The snow leopard is a legendarily elusive cat. Writer Peter Matthiessen notably spent months with snow leopard researcher George Schaller and never caught a glimpse. His National Book Award-winning account, The Snow Leopard, has led to the species being known as the “ghost cat.”

Become a Member

Make a lasting impact for nature when you join The Nature Conservancy!

Advances in science and fieldwork have helped scientists and conservationists gain a better understanding of snow leopards, but there’s still much to learn – and better information is necessary to protect this species.

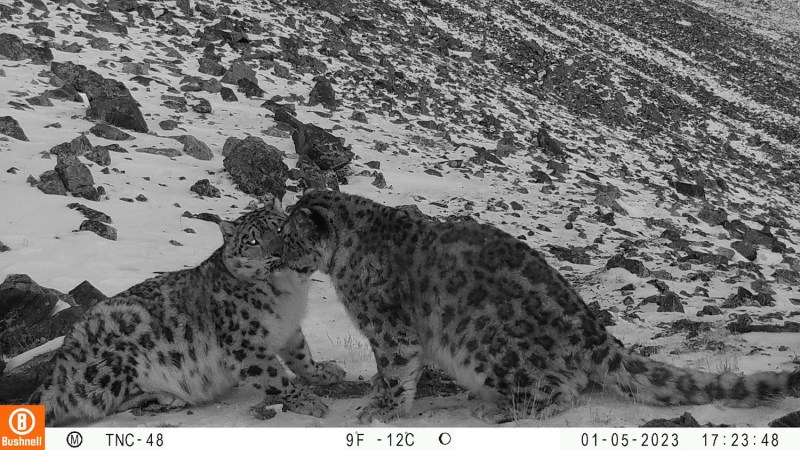

The Nature Conservancy and partners conducted a population study of snow leopards in Mongolia from 2016-2022 using camera trap surveys in the Bumbat and Sutai mountain ranges. They determined those ranges are really important for leopard populations.

Now, Erica Anderson, conservation information manager for The Nature Conservancy in Connecticut, is building off of that data to give us a deeper understanding of snow leopards. She realized expanding her new expertise in Geographic Information Systems (GIS) from Connecticut to Mongolia’s formidable mountains would be worth it…for these big, mysterious cats and the environmental questions they could help answer. Anderson traveled to Mongolia in summer 2025 for a research trip and is helping to connect wildlife corridors for species on the move.

“My work was specifically about using GIS as a way to depict where you might find a snow leopard, particularly in the Altai [Western Mongolia,]” says Anderson. “What’s happening on the ground? How does it play out in reality? We want to identify snow leopard habitats and understand their behavior so we can connect it with other current research, and then model habitat suitability across the region.”

“If we can find the ways leopards get from Point A to B through modeling and which habitat is best, we can tie that together with community-led conservation to mitigate herder-leopard conflicts,” she continues.

Researchers have population information (camera data from Mongolia showed numbers there are growing), but we need to know where they travel and how to preserve those habitats. Plus, it helps snow leopards avoid coming into contact with herding communities, especially as livestock populations grow rapidly and need more land.

Some of Anderson’s work with TNC in Mongolia is supporting community-led conservation program, to support and prevent further loss of nomadic culture and assist in residents’ and herders’ livelihoods

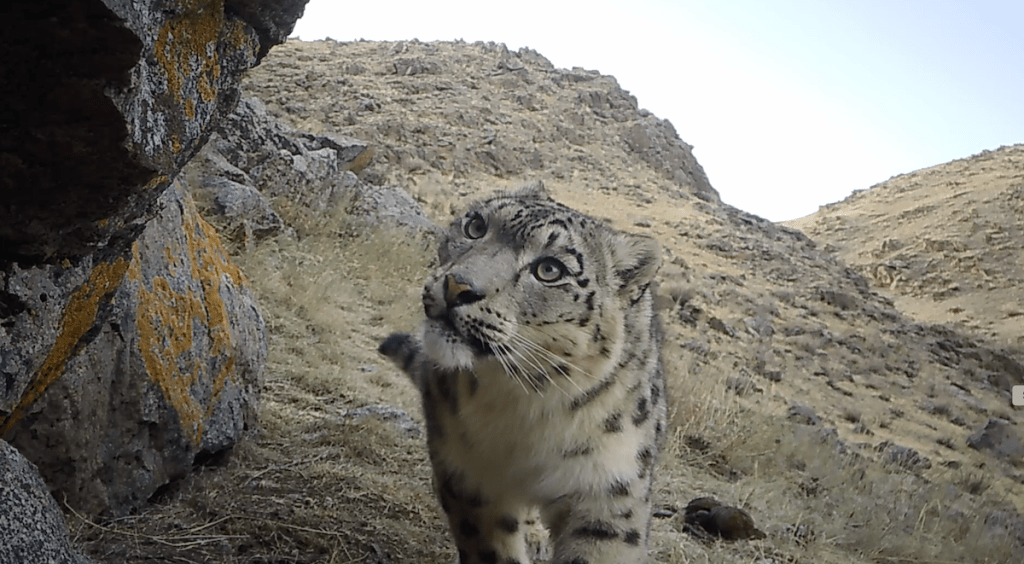

Take a good look at these cool cats. They’re short. They’re stocky. Their back legs and back feet are long.

“These big paws, their big mitts help them specifically in this habitat where it’s really rocky and really hard to maneuver,” says Anderson. “Everything that we think is difficult, they’re like, ‘No problem!’ They move really fast across rugged terrain because of their build. See how long their tails are? They’re about the same or a bit longer than their body length—that helps keep them balanced.”

Their pelage—the leopard’s coat color and patterns—blend in with their mountain habitat. It’s one of the reasons they’re so difficult to locate. And that’s where camera trap videos come in.

In the video above, a snow leopard is seen sniffing around the camera and giving…well, a stink face. If you have a cat at home, you’ve seen the move: They pull back from a smell, mouth open, like they just got a whiff of something terrible.

“That’s the Flehmen Response!” Anderson says. “It’s essentially when snow leopards smell hormones.” Clearly, a buddy or a rival had been to that camera first.

But how did the team ensure snow leopards would even come that close? “The cameras were set up at known scrape and marking sites. So this is just them coming around. They’re not baited or anything,” Anderson explained.

This incredible footage features a snow leopard vocalizing. It’s not a big roar and it’s not even a deep meow. In fact, it’s sort of jarring. The big cat’s not giving off a distress call though.

“The sound in the video is a ‘yowl.’ (They can’t roar because their vocal chords are too small!) This helps them communicate across longer distances. They can still growl though,” Anderson says. “They also ‘chuff’. It’s unique to them. It’s like a series of little puffs coming from a big cat. It’s a social form of communicating and is non-threatening. Other research says they purr, which is cool!”

While the camera sites were known as high visitation areas, it’s still a relief for the research team to spot their subjects.

“You’re always feeling hopeful until you actually see them, but it’s never a guarantee,” says Anderson. “There are over 200 cameras we’ve set up between 2016 and 2022. But not all of them end up capturing snow leopard footage,” Anderson added. “Their coat patterns are also really distinct like a fingerprint, so we can tell one from another at the cameras.”

Camera traps pick up some bonus footage, too. For these, that included corsac fox, grey wolf, marten, Siberian ibex, Chukar Partridge, Pallas Cat, goats, sheep, eagles, rabbits and other birds. After all, snow leopards are a keystone species, which means that their presence indicates a healthy habitat for their prey and freshwater sources. We’ll be sharing images of other Mongolian wildlife in an upcoming Cool Green Science blog.

Right now, Andeson is focused on making sure the data is best utilized for conservation.

“There’s a big gap in the sense that a data repository does not exist,” says Anderson. “There have been lots of cameras. And we more so need access to all the data and to pool the knowledge together to make more leaps and bounds because we know the data exists.”

I very much hope that TNC is collaborating with a terrific organization that has been involved in snow leopard research and conservation since 1981 and that I have donated to for a number of years – https://snowleopard.org/about/

The website has a list of partners divided into types – foundations, zoos, business, etc – and I didn’t find TNC in any of the partner lists. TNC and Snow Leopard Trust could form a powerful team for the good of the snow leopard.

This is such amazing footage; it’s letting us into a special world.

Good work 🐾🔝💕

Amazing animals to be preserved and celebrated. This is the best footage I’ve ever seen of snow leopards in the wild. Thank you to all the devoted researchers and conservationists of these wonderful cats.

Incredible footage! Thank you so much for what you are doing for these amazing creatures!

If you will look real close at the shape of the face

Of this leopard you will see that it’s related to the

Sabertooth tiger, check the DNA .