A young Black woman stands knee-deep in the salt marsh, bent over, intent, staring at a container she holds in her hands. She’s so focused she doesn’t notice the white couple strolling by a trail along the estuary.

They, however, notice her.

The couple begin shouting. “Hey, what are you doing? We’re calling the cops!”

The young woman in the marsh is Dr. Tiara Moore, who is collecting samples to analyze for environmental DNA (or eDNA), to detect species present and how they were being affected by threats like algal blooms.

Moore, no stranger to this situation, calmly explained her research, her career as a marine biologist and exactly why she was standing in a marsh with small containers. The couple, hopefully chastened, began a conversation. They took the photo of Moore in the field that leads this blog.

Using eDNA to assesss biodiversity has been an important strand of Moore’s career, taking her from marine environments to Pacific Northwest forest. It’s fascinating science that can help shape conservation actions. But that story also can’t be separated from another strand: that of Moore feeling unwelcome, of being the only Black person in the room, of facing the barriers of systemic racism.

From Ocean to Forest

Moore started her college career with the intent of becoming a pediatrician, a story she tells in an excellent series of interviews with Washington Nature. An enrollment in a tropical biology class changed that trajectory. She admits she took it mainly for the class field trip to Costa Rica. There, collecting water samples, it became clear what she wanted to do with her professional life.

Through her master’s and Ph.D. work, she continued collecting those samples. It was when she started her Ph.D. work in 2015 that she saw the potential of eDNA monitoring. “I was really in that first set of scientists trained in using eDNA at UCLA,” says Moore. “I immediately saw its potential as an innovative tool for biodiversity monitoring.”

eDNA is, simply, DNA left behind by an organism in the environment. “Everybody likes crime shows,” says Moore. “In those shows, the detectives might be taking a sample from where a criminal touched a door. They’re looking for the criminal’s DNA. Animals leave behind DNA, too.”

This can be in feces, hair, shed skin, pollen. “Animals leave behind these traces, and all of it contains DNA,” says Moore. “You can capture that through soil samples and even capture it in the air. You take that sample and then you analyze it for genetic codes. You run those codes through a database, matching your samples to species.”

Traditionally, monitoring wildlife of any kind – whether large mammal or fish or insect – required some form of observation. You might do transects searching for the creatures, or set traps, or search for scat. It could be a long, painstaking process, and you might well miss an elusive or small or rare creature. Microbes and fungi might never be accounted for at all.

Moore saw the potential for eDNA in the marine environment she considered her professional home. Taking water samples and sediment, she could monitor the presence and absence of diverse marine life found in the study area. She was specifically monitoring how nutrient pollution and associated algal blooms in southern California, using eDNA to identify bacteria responsible for algal decomposition and water quality impacts.

While attending a marine science conference, she struck up a conversation with Dr. Phil Levin, lead scientist for The Nature Conservancy in Washington. As she described her work with estuarine sediments, Levin wondered aloud: Could she bring eDNA to a Washington forest?

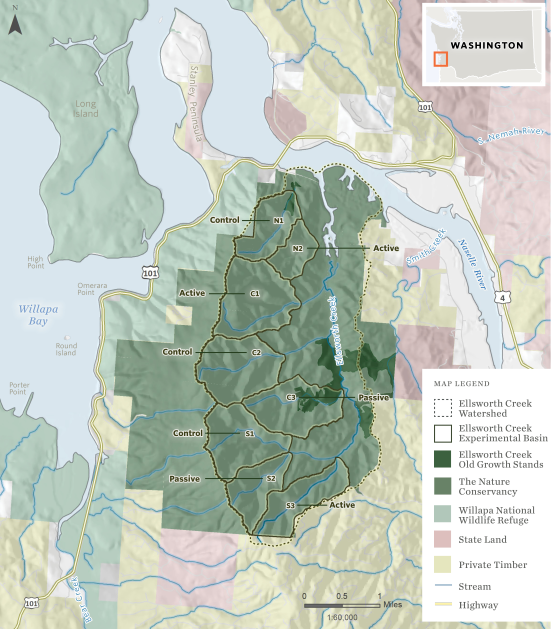

And that’s how Moore, a marine scientist, brought her DNA work to the Ellsworth Creek Preserve in western Washington.

Seeing the Forest for the eDNA

Ellsworth Creek Preserve has been a bold conservation experiment since 2000, when the Conservancy purchased the entire 7,600-acre Ellsworth Creek watershed. More than 4,000 acres of the acquired property had been logged, so it was not a pristine preserve. This marked a bit of a conservation departure, as the Conservancy often specialized in buying small preserves to protect existing biodiversity.

The ongoing restoration effort has tested a variety of treatments, including allowing the forest to regrow without intervention and more active approaches including selective thinning and prescribed fire. The forest has reclaimed areas that were once logging roads and clearcuts. But how has the benefited biodiversity? What treatments are working best.

Enter Moore’s eDNA work. “I don’t have to spend hours in the field with binoculars or camera traps,” says Moore. “Even if I did that, I would only see the animals that walked by.”

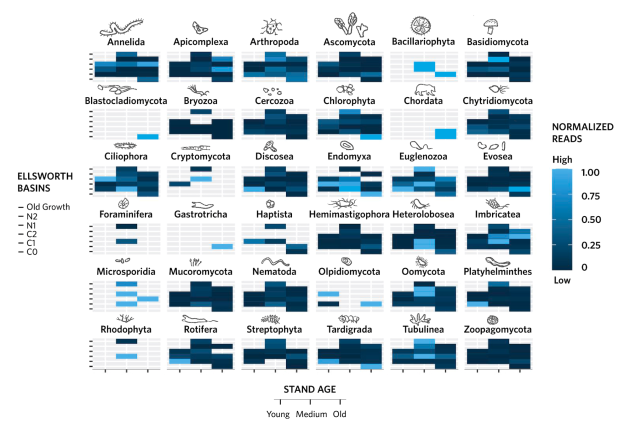

By collecting eDNA samples, she found evidence of more than 800 species at Ellsworth Creek Preserve. Many of them were microbes or fungi, but she also found evidence of creatures as large as wolves. (She frequently likes to state, with a laugh, that there was no evidence of Bigfoot).

“You get a big picture from a small scoop of dirt,” she says.

She was looking for the presence and absence of species, assessing them against forest management treatments and other factors. The team recorded the environmental conditions where samples were taken, including tree measurements, soil type and hill slope.

“We were looking for what the drivers are of biodiversity presence and absence,” Moore says. “Then staff can use this to inform management practices. It can shape future restoration efforts to focus on those activities that could achieve the most for biodiversity.”

“You Can Be in This Space”

In our conversation, Moore expresses delight that her eDNA work can shape effective forest conservation. “I set out to see if this could work in a completely different ecosystem,” she says.

And she was thrilled to find the stories told in those soil samples, and how they can continue to shape the conservation story at Ellsworth Creek. But she also admits she felt another pull.

“When I moved to do a postdoc in the forest, I knew I had to find a way back to marine science,” she says.

And she wanted something else: to help other Black marine scientists find their way.

Throughout her career, Moore has often found herself as the only Black person in the room, whether in a university lab, a professional conference or a large conservation organization. She frequently felt unwelcome.

Boarding a diving boat, she was asked by other researchers if she could swim. People would ask if she was along to carry the SCUBA tanks.

She’s also aware of the historical trauma. She notes surveys that have found that fewer than half of Black people in America can swim, a legacy of a time when going to the pool could bring danger. Many public pools, particularly in the southern United States, were off-limits. White people sometimes dumped acid in Black-designated pools, making swimming always a risk. This trauma in turn feeds stereotypes that Black people can’t swim, that they can’t be marine scientists.

And even collecting samples for her eDNA work can lead to people threatening to the call the police.

She tells me that even in seemingly well-meaning organizations, bias and systemic racism come into play. There are the diversity messages and trainings, but still a resistance to real change. “I often feel tokenized and not valued for my work,” she says.

She wondered: where are the other Black marine scientists? That led her to social media, modeling a Black in Marine Science campaign after the popular Black Birders Week. She wasn’t alone. But she found many others, like her, who felt alone in this professional space.

This in turn led to her launching a nonprofit called Black in Marine Science. Running this organization became her full-time job with the Conservancy. This spring, she became the organization’s first CEO.

“I want Black marine scientists to know, you can be in this space,” says Moore. “We can share experiences, discuss barriers, and empower each other. We can talk about how to deal with our hair during dives.”

Moore’s goals include a research facility, called BIMS Institute, located in a predominantly Black community, with research focused in that area to see impacts of water quality and climate change. She’ll continue the use of eDNA and she’ll continue to inspire the next generation of marine scientists. “I found my way back to marine science,” she says. “And I found a community of others who have shared my life experiences. That keeps me going. That keeps us going.”

Join the Discussion

1 comment