As many of us in the United States prepare to eat turkey, let’s take a look at what wild turkeys eat. The list might surprise you, and their dietary choices may help us figure out what the future holds for wild turkeys.

Like that certain uncle at your holiday dinner, wild turkeys will eat just about anything that fits into their mouths. They are the quintessential omnivores.

Acorns and azalea galls, bluegills and blueberries, crabgrass and caterpillars … they all go right in.

Prickly pear and panic grass, toothwort and tadpoles, grasshoppers and grapes, pecans and paw paws, sedges and snakes … and the list goes on.

Donate Now to Protect Nature

Help protect threatened lands and waters around the globe.

Depending on the plants species and time of year, turkeys will eat roots, bulbs, stems, buds, leaves, flowers, fruits and seeds. In search of protein, they move about the woods like a pack of velociraptors, thrashing up the leaf litter and eating anything that moves. Their quarry includes all manner of insects as well as salamanders, lizards and frogs.

From the treetops, to the ground and across forests, fields and suburban yards, turkeys make use of every inch of habitat available to them. They are even known to venture into the water to eat aquatic plants, fish and crayfish.

Peak Turkey?

The return of the wild turkey is a triumph of wildlife management. Careful regulation of hunting combined with reintroductions has produced a thriving turkey flock that nearly matches the population that existed before North America was colonized. But credit must also be given to the turkey itself.

Thanks to their dietary versatility, turkeys can thrive almost anywhere. Wet or dry, high or low, hot or cold, turkeys can make any habitat work. They only require some trees for roosting at night.

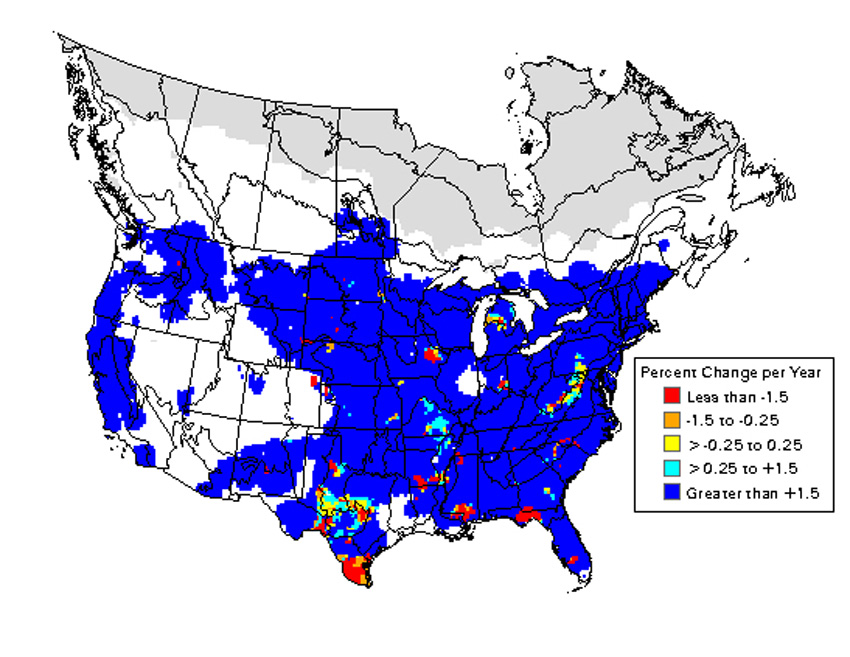

Wild turkey populations continue to grow. Across the U.S., the population is increasing by an average of 9 percent each year, according to the Breeding Bird Survey.

But how long can the population recovery continue? When do we reach “Peak Turkey”?

All animal populations have limits to growth. Food, disease, predation and environmental conditions each play a role.

But for turkeys, we can rule out food as a limiting factor. Given this bird’s extreme omnivory, other factors would likely come into to play before turkeys begin starving to death.

For example, even in the depths of winter when snow cover blocks access to the ground, turkeys can make do. Until thaw comes, they subsist on white pine and hemlock needles, mosses, lichen and the buds and stems of beech, sugar maple and hop hornbeam trees.

Predation, on the other hand, may play a central role in turkey population regulation. As most of us know, turkey is delicious!

Surprisingly, the usual suspects – coyote, bobcat and raccoon – do not commonly prey on adult turkeys. These carnivores instead focus on less formidable and wary prey such as rabbits and rodents.

Hunters kill turkeys, but regulations are set to manage for population growth. They allow hunters to take a limited number of mostly male birds.

It is nesting time that brings the most risk to a turkey. The above predators and many more seek out turkey eggs and chicks. And a hen turkey’s risk of being killed by a predator is also highest when she is sitting on the ground incubating her eggs.

A recent analysis of data from 15 Southern and Midwestern states shows that continued growth of turkey populations is limited by nest predation, combined with the limited availability of high quality nesting habitat.

In parts of this study area, peak turkey has arrived: the turkey population has begun to level off.

The research reveals that in places with the largest turkey populations, hen turkeys are less likely to have a successful brood of turkey poults.

According to the authors, this may be because all the best nesting sites tend to be occupied when populations are high. Many turkeys are then forced to choose nest sites that expose them to a higher chance of predation.

Overall the production of young turkeys tapers off while adult turkey survival remains high, resulting in a stable population.

Living with Abundant Velociraptors?

Another factor to consider as we approach peak turkey is how higher turkey populations affect the ecosystems around them.

Consider white-tailed deer. This is a classic example of a wildlife management success gone wild.

Deer populations in the absence of large predators such as wolves can easily exceed the ecological carrying capacity of their habitat. When this happens, understory plants disappear and tree seedlings are eaten before they can grow. Such dramatic changes to the understory begin to affect other animals that depend on these habitats.

Few researchers have given attention to any potential effects of expanding turkey populations on the abundance and distribution of the things they eat.

Diet is a product of preference and availability. We know that turkeys eat almost anything, but we know little about what they prefer. Their preferences are important to know because preferred items will be the first thing to disappear from the pantry as turkeys become more abundant.

If these preferred items are plants or animals of conservation concern that aren’t able to thrive while being hunted by packs of modern-day velociraptors, then we might have a problem. To put it another way, are turkeys themselves a limiting factor for other organisms?

For example, turkeys like to scratch up spring ephemeral wildflowers and eat their roots. Although deer eat such plants too, how culpable are turkeys in the decline of these flowers that crop up in early spring woodlands before trees leaf out?

One study did focus on turkey impacts by excluding them from patches of forest. The results showed that turkeys hindered the regeneration of oak trees by scratching up leaf litter in search of food. Deer cause similar problems with reduced tree seedling regeneration.

It may be a while yet before researchers, wildlife managers and hunters come to terms with the success of wild turkey management and the possibility that we are at or near the ecological carrying capacity for wild turkey in many places. The focus of wildlife managers remains on propelling population growth.

We still have much to learn about how turkeys influence the ecosystems around them.

Filling our knowledge gaps may be important as we make decisions about managing for wild turkey population stability or growth into the future. Only then can we be sure whether gaultheria and gartersnakes, spring beauty and skinks can still thrive in a post-peak turkey world.

Suburbs in our area have increasing population of wild turkeys. They are becoming a nuisance but no one has figured out a way of reducing the population.

I have recently seen turkeys in the high cascade mountains in Sourhern Oregon; this is new territory for them.

We have lots of wild turkeys in Muskoka Ontario they hang out with the deer and red squirrels I think they work together lol

I just watched a wild turkey eating the beef tallow I put out the pileated woodpecker who visits me. Is this unusual or just something I have missed before? I have up to 5 toms coming in almost daily if not twice a day at times. I have also seen 2 young or hens in the yard. They were helping themselves to the bird feeder, so I had to raise it up a little. They can eat all they want off the ground, but when they keep empting the regular seed it gets pretty pricey. I also put out some whole corn for the gray squirrels, which the turkeys always check out.

Long past time to make now “peak turkey”! We have nearly 200 of them wandering around our 4 acres in Eastern Washington because we have the tall roosting trees they prefer. What a pain! They eat everything that moves, and everything that doesn’t move. They poop everywhere. Only advantage I can think of is that we have no more ground nesting wasps since the turkeys moved in.

Is there anything related to turkeys dirt bathing, pooping and just generally messing in our pine needles that could cause our garden – yellow squash, zucchini, cucumbers, or tomatoes to die – or minimize growth in an extreme way?

My neighbor claims that wild turkeys eat songbirds. Do you know if this is true?

I am located in 06807 zip and have been observing a hen turkey being followed by two chicks for the past week.

Hen strolls around very slowly with chicks following .

The reason I searched and found this site is because my yard has a seven food deer fence but I observed something had cut off or eaten the buds on lillys.

Stephen

I am convinced a turkey eat them.

Interesting and informative article. You might want to add the introduced populations in the Cypress and Porcupine Hills of Alberta to your map. Introduced populations have been self-maintaining at these sites for many years.