Rats don’t always get a good rap in Western culture. They’re infamous for transmitting disease, invading our food stores, and sending seabird populations extinct. And their very name was once invoked as a watered-down curse word. (“Oh, rats!”)

But if we put our cultural prejudices aside, these much-maligned rodents are actually quite spectacular. Oceania is a particular hotspot for rodent diversity, with ample islands creating the right conditions for evolution to work it’s magic.

Australia, New Guinea, and the Solomon Islands are home to dozens of fascinating rodent species. But my particular favorites are the rats defy our cultural stereotypes. Rats that climb trees, swim in rivers, grow to epic sizes, and evade detection by scientists for decades.

Read on to discover seven of this region’s spectacular rat species.

Top 10 List

-

Vika (Vangunu Giant Rat)

Uromys vika | Vangunu, Solomon Islands

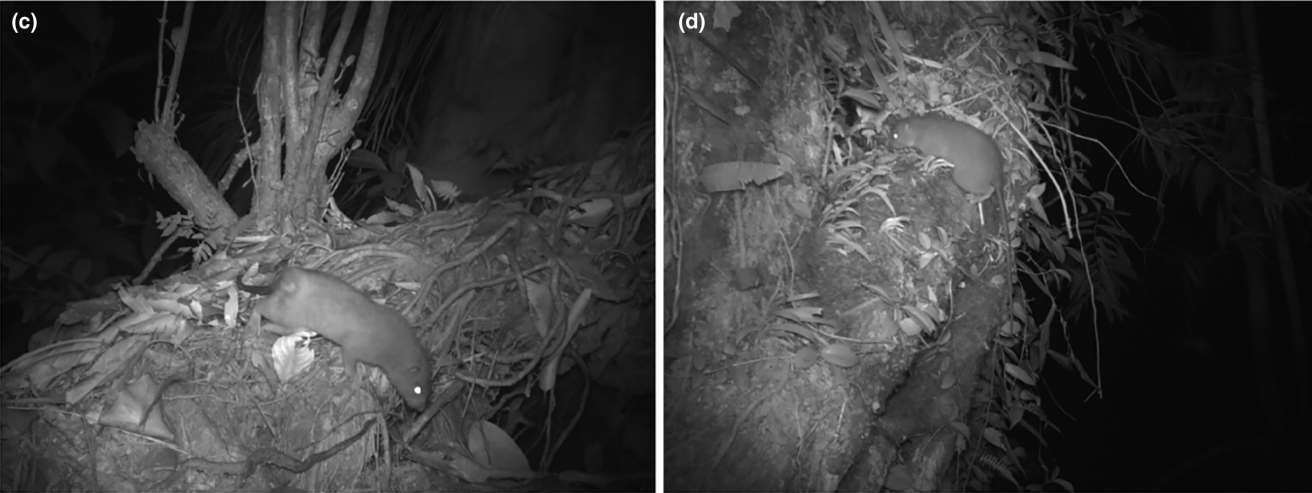

© Lavery, T.H., et al. (2023). Vangunu giant rat (Uromys vika) survives in the Zaira Community Resource Management Area, Solomon Islands. Ecology & Evolution. One of the wonderful things about Melanesia is that it still harbors new species. The Vangunu giant rat, also known as the vika, was only discovered in 2015.

Mammologist Tyrone Lavery first heard stories of a large rat species from local communities on Vangunu Island in 2010. (The locals had noticed very large poo pellets that were too big to come from the invasive black rat.) After five years of searching, he finally found it. It was the first new species of rodent described from the area in more than 80 years.

The circumstances of the discovery hint at potential threats to the species, which is almost certainly endangered. Lavery found the first (and so far, only) vika when the tree it was living in was cut down during logging operations. Many forests in the Solomon Islands are being felled for timber, and only about 80 square kilometers of primary forest remain on Vangunu. Lavery estimates that there may be no more than 100 of the animals left. The only other sighting of the vika occurred in 2021, when one animal turned up on camera traps set out by Lavery to find further evidence of the species.

-

Black-Footed Tree-Rat

Mesembriomys gouldii | Australia

© Matt Summerville / iNaturalist The spectacular black-footed tree rat is found in far north Queensland, the Kimberley region, and the savannah country surrounding Darwin. These semi-arboreal rodents are powerful and agile, and there’s something wonderfully squirrel-like about the way they move through the trees. Slightly smaller than your average housecat, they have exceptionally large hind-feet, expressive ears, and shaggy black-grey coat. Their long tail, which they use to help balance while climbing from limb to limb, is tipped with a bright white tuft.

Black-footed tree rats live in savannah woodlands and open forests, denning in tree hollows during the day and emerging at night to feed on foliage and fruits. The species is considered vulnerable by the IUCN, after experiencing a decline of 30 to 50% during the 2000s. The decline was likely caused by several interacting threats, including altered fire regimes, predation by feral cats, and habitat degradation by feral herbivores.

The species made news headlines in 2017, when the tree-rats turned up on camera trap footage farther west, in the Kimberley. Once part of the species’ historic range, the rat hadn’t been seen in the area for more than 30 years. A related species, the golden-backed tree-rat, also inhabits the Kimberley region.

-

Isabel Giant Rat

Solomys sapientis | Santa Isabel, Solomon Islands

A young Isabel giant rat, Solomys sapientis. © Patrick G Pikacha & Douglas Pikacha, Jr. Another Solomon Islands species, the Isabel giant rat was recently re-discovered after not being seen for more than 30 years. Researchers funded by The Nature Conservancy were conducting a biological survey of the Sasari cloud forest when they found a baby giant rat that had fallen out of a coconut tree.

There are only 9 specimens of the Isabel giant rat in museums, with the most recent animal collected in 1991. Adults are about the size of an eastern grey squirrel, with black-brown fur and a long, hairless black tail. A 1936 observation describes the species as: “A big and large-toothed rat which much be almost entirely arboreal, as it crushes the Ngali (Canarium) nuts and gnaws coconuts, and is found in trees felled by the natives, by whom it is eaten.”

Local people reported that the species had become rare in the early 1990s, before widespread logging started on Santa Isabel. Scientists don’t have any qualitative data about the population, the IUCN considered the species endangered due to ongoing habitat loss and hunting.

You can read more about the re-discovery of the Isabel giant rat here.

-

Bosavi Woolly Rat

Mallomys sp. nova | Mount Bosavi area, Papua New Guinea

This species is so new to science that it hasn’t been formally described, hence the placeholder scientific name, Mallomys species nova.

The Bosavi woolly rat was discovered in 2009, during the filming of a BBC nature documentary about the forest within Mount Bosavi crater. This extinct volcano crater, located in Papua New Guinea’s southern highlands, is nearly 2.5 miles wide and has walls nearly half a mile high. It’s rarely visited by local communities. A team of Smithsonian biologists, BBC filmmakers, and trackers from the nearby Kasua village spent weeks within the crater, documenting several species new to science.

First found by a tracker in the middle of the night, the Bosavi woolly rat is absolutely massive: measuring 32 inches from nose to tail and weighing 3.5 pounds. (You can see photos here.) Little is known about this new species, but scientists suspect that it feeds on leaves and roots, and nests underground beneath rocks and tree roots. Writing in The Guardian, one of the filmmakers said the woolly rat was entirely unafraid of humans, and “…sat quietly in camp, chewing on a fern and wondering what all the fuss was about as we rushed around him filming and taking photographs.”

Other mammal highlights from the expedition include the new subspecies of silky cuscus and capturing rare footage of a Doria’s tree kangaroo. The expedition also discovered 16 new frogs, a gecko, three fish, and at least 20 species of insects and spiders. There are 6 additional species in the woolly rat (Mallomys) genus. All are found in the New Guinean highlands, and most are relatively unknown to science. Three of these species, including the Bosavi woolly rat, are not yet formally described.

-

Rakali

Hydromys chrysogaster | Australia & New Guinea

A rakali in New South Wales, Australia. © David Cook / Flickr These aquatic rodents are also known as water-rats, but otter-rat might be a more fitting moniker. The rakali is one of Australia’s largest rodents, and larger enough to be mistaken for a platypus at a distance.

Rakali are adapted to life in the water, having webbed hind feet, a waterproof coat, and a thick, powerful tail that’s tipped in white. Three related species of rakali, all in the Hydromys genus, are found in New Guinea and its offshore islands.

Like the platypus, rakali live in burrows along the banks, and come out at night to forage. Predominantly carnivorous, they hunt in the water for insects, crustaceans, frogs, lizards, fish, and even small mammals or birds. Once they catch their prey, rakali typically carry it back to a regular feeding side. Rakali are one of the few native Australian species that’s adapted to eat invasive cane toads. After catching their meal, rakali flip the toad over and eats its heart and liver, avoiding the toxic glands within its skin.

-

Giant White-Tailed Rat

Uromys caudimaculatus | Australia & Papua New Guinea

© rigstanden / iNaturalist Found in the rainforests of Papua New Guinea and far north Queensland, these rats are named for their distinctive white-tipped tails. They’re one of the largest rodent species in Australia, with adults topping out around 1 kilogram (2.2 pounds).

Giant white-tailed rats are omnivorous, feeding on fruits, fungi, insects, small reptiles and amphibians, crustaceans, and bird eggs. They will bury caches of seeds around the forest, which helps disperse seeds away from their parent trees, and disperse fungi spores via their droppings. These rats are also notorious for damaging human infrastructure. They’re known to munch on electrical wires, disable cars by chewing through fan belts, and even bite through metal cans to eat the food inside.

-

Manus Spiny Rat

Rattus detentus | Manus, Papua New Guinea

The Manus spiny rat is another recently described species from Manus Island, located 300 kilometers north-eastern of mainland Papua New Guinea. The rat was discovered in 2016 by a team of scientists that included renowned mammologist Tim Flannery. (You can see a photo of the species here.)

It’s one of the largest rat species in the Melanesian archipelago, weighing nearly half a kilogram (or 1 pound). It’s known from only two areas on the island, although locals report that the species was once more widespread. Like many other island rat species on this list, the Manus spiny rat is likely already endangered.

The species’ common name references its short, coarse fur. In their paper describing the new species, the research team notes that they chose the species’ scientific name, detentus, from the Latin for “detained,” to acknowledge the species’ isolation on Manus, as well as “the recent use of the island to detain people seeking political and/or economic asylum in Australia.”

For Rattus detentus see https://www.cepf.net/sites/default/files/final-report-109784.pdf for up to date information. The species is considered to be close extinction.