platypus forage is something that not many Australians experience, and it’s such a privilege. However, my joy is overshadowed by the knowledge that platypus face an uncertain future in this river if nothing is done to help them.

But the question remains: What is causing their numbers to decline? How exactly is urbanisation impacting the platypus and their habitat? The answer to those questions lies further downstream.

Why Riparian Vegetation Matters for Platypus

Riparian vegetation, the plants and trees that grow on the banks of the river’s edge, are very important for freshwater ecosystems. It helps to stabilise banks from erosion, filter sediments, retain soil nutrients, improve overall water quality and reduce the velocity of surface water runoff into the streams.

It also offers a great habitat for platypus, who dig their burrows into these very banks. They give birth and raise their young, also known as puggles, for up to four months in these temperature-controlled burrows and need overhanging vegetation as protection.

As I travel further and further downstream, I can’t help but notice a decrease in the amount and quality of vegetation on the Yarra’s banks. Earlier this morning I was enveloped by large trees and brightly coloured bushes, the air tinged with the scent of eucalyptus. After a few hours of paddling, I’m now surrounded by grass fields and agricultural pastures.

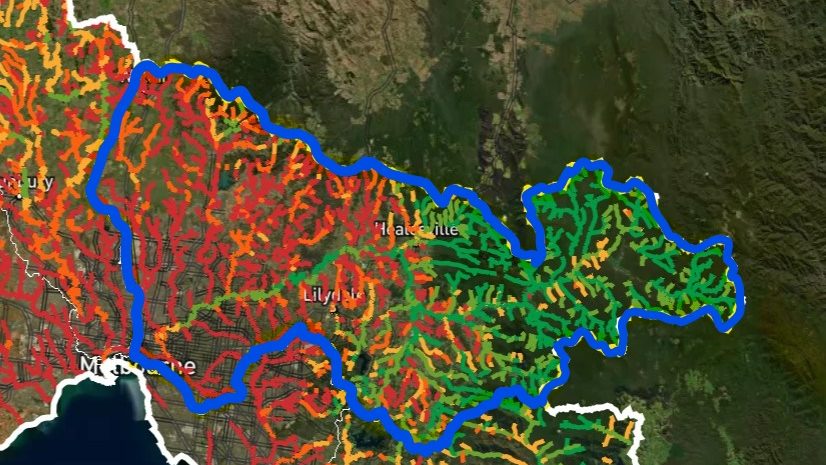

This type of clearing is typical in peri-urban environments. In less than 200 years since European settlement, Victoria has destroyed more than half of its native vegetation. A 2018 study found that the quality of vegetation in the Yarra River catchment is poorly conditioned closer to urban regions, and that this decline is spreading outwards from the city and into regional areas.

Without native riparian vegetation, river banks become degraded and weak, which hinders a platypus’s ability to create burrows and raise young. To combat this erosion, we install urban solutions such as concrete slabs and rock boulders, which only make things worse. That same study found that 48% of the Yarra catchment’s waterways are considered ‘very poor’ habitat conditions for platypus.

Stormwater And Starvation

After many hours of paddling, passing different creeks and adjoining rivers, I’m now about 10 kilometers away from Melbourne’s CBD. The once-clear water has changed into an ominous brown hue. A plastic bottle wrapped in blue passes me on my left, my brain skips a beat thinking it had come from my kayak.

The sounds of birds and wildlife are replaced by the disruptive noise of industry. Cars and trucks fly over me as I paddle through an underpass, and the sounds of construction vibrates the air. Concrete lays where trees stood, and what was once wild is now governed by man. Similar to the loss of riparian vegetation, these impervious surfaces are also a problem for platypus.

In natural environments, rainwater soaks into the soil and is absorbed by the vegetation, recharging the groundwater and slowly releasing it back into our waterways. But in urban environments, our houses, buildings, and roads replace forests and wetlands. These impervious surfaces collect, direct, and dump large volumes of water straight into our rivers and creeks, creating large flash flood events. Even light rain can massively increase the frequency and magnitude of these stormwater flood events, producing unnatural flow regimes that greatly impact freshwater ecosystems.

These floods are extremely problematic for platypus. Platypus swim and hunt underwater with their eyes closed, sealed off by specialised skin flaps. To find their food, platypus use fine-tuned receptors in their bill to map their surroundings by detecting electrical impulses in the water which are generated by the muscle contractions of their prey, macroinvertebrates. This allows the platypus to locate its prey even in the darkest and murkiest of waters.

But in urban environments, these macroinvertebrates get swept away in unnatural flood events, starving platypus of their main food source. Stormwater is also responsible for further deteriorating river banks, fragmenting populations, and can flood and destroy platypus burrows.

Platypus play a vital role in freshwater ecosystems as a keystone apex predator, ensuring to keep the ecological food chain in balance. If there are no macroinvertebrates or healthy vegetated banks then the platypus is forced to retreat upstream to escape the disruptive conditions or die. If this happens, whole ecosystems will crash and fall out of equilibrium, something that will continue as Melbourne expands its urban footprint into platypus habitat.

Sadly, this is already a reality. In the 1950’s, Melbourne residents could find platypus within 5 kilometers of the city centre. Today, you’d have to travel more than 15 kilometers to have a chance at spotting one.

In 2021, a Victoria-wide platypus eDNA survey found that the Yarra River catchment showed a clear gradient of decline in platypus numbers towards the lower reaches that are more urbanized. Research by CESAR found that when compared to historical data, the Yarra River has experienced a 38% decrease in the length of waterways estimated to be occupied by platypus.

How You Can Help Platypuses

Everything in nature is connected, and like the platypus we are part of freshwater ecosystems. Australians can participate in citizen science opportunities such as reporting platypus sightings, which help scientists and academics better understand platypus population sizes, distributions, and threats. Some popular sites include:

- CESAR: platypusSPOT

- Australian Conservation Foundation: The Platy Project

- iNaturalistAU: Platypus Conservation Initiative

- Atlas of Living Australia

You can also join community groups and council-run programs to help plant native vegetation along the river banks. Install rain gardens into your back garden which help to capture, filter and distribute stormwater into the soil rather than into our drainage system. Smart Water tanks are also a great way to help capture rainwater, reducing the amount of stormwater that goes into our catchment, while conserving water and even lowering the water bills.

Platypuses are also highly susceptible to litter and rubbish in our waterways as it can easily get caught around their bills. In Melbourne, platypus are up to eight times more likely to become tangled in litter than those in regional Victoria. In 2019, a young female platypus had to be put down after becoming entangled in three elastic bands. Before you throw away your trash, make sure to cut items that have loops or rings up to 25cm in circumference, such as hair ties, face masks, and fishing lines.

If you live outside of Australia, then sadly you won’t have any platypuses swimming in your local rivers. But do not assume that this conservation issue is isolated. The story of the platypus and Melbourne’s expanding urbanisation is a microcosm of what is happening all around the world.

For example, the Florida manatee is facing extinction due to excessive nutrients washing into the rivers from urban stormwater, agricultural runoff and wastewater, causing dangerous algal blooms that kill their main source of food, seagrass. In Kerala, India, urban expansion has led to severe pollution, degrading wetland habitats and reducing the abundance of fish. This has negatively impacted local kingfisher populations, resulting in a decline of kingfisher species that are native to the area and rely on these wetlands for migration.

No matter where you live, what happens on land flows down into our freshwater ecosystems and impacts our wildlife.

At the end of my journey, the river has changed from beautiful and wild to more familiar. I finish my paddle in Melbourne’s CBD, surrounded by high skyrises, floating bars, and thousands of commuters, all busy and bustling, a sensory overload. My bright blue kayak no longer feels foreign to the environment. I’m careful not to get distracted and fall into the water, as this section of the river is illegal to swim in due to high pollution levels.

My hope is that our iconic platypus can not only survive but thrive in all parts of the Yarra River catchment. By restoring and preserving the entire river system, we can ensure a sustainable future where both humans and wildlife can coexist.

I encourage everyone to go outside and explore nature, who knows, maybe you too may discover something interesting about your native wildlife.

Discover the conservation work of other externs from Colombia, the Maldives, and the United States in Nature Conservancy Magazine.

Excellent article. Thank you for taking us on your adventure, Brendan!