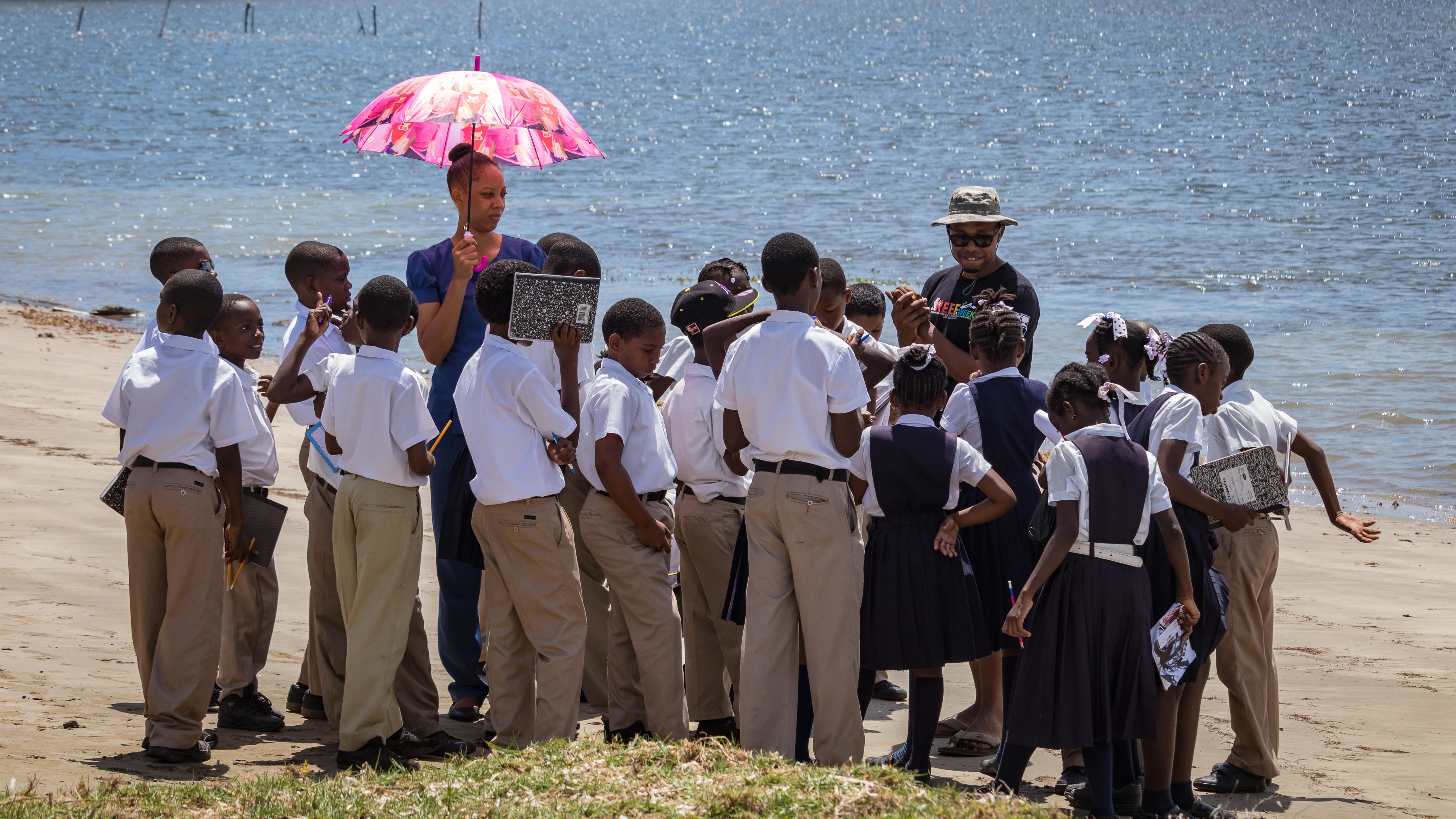

By the time we reach the seventh and last station on today’s field trip itinerary—the much-anticipated “Drone Demonstration” according to the sign outside the tent—the 30 or so fifth and sixth graders I’ve been following this Tuesday morning in March are still bright-eyed and curious despite the heat. Even after several hours on the beach, their colorful uniform shirts and pants are still clean.

I, on the other hand, am dirty, sweaty and wilting in the unrelenting Caribbean sun.

There’s not much shade here on Telescope Beach near Grenville on the windward side of Grenada. Of course, there’s not much beach either, which is the main reason we’re all here today for Reef Week—because the people of Grenville need their beach back, and as I’m discovering, these children, and the science they’re here to learn about, have important roles to play in achieving that long-term goal.

I stand off to the side, close to the teachers and parents serving as field trip chaperones, and listen as Steve Schill (who, like the kids, also looks bright-eyed and annoyingly unwilted) introduces himself as a scientist with the Conservancy’s Caribbean program.

I know he’s going to do a great presentation because I’ve just spent three days tagging along with him as he used drones to collect data along the beaches, reefs and mangroves across the north end of Grenada. But today, he and other Nature Conservancy (TNC) scientists and partners are putting their research aside to teach more than 750 students from schools all over the country about the importance of their island’s environment.

Who Wants to Be a Marine Biologist?

Schill starts his presentation with a question: “Anybody here want to be a marine biologist?”

I almost raise my hand. I mean, doesn’t everyone secretly want to be a marine biologist? Apparently not, because only a few hands go up. Schill is unfazed, and his smile says: “We’ll see about that.”

“Okay, then,” he says, “who wants to see some drones?” All the hands shoot up.

The students gather around a table covered in quad copters, submersible drones, computers, power strips, and other equipment that Schill and other scientists use for field research. Schill explains how the sleek machines work and also how scientists use these kinds of tools to collect data they need to understand and address one of the main problems that has changed Telescope Beach – the damage to the offshore coral from human impacts, storms and climate change.

Over the years, the reef that once thrived near Grenville has degraded from boat strikes, and from mining for limestone to make concrete. Eventually the reef could no longer shield the beach from waves, and the shoreline eroded as much as 500 feet. Now, the once-wide beach has been whittled down to the narrow strip we’re standing on today, but, as Schill tells the children, all is not necessarily lost.

“One of the first steps in getting the beach back,” Schill says, “is getting the reef and the mangroves back.”

Drones at the Water’s Edge

To do just that, the Conservancy in partnership with other NGOs and the government of Grenada launched a project called “At the Water’s Edge.”

As part of that work to get the beaches and the mangroves back and help improve the community’s resilience to storms and sea level rise, TNC and its partners, with help from local fishermen, also installed about 30 meters of artificial structure on the northern reef in Grenville Bay. The goal was to test whether or not these structures could help rebuild the damaged reef.

So a few days before Reef Week, Schill and his research partner, George Raber, used drones to help scientists survey the two-year-old underwater structures to see if the restoration was working the way scientists had planned. Were fish using the structures? Were corals coming back to help rebuild the reef and protect the shore?

Using submersible and aerial drones, as well as scientists with snorkels and digital cameras, Schill and Raber collected enough data to create 3D maps of the structures and found that the restoration is working. Fish are using the structures for forage and shelter, and corals are beginning to grow back on the substrate. The data tells a story of success, but the visual aspects of the science also help draw people in. It’s certainly working with the kids.

It’s one thing to hear that a project is working. It’s another thing entirely to see the data brought to life. Schill gestures to a video playing on the tent wall beside him and the students are mesmerized as he shows them the 3D models of the underwater structures and video of the ocean floor just offshore. Suddenly the screen shifts to aerial video from above the reef, and there, in the clear water, is an eagle ray. “A ray! A ray!” some of the kids call out.

They are clamoring with questions now. How do scientists use drones to solve problems? What other animals have they seen on the reefs, and have they seen sharks? How do underwater drones work? Are they going to fly a drone today?

Sure, Schill says, and the kids are out of the demonstration tent and onto the beach in a flash. They watch in awe as Raber launches a small, black quad copter and then quickly make a semi-circle around him so they can watch the live video feed from the drone as it flies along the beach and out over the waves and the reef.

They ask Raber if he can see any sharks, or rays. Not today, he says, but “we can take a drone selfie.”

A drone selfie? There’s such a thing as a drone selfie? Apparently there is. And the kids scream with excitement as the drone hovers above them and they can see themselves on the live feed. As they line up to move to the next station, Schill asks his question again. “Now, who wants to be a marine scientist?” This time, nearly all the hands shoot up.

The Change We Need Now

They file away chattering, headed to their next stop where they’ll either plant mangroves or test water quality. One of the teachers stops to talk to me.

“Field trips like this, the hands-on science, are so important,” she says. “I’m glad we could come.”

“Yeah,” I say, “I wonder how many actually will become marine scientists.”

She smiles and touches my arm in a way that makes me think I’ve missed the point. “Who knows,” she says. “These kids, they go home today, and they tell their parents why the reef is important. Why losing the reef means losing the beach. Why we need to plant the mangroves and leave the sea turtles alone. Why they shouldn’t litter. And the parents – they listen to the kids. It’s the children who make the connections we need for change right now.”

As I watch them all walk back down the beach, passing other students who have come here for Reef Week from schools all over the island, I wonder how many lives changed today and how these lives in turn might change not just the future, but the present of Grenada as well.

I’ve been watching them go from station to station on the beach. And while I’ve been wilting, they’ve been waking up. They’ve been learning to use water quality testing tools and even planting mangrove seedlings with their own hands.

I’ve been marveling about how neat they stay. And it occurs to me that with kids like this, the future of Grenada is in good hands. Because kids like this, who can spend hours on the beach flying drones, planting mangroves and testing water quality – all without getting their white shirts dirty or losing the creases in their immaculately pressed uniform pants – kids like this can do anything.

Dear Nature Conservancy , we at the Peak Institute are very interesting in what you are doing and educating students about. We are located at Grey stone Road Belmont, St. Georges Grenada. We would like to be a green school and also focuses on sustainability. We will like for persons to come to our school to do presentations and also to participate on your reef week if it is still ongoing .I am the acting principal of my school and this new term we want to focus on mangroves and other ways to conserve our environment.Where are you located in Grenada and how can I get in contact with the office.

Thank you

Thank you so much for your note. I’ll send you a private email with contact information for our Grenada Office in St. Georges. I’m sure they’ll be happy to hear from you!

I am very excited about what has been happening to Grenville beach and the town which is nearest to where I grew up and so impressed by the marine scientist who are working with us and in particular with our young children who may one day become Marine Biologists and continue the important task of protecting our coral reefs, beaches and mangroves.

I do remember Long Wall in Grenville where there was a lime kiln, burning the coral reefs which used to be taken from the sea and burned to make WHITE LIME; I or most persons knew nothing of the damage that was happening to our environment. We now need to focus on all our mangroves around the island and in particular the one on Hope beach which is under threat with sugar cane planting project on going presently.