I have a confession: I’m becoming a bit obsessed with mammal-watching.

My path to becoming a naturalist started with birds, and winged things will always be my first taxonomic love. But after years spent working alongside countless ecologists and mammal nerds, I started dabbling in mammal-watching. And now I’m hooked.

It helps that I moved to Australia 5 years ago, and this continent’s mammalian wonders still astonish me at every turn. To listen to a koala grunting in my backyard or watch kangaroos sunning in an empty field is a constant source of joy.

But there is so much more to the world of Australian mammals. There are dibblers and fat-tailed dunnarts, tiny honey possums and chonky quolls, kangaroos that live in trees, and marsupial moles that swim beneath the desert sands. And not far away, across the islands of the south-west Pacific, you can find some of the world’s rarest and least-known species, like giant rats and flying foxes galore.

So whether you’re a seasoned wildlife biologist or a newbie mammal-watcher, you need these two guides to mammals of Australia and the southwest Pacific.

And for more great reads from this region, check out my review of a new Australian bird guide, a page-turner on platypus, and a romp through the history of Australian naturalists.

Top 10 List

-

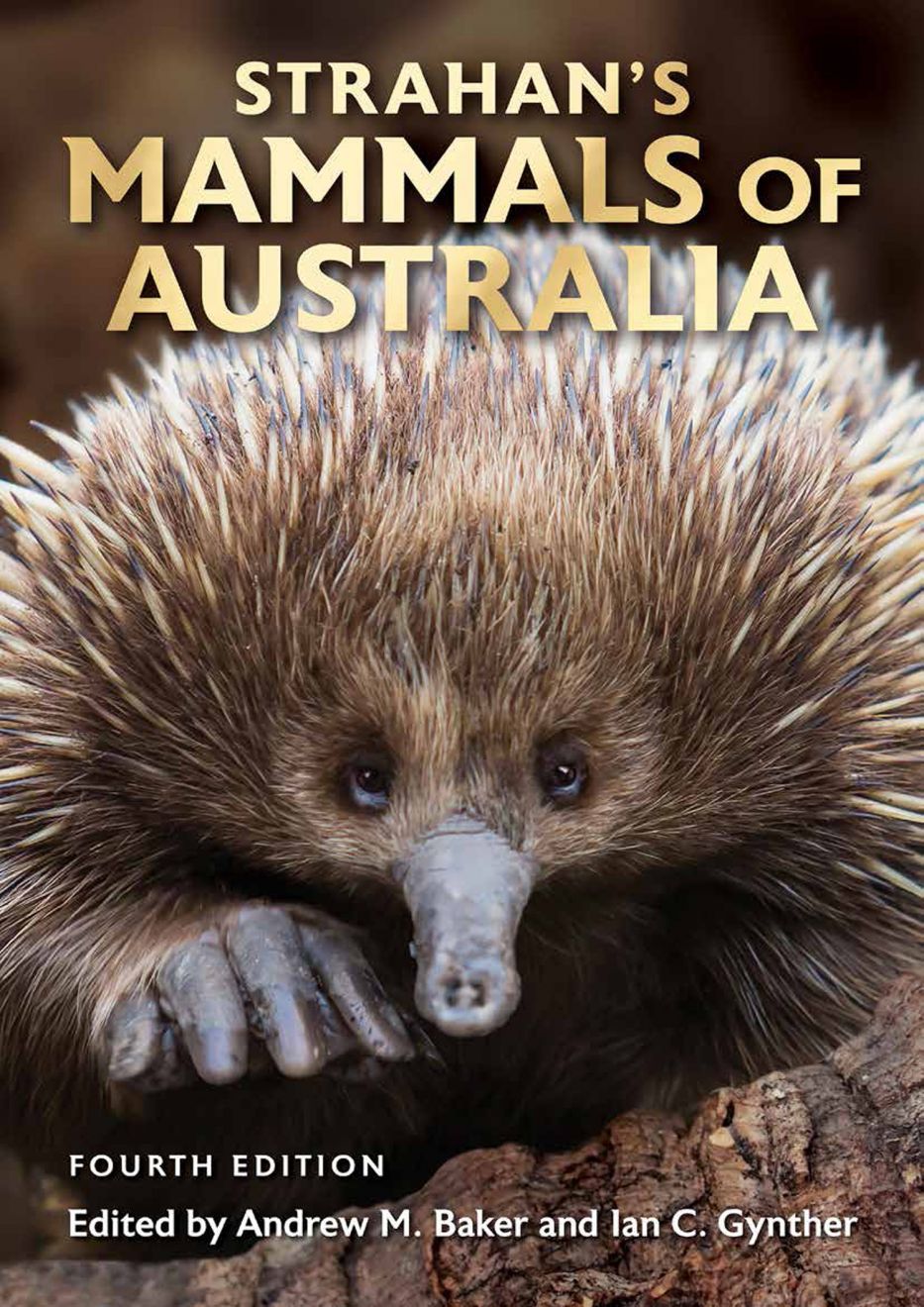

Strahan’s Mammals of Australia, Fourth Edition

Edited by Andrew M. Baker & Ian C. Gynther

This fabulous desk reference is the ultimate guide to Australia’s mammals. At 838 pages, it’s an absolute monster of a book, and worth every penny.

Mammal nerds will notice that this new edition has a slightly different title than previous versions, which were published under the title “The Mammals of Australia.” The fourth edition incorporates a slight title change to honor the book’s original first author, the late Ronald Strahan.

The book includes detailed accounts of all 381 species of native mammal known to have existed in Australia (and its offshore waters) since European settlement, plus accounts for the 23 introduced species that have self-sustaining wild populations.

Much has happened in the world of Australian mammalogy in the 15 years since this book was last updated. The fourth edition includes 14 newly described species and incorporates changes to taxonomy and species names (both common and scientific).

A small detail that I appreciate: the inclusion of a pronunciation guide and translation for all scientific names. Where else would I learn that the Nullarbor barred bandicoot’s scientific name, Perameles papillon, translates to “butterfly pouched-badger”?

Each species account includes a detailed description of the animal’s biology and behavior, color photographs, and range maps showing the current and former extent. Some of Australia’s mammals are restricted to predator-free havens — either fenced reserves or offshore islands — and the range maps neatly incorporate this detail via color-coding.

A quick-reference box alongside each species account includes technical details, like the animal’s size and weight range, key identification features, alternate names (both scientific and indigenous), conservation status, and subspecies.

The more than 1,500 color photos included throughout are fabulous, showing both key identifying features and fascinating elements of each species’ behavior. Particular highlights include a photo of a southern marsupial mole (itjaritjari) sticking out its tongue, an eastern pebble-mouse carrying pebbles, and a narrow-nose planigale grooming its whiskers.

I’m particularly impressed by the editor’s attention to detail for the 34 species that have gone extinct since European settlement. (Two of which became extinct in the time since the previous edition.) A majority of these species were never photographed alive, so the editors include photographs of museum specimens and illustrations to give readers a sense of how these species appeared in life. Some of those illustrations are from historic sources, such as John Gould’s Mammals of Australia. But in other cases where no illustrations existed, the editors commissioned custom artwork drawn from museum specimens.

Perhaps what I enjoy most about this book is that — despite its heft and purpose as a desk reference for biologists and field naturalists — it’s readable and accessible for amateur mammal enthusiasts. It’s a fantastic resource for anyone who wants to venture beyond kangaroos and koalas and dive into Australia’s marvelous mammalian fauna.

Available from New Holland Publishers.

-

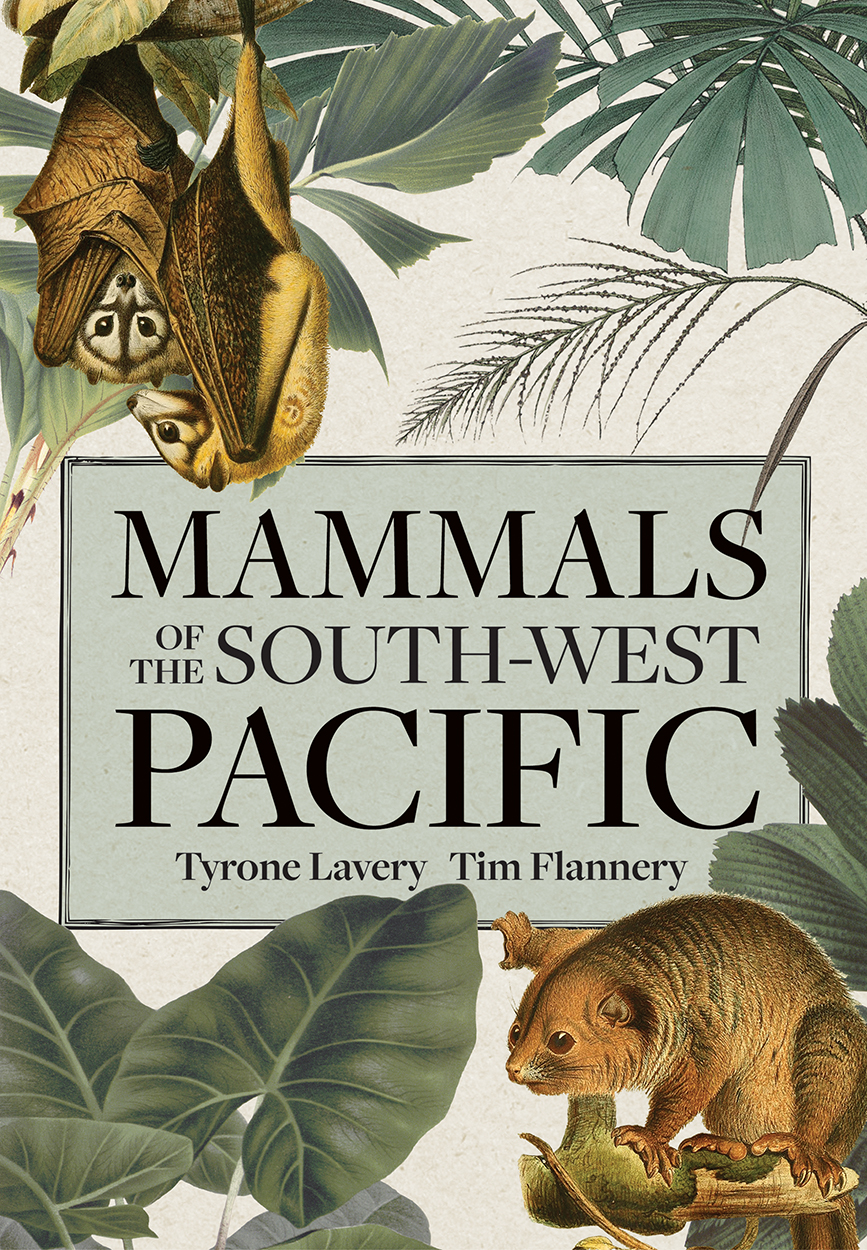

Mammals of the South-west Pacific

By Tyrone Lavery & Tim Flannery

Once your appetite for Australian mammals is satiated, head farther afield to the islands of the south-west Pacific.

This wonderful field guide covers the terrestrial mammals found on the islands within Melanesia, Micronesia and Polynesia. (Readers should note that while the book does include New Zealand, it does not cover mainland New Guinea or Australia and its offshore islands.)

The beginning of the book includes helpful summaries of the region’s geological history, flora and vegetation, paleontology, zoogeography, and conservation. Authors Tyrone Lavery and Tim Flannery, who both have extensive first-hand knowledge of the mammals in this region, also summarize the long history of human translocation of mammals between islands, with implications for current distributions.

The species accounts cover more than 180 terrestrial mammals (including bats) found across the 24 nations and territories included in the book’s geographic range. The detailed species descriptions are accompanied by color photographs and illustrations, along with range maps that indicate current distributions, local island-level extinctions, presumed extinctions (no verified records in the last 100 years) and presumed occurrences.

Perhaps most striking is how little we know about the mammals of this region. Many are only known to Western science from a handful of specimens, often collected more than 100 years ago. The species accounts describe extensive field surveys for a species that turn up nothing, only for a field biologist who happens to be in the right place at the right time to get a fleeting glance. Other species, like the Vangunu giant rat, were only just described in 2017. Lavery and Flannery have gathered all of these scattered records into a single, invaluable resource.

One of my favorite things about field guides is how they are so much more than simple identification tools. My colleague, Matt Miller, has written about how field guides “serve as invitations to adventures, as memories of days afield, [and] even as a source of solace when I can’t be outside.”

That’s especially true in a region like the south-west Pacific. I’m lucky enough to have traveled within Melanesia on several occasions, visiting some of the islands covered in this guide. The mammal-watching is exceptionally difficult: it requires considerable funds, assistance from local landowners, physical stamina, and many hours in the field.

And this is why Mammals of the South-west Pacific is such a wonderful resource. It brings to life the multitudes of mammals in this remote part of the world, most of which would remain off my radar without such an informative reference.

It’s unlikely that I’ll ever watch a black and white Waiego cuscus clamber through the treetops, or see a western long-beaked echidna snuffle through the leaf litter. But with a good field guide, a girl can dream. And with this field, guide, you can, too.

Available in Australia and New Zealand from CSIRO Publishing. Available elsewhere through CRC Press.

Join the Discussion