Looking to the tools of palaeoecology, a study published in Methods in Ecology and Evolution describes a novel approach for evaluating current and historical coastal shark communities around coral reefs by looking at what the animals leave behind: pieces of their skin. No actual sightings of swimming sharks required.

The Gist

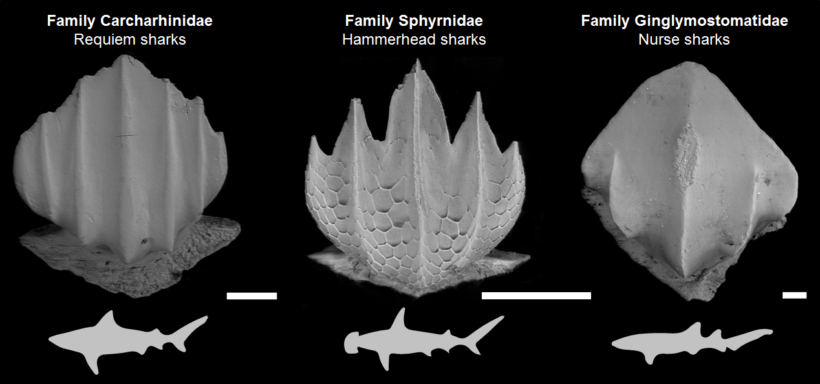

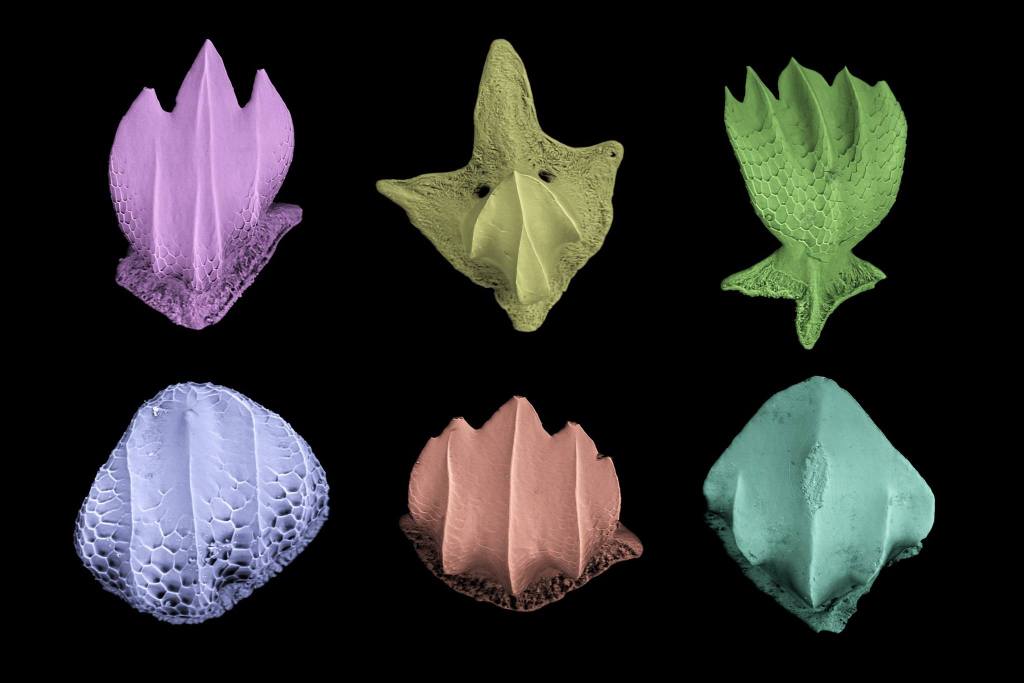

Testing their methods at the Conservancy’s Palmyra Atoll in the remote central Pacific Ocean, researchers found that the accumulation of dermal denticles – the small (<2 mm), tooth-like scales that cover the bodies of sharks and are shed as they swim – in the sediments around low-energy coral reefs correlates with shark abundances as determined by conventional surveys.

“We know coastal shark populations are declining on reefs around the world,” says Erin Dillon, lead author of the study, “but it can be hard to get a sense of the rate of decline because, well, sharks can be really hard to survey. Dermal denticles give us a proxy for measuring shark abundance – not only on recent timescales, but also going back through time so we can help fill in these missing baselines and unravel how much shark populations in specific areas have changed over decades and even millennia.”

The Big Picture

Trends matter, but because sharks are so difficult to survey accurately, scientists need more ways to collect the long-term shark abundance data necessary to map trends in shark populations, set management goals, and provide insight into the roles sharks play in the overall ecology and health of coral reefs.

Another challenge to effective shark management is that long-term survey data for coastal shark populations are relatively scarce. In many places, humans began influencing reefs and their associated shark communities before systematic monitoring, so it is difficult to know what is natural for a given reef.

This paper shows how dermal denticles can help fill these data gaps. Once they’re shed, the denticles sink and become part of the local marine sediments. As noted in the paper, “This accumulation of denticles in sediments is time-averaged, meaning that denticles shed by non-contemporaneous individuals appear together in a single temporally mixed assemblage.”

That also means denticle assemblages can preserve evidence of contemporary shark occurrences, even where sharks are rare or are not easily observed in conventional surveys. At Palmyra, for example, most evidence of tiger sharks has been anecdotal. Dillon and her colleagues discovered a tiger shark denticle in a sediment survey showing that the species, while not recorded in published surveys, has used the waters of the atoll.

The Takeaway

Scientists tested the reliability of the dermal denticle record at Palmyra Atoll, notes Dillon, “because it was the perfect place for this kind of research. There’s very little human pressure. You have a lot of sharks and the populations seem to be close to, or at, their site-specific carrying capacity. The high shark abundance meant we had a strong signal to look for in the sediments, and researchers have been conducting surveys of sharks out there for at least a decade. So there were a lot of data to compare this new method to. It was a really great collaborative effort.”

This study was an important first step prior to applying this technique to other reefs to reconstruct changes in shark abundance over time (e.g. making sure the tool works and understanding its limitations before using it). While not a replacement for the traditional methods of surveying sharks, denticles can provide important historical context and insight into changes over longer timescales than contemporary survey data alone, which makes them a useful complement to the existing toolkit.

It is an additional tool for scientists and provides, says Dillon, “a way to explore historical trends and changes. If denticle assemblages start declining in abundance over time, that tells you that something’s happening to sharks in a particular place, and it’s important to look closer to figure out what and why.”

How interesting! I had no idea how species specific the denticles are (well, duh, I guess!). And therefore how useful they could turn out to be.

In the 1970’s – 1980’s I shared an office with Pat Doyle at Scripps Institution of Oceanography. I was working on fossil Radiolarians, but Pat pioneered a study of fossil ichthyolith (teeth and scales of fish & sharks) along with our boss, Bill Riedel. Scripps has a database of fossil and modern ichthyoliths.

Jeannie Smith (at that time, M.J. Westberg-Smith)