What can stop cheatgrass from spreading? Not much. In the 1940s, Aldo Leopold warned this invasive plant posed a grave threat to western US habitats. Since then, it has spread. And spread. Today, it infests 50 million acres of sagebrush steppe habitat.

That’s not only bad for wildlife like sage grouse, mule deer and pygmy rabbits that rely on intact sagebrush steppe for survival, it’s bad for ranchers who are battling this invasive weed and for anyone living in areas where cheatgrass-fueled fires rage. Areas that once experienced fire an average of once every 30-150 years may experience fires an average of once every 3-5 years once cheatgrass moves in.

Cheatgrass creates a vicious fire cycle. Cheatgrass roots grow when it is still cool outside, earlier in the spring than most native plants in sagebrush habitat, and they continue growing later into the fall. The cheatgrass plant produces an extensive root system that is able to take up more water and nutrients before native plants have even started to grow. Cheatgrass then dries out by late spring or early summer and provides fuel for wildfires that clear established native plants nearby, making room for more cheatgrass to seed. Each year, the process restarts. Native plants, unable to compete and unable to withstand frequent fire, soon give way to cheatgrass monocultures.

“Big sagebrush is killed by fire,” says Chuck Warner of The Nature Conservancy (TNC) in Washington. “The only way to reestablish it is by seed. Then it takes about ten years to mature and be reasonable habitat for sage grouse or pygmy rabbit. Fire intervals of 5-7 years don’t give it much of a chance.”

Traditionally, herbicide has been the primary method of removing cheatgrass and, though some herbicides can be effective against cheatgrass, they only take out the grown plants, leaving seeds in the soil that will grow and need to be sprayed the following year.

“The herbicide doesn’t really get rid of the cheatgrass, whereas the bacteria will,” says Ann Kennedy of the USDA-Agricultural Research Service.

That’s why research by Kennedy, supported by The Nature Conservancy in Washington, is aimed at attacking the root of the problem — using soil microbes that inhibit the growth of the plant’s root system, allowing native plants to compete and diminish the number of cheatgrass seeds in the soil over time without impacting native plants or crops.

The Solution Right Under Our Noses

The world of soil microbes is a hidden realm all around us that gives scientists additional options to study. Advances in this realm are changing everything from our understanding of the human body to the way that we create materials, and they are set to change conservation as well.

“There is a genetic potential in the soil that we have not even begun to explore,” Kennedy explains. “What this research shows is that we can actually go into the soil and find those organisms or isolates that have the traits we want and use that trait selectively.”

She has been researching microbes for more than 30 years and one day, when she saw a stunted wheat plant in a field, she decided to find out what was going on in the soil nearby. She and her colleagues isolated 25,000 microscopic organisms native to the soil of Washington State and tested their effects on crops and non-native plants, eventually isolating a promising bacterium known as D7 for further testing as a biocontrol.

Testing Microbes in the Field

Working in various locations in Washington and Oregon, including the Nature Conservancy’s Moses Coulee preserve, Kennedy field tested D7 to see how it would perform in varied microclimates and what were the best conditions to apply the bacteria. When it comes to application, timing is everything.

“We have this cold loving organism that we have to be careful that we don’t put it on when the predators from the microbial community would eat it up,” says Kennedy. “It’s like the food web even at the microbial level. There are some paramecium and protozoa that would just as soon eat the microbial community as look at it.”

Kennedy’s team found that mid-October is the start of the best time to apply the bacteria, however, conditions must be right — air temperatures can be no higher than 50o F and rain needs to be coming soon in the forecast.

The bacteria need rain to drive them into the soil where it can establish; if there aren’t sufficient rains in October and November to drive the bacteria into the soil, freezing weather makes it difficult to apply the bacteria, but Kennedy has found a surprising solution to problems with frozen equipment.

“Once you get to December, the spray nozzles tend to freeze and they can crack and you’ll be out in the field and all the material goes right through that spray nozzle that is cracked so you can’t get it on. Or, if you’re going to apply by airplane, you can’t get the airplane to fly because the weather is so poor,” Kennedy explains. “I use those hand warmers that you can crack. We give those to people and you can actually warm up your nozzles on the spray rig with that.”

D7 and some other promising microbial candidates that Kennedy is working with inhibited not only cheatgrass growth, but also the growth of another invasive, medusahead — without having a negative impact on native plants, wildlife, or crops.

“A big concern was that animals would eat it,” says Warner, “but we found that this biocontrol, when sprayed on surface of ground or plants is gone after 48 hours except for the parts that get into the soil. It’s very safe for wildlife.”

And it’s cost effective. Application of the bacteria costs an estimated $8-10 per acre and once you’ve applied it successfully, you don’t need to apply it again. The bacteria establish for the next few years, restricting the growth of cheatgrass and allowing the desired plants to take over. Application of herbicides to kill off cheatgrass costs an estimated $15 per acre every year, indefinitely.

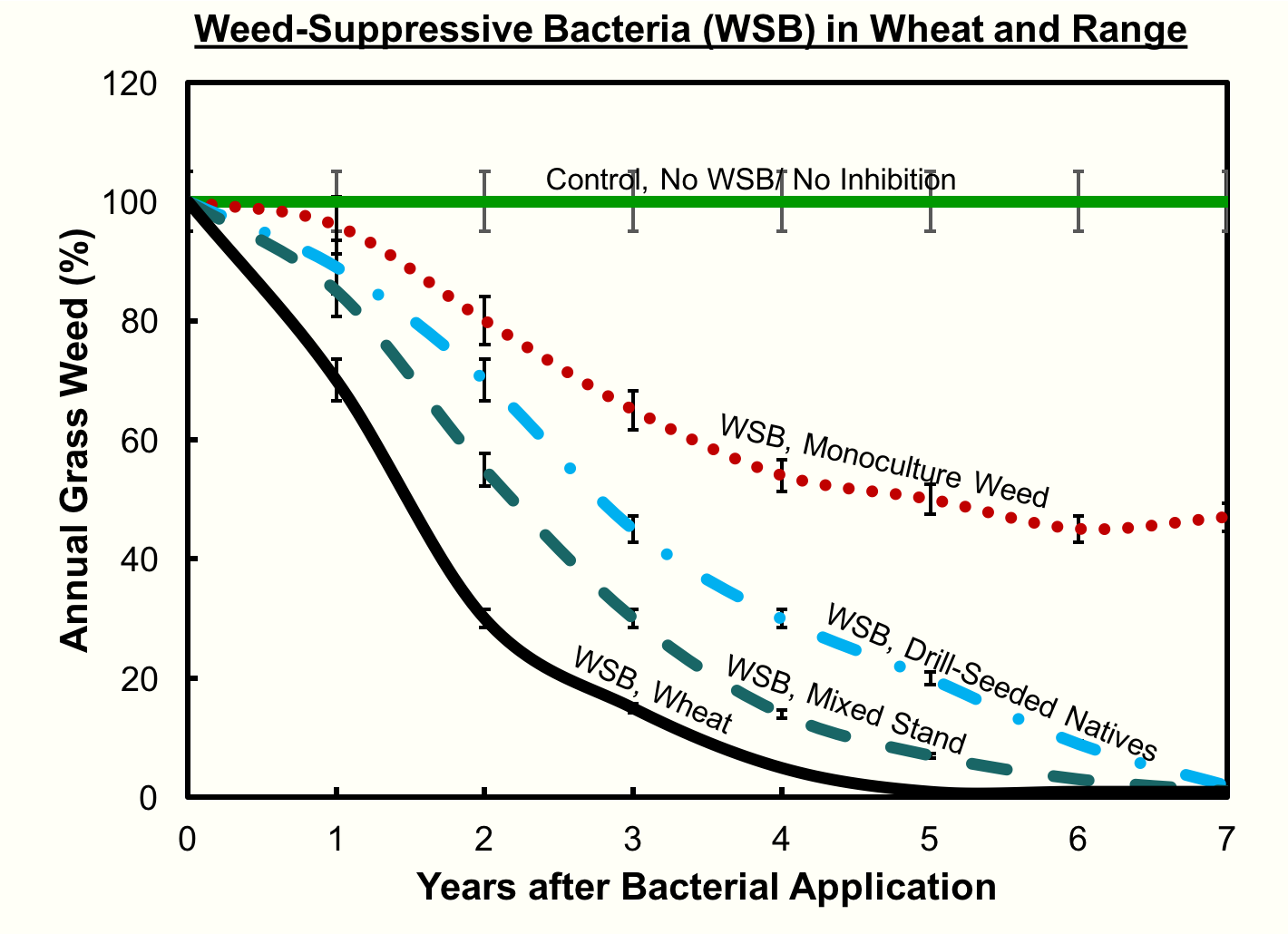

“By year three we’re seeing a 50% reduction in the cheatgrass in almost every plot that we put the bacteria in,” Kennedy notes, “except for where the bacteria didn’t survive.”

What’s the Catch?

D7 doesn’t directly kill cheatgrass. It inhibits the growth of cheatgrass roots at a critical time in the plant’s development, giving native plants a chance to compete. This isn’t a bad thing per se, but it does require a change in expectations as compared to a traditional herbicide.

“A lot of times, when people put out an herbicide, in a week they can see the dying plant and then with the weed suppressive bacteria it really takes several years,” Kennedy observes. “The grandchildren [of the microbes] have to grow and they’re the ones that inhibit the weed. In the first year we see a little bit of inhibition, but not like if you were to spray an herbicide, it takes many years for the bacteria to work into the soil and get ahold of the roots and inhibit them.”

Furthermore, Kennedy’s field tests discovered that, where cheatgrass has been established as a monoculture for a long time, the void left by the removal of cheatgrass is often filled by broadleaf weeds. This is because there is no seed bank of native plants in the soil, but the broadleaf seeds remain. Extra work may be required to reestablish the seed bank of native plants, for instance by using a traditional herbicide on the broadleaves and planting native seeds.

“If you can add a desirable plant whether wheat or natives into the system and have it grow well,” says Kennedy, “the bacteria has a much better chance of reducing the cheatgrass.”

However, it’s also important that these introduced microbes not last in the soil indefinitely. Although they are native to part of Washington, if they remained, they might cause unforeseen problems.

For instance, a bacterium known as 110 was introduced to soybeans in the 1950s to help plants fix nitrogen. It is now known that there are bacteria that could do the job better, but the 110 bacterium has been so successful in outcompeting other bacteria that it remains in the soil to fix nitrogen for soybeans all over the world to this day.

“I swore I would never put anything into the soil that would survive a long time,” says Kennedy, “An added bacterium would have to come in and do its thing for 4-5 years and then die off. We’ve selected these bacteria to be benign in the soil, so they don’t fight, they don’t have the antibiotics to fight against somebody who might come and want to eat them.”

Sowing the Seeds of Restoration

The next step is to spread the use of these “bacterial herbicides.” D7 has already been approved by the EPA and another bacterium is under review. They will eventually be made commercially available for land managers and owners who are looking for a long-term solution to the spread of cheatgrass and medusahead.

With more than 50 million acres of cheatgrass to combat, it is unlikely that the invasive will be eradicated any time soon, but these biocontrols will be important tools for beating back the invasion, protecting and restoring areas of sagebrush steppe, and could be used to create buffer zones to contain wildfires.

Kennedy will publish the data from her cheatgrass control studies with TNC within the year and continues to look at other collections and isolates of bacteria that could work against other invasive plants.

“It’s not just a one-time deal,” Kennedy explains, “we’re actually showing that the concept works quite nicely. We can find other grass weed inhibitory bacteria in the same situation where we found the other ones [i.e. where there is stunted wheat plant].”

Where can I purchase this or a product that has this to conduct an ecological study on private land? Very interested

CHEATGRASS gone forever–Naturally, with natives—

The 2022 Columbia Basin Wildlife Area Management Plan says “…cheatgrass colonization is accelerated in burned areas. Often cheatgrass revegetates as a monoculture, blanketing areas and leading to an accelerated fire cycle that favors cheatgrass and degrades the quality of the habitat for wildlife.”

Mark Larese-Casanova from the Utah Master Naturalist Program at Utah State University Extension said at https://wildaboututah.org/cheatgrass/ that “Researchers and managers are continually working to find ways to control cheatgrass in Utah. Effective control usually involves … replanting with native grasses.”

And the USDA ARS website at https://scientificdiscoveries.ars.usda.gov/explore-our-discoveries/pacific-west/nv-cheating-cheatgrass is using pre-emergents to manage cheatgrass.

=========

Researchers tested pre-emergent herbicides to control germinating cheatgrass seeds. They later seeded the treated area with selected perennial species, including some developed specifically for rangeland restoration by scientists at the ARS Forage and Range Research Unit in Logan, UT.

These plants have the ability to establish and persist in competition with cheatgrass. Over the 10- year study period, the strategy resulted in more than a ninefold increase in perennial grass densities as well as increased shrub and forb growth.

This significantly reduced the chance, rate, spread, and season of wildfires. Restoring rangelands to a healthy mix of plants increases the productivity and sustainability of agriculture in the Great Basin while also supporting wildlife and reducing wildfires.

================

Fortunately 30 years ago, I invented methods using the native allelochemicals produced by the native grass plants, to suppress 100% of those cheatgrass seeds from ever sprouting in the future.

In that way, a proper sowing of the local ecotypes of native grasses in a cheatgrass infested area, can produce 100% native cover in only 12 months. And that planting has remained 95% native cover, 30 years later.

I am having a discussion on Research Gate with Dan Harmon at USDA ARS in Reno, to see if USDA ARS would be interested in putting together a ZOOM meeting between now and Thanksgiving, to have all of the Great Basin researchers and agency people, to compare notes.

I have started the “Great Basin Grassland 100% Club”.

The “Great Basin 100% Grassland Club” is for anyone who has been able to sow native seeds to produce 100% native cover in 12 months in a cheatgrass-infested area on 500 acres and zero cheatgrass.

Purpose of this club, is to convert the 70 million acres of cheatgrass in the Great Basin, back to native grasses and wildflowers and restore that land to health, so it can start sequestering carbon for the Nation, instead of producing wildfires.

So far, one person is a member.

Info at https://www.ecoseeds.com/Great-Basin-100-percent-club.pdf

Pictures of 100% native grass cover produced in six months, when sowing into cheatgrass-infested lands north of Reno, shown at https://www.ecoseeds.com/greatbasin.html

Contact me if you know of any potential members, and send photos and locations of your site(s).

Sincerely, Craig Carlton Dremann

So interesting.

Is this product available now, summer of 2022?

Can I get D7 for my cheatgrass in north eastern Oregon?

Where can you get D7?