I’m on a quest to catch a fish in each of the 50 U.S. states – and to use each adventure as a way to explore conservation, the latest fisheries research and our complicated connections to the natural world.

Whenever I speak, whether it’s to a small college class or full auditorium, I can always count on one question: What gives you hope?

It’s a good question, but I always find it unsettling – because the conservationists asking it honestly don’t know where to go for hope anymore.

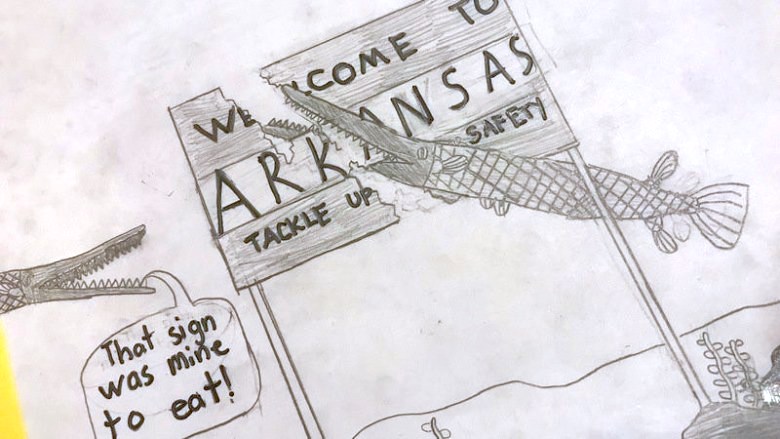

The next time I get this question, I’m pointing them to Henry Foster, an 11-year-old kid who draws fish cartoons and has already led a successful effort to have Arkansas designate a state primitive fish. And the new state fish was one that for most of the past century was considered “trash” and was openly persecuted.

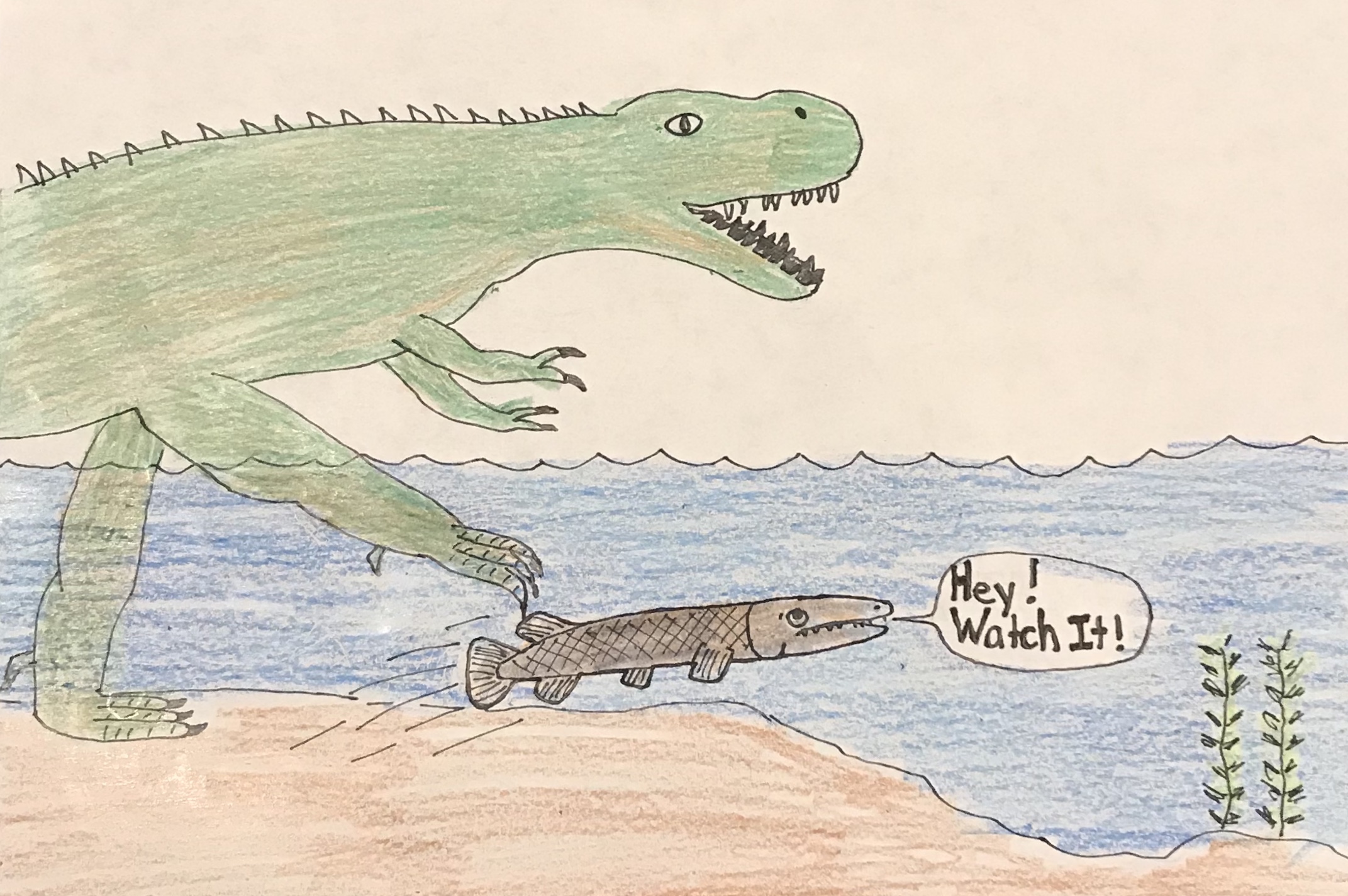

For Henry, alligator gar are the coolest fish that swims. It’s not always an easy path to get others to share that view.

Game Fish and Trash Fish

When you mention fishing in Arkansas, many fly fishers will assume you’re going for trout. This despite the fact that trout are not native to Arkansas.

I actually fished Arkansas’s White River for trout nearly twenty years ago. The White is considered a destination river, with plentiful and large trout. The North American record brown trout was caught there.

I struggled. And then an angler directed me to fish by the PVC pipes that ran into the river. I had seen these pipes snaking down from the parking lot.

“That’s how they stock the trout,” the angler said. “They don’t want to walk them down to the water, so they just put the trout from the truck into those tubes and they slide right into the river. So the key is to fish right by those tubes. It’s best right after they stock, but a lot of the fish stick right around there.”

This advice kind of ruined the aesthetic, but I’ve come to realize that little tip tells a lot about the state of freshwater fishing in North America. A few select “game” species have been stocked willy-nilly across the continent (and around the world). It’s not natural, but unfortunately many anglers don’t seem to mind.

On the flip side, those same anglers deride interesting native species as “trash,” fish to be thrown on the bank and left to die. Changing attitudes about our native fish has been an ongoing crusade of mine, but old attitudes die hard.

Trout are revered in Arkansas. Alligator gar? Not so much. At least throughout much of the state’s history. For decades they were shot and dynamited. In the tourism brochures, it’s still all about trout. But when I returned to Arkansas for a conference this summer, I didn’t want to stand by a PVC pipe. I wanted to see an alligator gar.

Muddy Waters

You will still find plenty of people who think the only appropriate way to deal with alligator gar is to shoot them, but there is growing subculture who loves the fish. One of the leaders is Mark Spitzer, a University of Central Arkansas creative writing professor, novelist, poet, essayist and angler. He’s written numerous books on his passion for “monster fish,” including two devoted exclusively to gar.

“More than any other fish, gar are prepared to fight on, adapt away, and crawl from the muck again,” Spitzer writes in Season of the Gar.

When we learned we both would be attending the Outdoor Writers Association of America conference in Little Rock, we immediately made plans to sneak out for a few hours of gar fishing. Unfortunately, heavy rains rendered the rivers high and muddy.

But we headed out and set up large rods along a backwater of the Arkansas River. It didn’t really matter that we didn’t have much time, and that the fishing conditions didn’t look promising. We were two like-minded anglers talking fish and conservation and the future.

Spitzer acknowledged that much of the attention in his state still went towards trout or bass. But he saw changes. At one point, people just shot gar. They were pretty much wiped out of the Arkansas River.

“We’re a culture that waits for a problem to get really bad before we do something about it,” he said. “Then we take drastic measures.”

In the case of the alligator gar, there were reintroductions and harvest restrictions. The Arkansas Game and Fish Commission had done a good job managing the species rather than just allowing uncontrolled killing. Spitzer and others participated as angling citizen-scientists supplying data for the gar they caught. River conditions, including bountiful prey fish, seemed to bode well for the alligator gar’s future.

I caught a channel catfish, but we didn’t have any gar encounters that morning. For me, just knowing they were there was enough. But despite Spitzer’s seeming optimism, I wondered if we could really make a difference for native fish.

After all, a quick look at most fishing social media or fishing magazines will reveal countless anglers tossing native “trash” fish on banks or shooting them with arrows. And they’re proud of it, as if they are performing a public service by killing gar, suckers and buffalo.

I pondered aloud whether there is any hope of changing anglers’ and others’ minds, or if we were deluding ourselves.

“Have you heard of Henry Foster?” Spitzer asked.

The Garkansas Campaign

I had heard of Henry, and his campaign to make alligator gar the state fish of Arkansas. I knew it was time to talk to him, and so I arranged a call with him and his mother, Melissa Foster.

Henry loved fish from an early age, carrying Nemo toys in each hand. At age six, he saw gar in an aquarium and immediately thought they were the coolest creatures he had seen. And at age ten, he knew what he wanted to do.

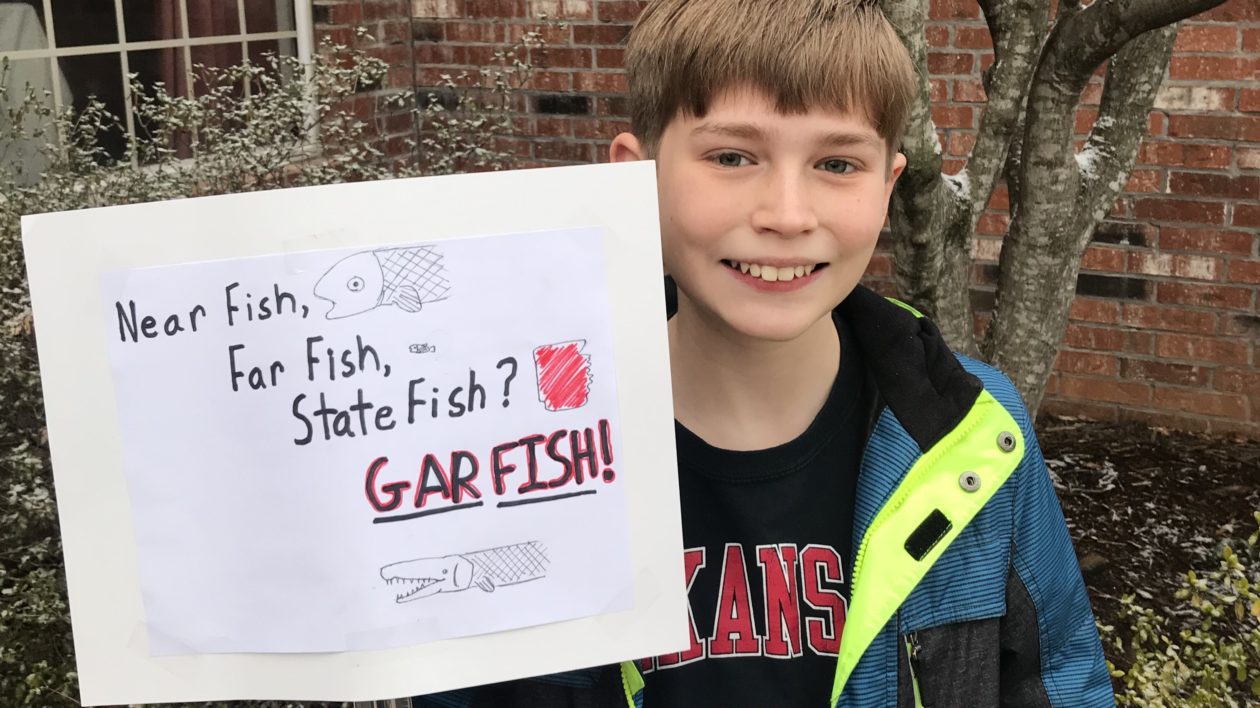

“I figured out that Arkansas had no state fish,” he says. “I didn’t want it to be a fish that another state had, and I didn’t want it to be a non-native fish.”

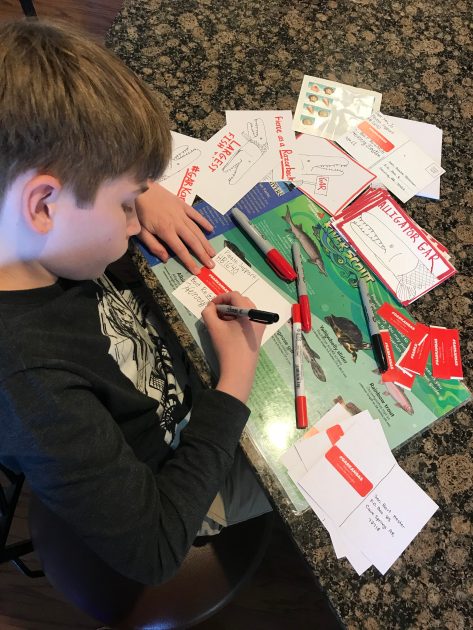

While Melissa notes that the Fosters are not a political family, Henry quickly jumped into the task with a fervor. He reached out to the ultimate garficionado and researcher (and frequent Cool Green Science star) Solomon David for advice and inspiration. “Dr. Solomon David made sure every fact I used was correct,” he said. “I wanted everything to be correct. I knew it had to be.”

Henry launched a #Garkansas social media campaign. He spoke to media outlets. He set up a booth at the local farmers’ market. He spoke at a school assembly. He drew “gartoons.” For every audience, he tailored the message – a lesson even many of the most seasoned scientists have never learned.

While Henry does fish, he has never fished for gar. He’s motivated because he thinks they’re cool animals and because he loves streams. “Any time Henry sees a body of water, he’s trying to figure out everything about the ecosystem,” says Melissa.

For his campaign, he also had to figure out the political process. He spent time gathering support and studying everything related to alligator gar. Then it was time to bring it to the legislature.

On the day it came before the Arkansas House, the bill’s sponsor (the appropriately named Rep. Denise Garner) was ill. Henry had to make his case directly. He spoke with passion and built his case, by all accounts doing a masterful job. It seemed a slam dunk.

Except for the game fish boosters. “The trout people, the bass people, the catfish people all started making their cases,” Henry said. “I kept thinking over and over, ‘it’s not going to pass, it’s not going to pass.’”

News coverage of the event (and the associated comments) reports on the pushback to Henry’s crusade. One representative reported that her local chamber of commerce spends thousands of dollars to bring in anglers. For trout.

“It was really frustrating that people kept bringing up that the North American record brown trout was caught in Arkansas,” says Henry. “Brown trout aren’t native here.”

Another representative stated he just didn’t like gar. This was echoed in many newspaper comments.

But Henry was prepared, and the alligator gar won the day. It made it through the House, Senate and to the Governor’s office. It became the “Arkansas state primitive fish,” which some saw an unnecessary distinction, but Henry sees it as a worthy title.

“It’s the first state primitive fish,” he says. “Maybe other states can follow.”

And he’s not done. “In the future, I’d like to see less trout stocking and more gar returned to their native waters,” he says. “I think this will eventually be my career.”

And he has a message for all of us fighting for freshwater fish and conservation: Don’t despair. Trying to change perceptions of freshwater fish, and fishing, at times seems like fighting the strongest current. But kids like Henry can urge us forward, reminding us what’s important.

“Persevere and keep at it, even when things get tough,” he says. “I could have just quit when I was writing all those letters, when I was sitting in the cold at the farmer’s market. Just keep at it. It’s for the fish. Do it for the fish.”

Thank you! Fabulous article that brought tears to my eyes. With all the incredible ignorance and violence of our species, we are blessed with the great Henry to give us hope. Bravo!

What an amazing young conservationist is Henry. More power to him and all those like him. They are so desparately needed. I live in trout heaven (Canada) but gave up fishing pretty much before I started. Have never been to Arkansas or seen a Garfish but am delighted with this win for the natural world. Hope is in short supply in so many places. Grateful to you both for providing some of that.

Henry Power!!

No ordinary fish … but a truly extraordinary young human being! Glad they’re both on the planet.

Its so sad that so many fishermen these day follow the stocking trucks. Is this really what sport fishing has come to? And too, as far as trash fish goes, here in Wyoming, Rainbow Trout are at the head of my list with Brook Trout a close second. Saving the native Cutthroat Trout is a priority. Fortunately, this mindset is beginning to take hold.

Man, did I need to read this. Late July afternoon, working at the dining room table, floor fan cooling my feet (102 degrees outside), and feeling pretty darn gloomy about nearly everything, I’m one of those “What gives you hope?” people. Thanks, Henry. Words to live by: “Persevere and keep at it, even when things get tough,” he says. “I could have just quit when I was writing all those letters, when I was sitting in the cold at the farmer’s market. Just keep at it. It’s for the fish. Do it for the fish.”