India, the world’s fifth-largest economy, is poised to see significant increases in demand for wood and wood-related products. Over the years, India has seen steady growth in forest and tree cover in different parts of the country (Forest Survey of India, 2023). Still, domestic timber production is unable to meet mounting market needs (Kant and Nautiyal, 2021).

India’s interest in transitioning towards more sustainable food and land use systems manifests in multiple ways. The Government of India has committed to restoring 26 million hectares of degraded lands and creating a carbon sink of 2.5-3.0 billion tonnes of CO2e through additional forest and tree cover by 2030 (Prime Minister’s Office, 2019).

In addition, growth in farm incomes and agricultural credit are important policy goals. These commitments toward climate mitigation, land degradation, and farmer wellbeing present an opportunity to strengthen tree-based regenerative agricultural practices, particularly agroforestry.

Agroforestry is defined as a land use system that integrates trees and shrubs on farmlands and rural landscapes to enhance productivity, profitability, diversity and ecosystem sustainability (NAP 2014). These systems foster ecological and socio-economic interactions, presenting both challenges and opportunities for industries using tree-based products and for the farmers growing these trees.

To better understand the complex interplay between market demand and farm supply of tree products, TNC researchers analyzed wood trade data, interviewed key market stakeholders, and conducted farm household surveys.

This culminated in a national workshop co-organized with CIFOR-ICRAF, which brought together decision-makers from wood-based industries, farming communities, and government and non-government agencies. The goal of the workshop was to further unlock the potential of India’s National Agroforestry Policy by identifying key strategies to encourage tree planting by farmers and enhance market demand for smallholder produced wood. This note summarizes insights that emerged from the workshop and makes recommendations based on multi- stakeholder deliberations.

Key Trends and Challenges

Tree-planting by farmers has the potential to raise incomes, meet commercial needs and contribute to public commitments to restore lands and mitigate climate change. However, critical bottlenecks related to market structure, farmer needs and government regulations, especially felling and transport restrictions, will need to be addressed.

1. Growing Market Demand

India is projected to see a 70% increase in demand for wood and wood-related products by 2030 based on growth in the Indian economy (Panel B, Figure 1, Kant and Nautiyal 2021). Wood demand comes from the construction sector and associated industries such as plywood and wood-based panels, followed by paper and pulp and the furniture sectors. Wood supply while relatively stable over the last decade, showed some growth in imports of sawn and pulpwood (Panel A, Figure 1).

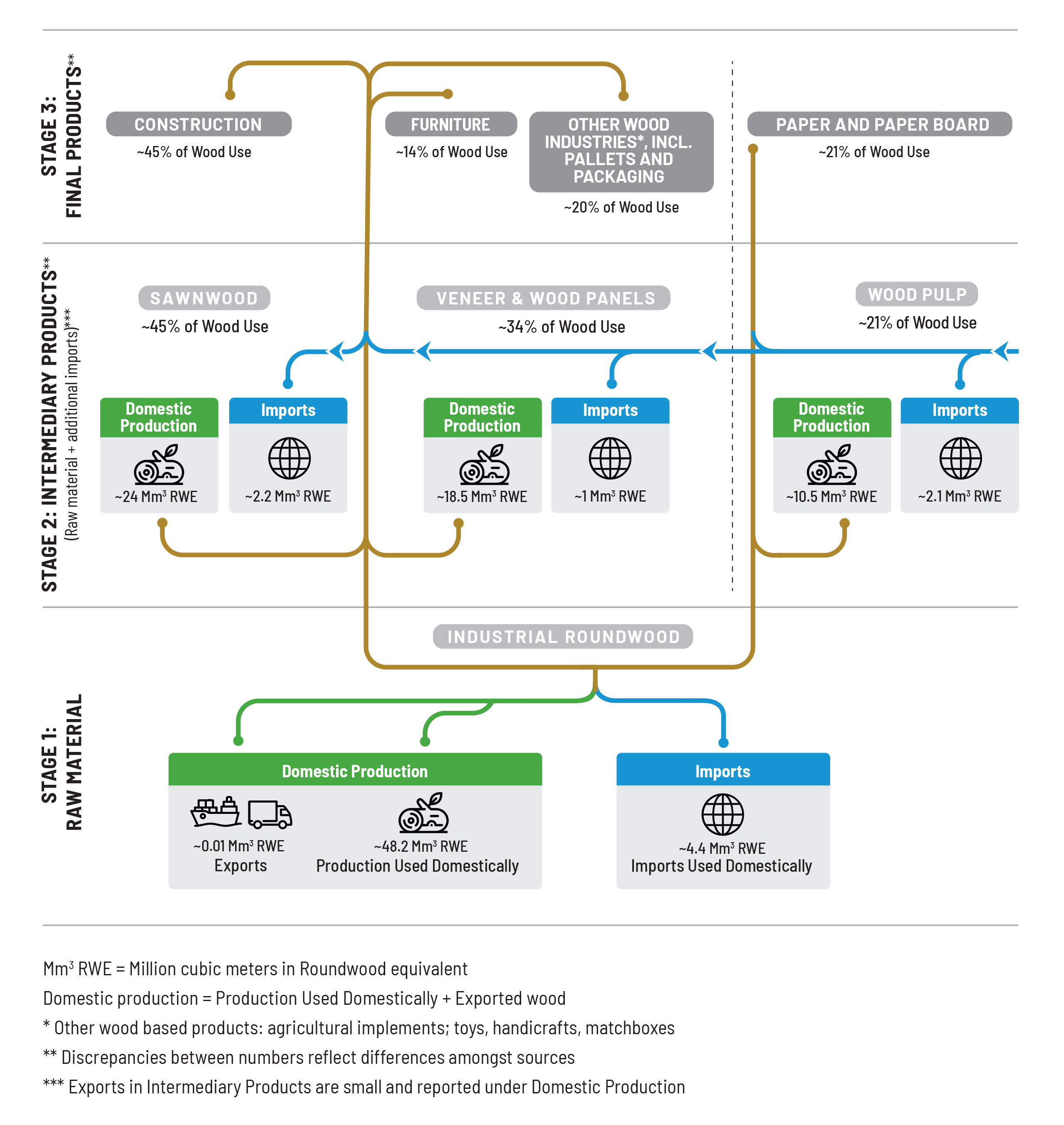

Figure 2 provides further details on the wood value chain in India, showing how raw material (roundwood) is used to develop intermediary and final wood products. Approximately 53 million cubic meters (Mm3) of roundwood serves as the basic raw material for India’s wood-based industries. Some 92% of roundwood is domestically produced, with the remaining 8% being imported. This roundwood is used to develop intermediary products such as sawn wood, veneer and wood panels, and word pulp, some of which are also imported.

Among the final sectors in the wood value chain (Figure 2), construction accounts for 45% of total national wood use, followed by the paper and paperboard industry (21%). Other industries, including the furniture and pallets and packaging account make up the rest of national wood demand. While the construction sector dominates final wood use, projections and industry experts point to increasing hard wood substitutes and an upward trend in market demand for products such as plywood, furniture, paper and pulp, and pallets and packaging (TNC Research and Kant and Nautiyal, 2021). These industries will likely fuel growth in demand for wood in the coming years.

While the bulk of wood used in India is domestically produced, Indian industries also rely on wood imports. India is a net importer of wood, with wood exports valued at approximately 6% of the value of major wood imports in 2019 (Kant and Nautiyal 2021). Several differences between domestic and international traded wood sectors appear to contribute to growth in imports. Key informant interviews with industry actors suggest that imported timber is likely to be more reliable, meet desired specifications and be graded as expected. Dependable grade-based price variation allows buyers to more readily choose wood that fits their budget and requirements (TNC Research 2023). In contrast, domestic wood sales hubs (mandis) are informally managed, limited in number and often located far from farming communities, leading to inconsistent and uncertain local supply.

2. Wood Supply and Trees Outside Forests

The main source of domestic production of wood is India is Trees Outside Forests (TOF). TOF cover all trees outside recorded forest areas. Thus, trees growing in private lands, i.e. through agroforestry supplied trees, fall into this category.

Figure 2 presents the distribution of different sources of wood used in Indian markets. Overall, some 83% of domestic needs are met by domestic production and 17% through imports. TOF make up approximately 93-96% of the domestic wood production, with the remaining (4-7%) coming from state forests and plantations.

As trees are not an annual crop, domestic tree production is not expected to increase significantly in the short term. Thus, any gap between domestic supply and the growing demand identified in Figure 1 (Panel B) will likely continue to be filled by imports. However, given the distribution of wood sources and expected growth in demand, agroforestry offers farmers a huge opportunity to gain wood market share.

While agroforestry offers a potential income diversification strategy for famers, there are many implementation challenges. Tree production depends on agroecological and climate conditions and needs to respond to market signals. Farmers also have limited access to technical information, quality planting material, peer-networks and finance. Additionally, growing trees requires dedicating land to longer-term investments with uncertain returns. Thus, the risk-return ratio is high, even if tree harvests are lucrative.

3. Regulatory Challenges

India has many policies and schemes to promote agroforestry and ToFs, including its 2014 National Agroforestry Policy (NAP). Some states, including Gujarat, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, and Maharashtra, have sought to streamline their timber felling and transport regulations in line with the National Agroforestry Policy. Additionally, in 2023, the Government of India launched the National Transit Pass System (NTPS), a pan-India one-nation one-transit initiative to facilitate the seamless transit of timber, bamboo, and other forest produce across state borders. Twenty-four states (including union territories) have removed many tree species from Felling and Transit Regulations on non-forest areas and private lands. Evaluating the impact of the changes introduced by the NTPS on wood production and harvest will be key.

Though there has been an easing of felling and transit regulations on forest areas and private lands, differences in state policies and legal ambiguities continue to create challenges for both farmers and producers harvesting and transporting timber. Consequently, increases in tree planting by farmers has progressed slowly, partly due to inadequate enabling conditions in the form of government extension services, communication of changes, public nurseries, and attention to issues such as land and tree tenure, gender, and social inclusion (Duraisami, Singh, & Chaliha, 2022).

Furthermore, while agroforestry is overseen by the Agriculture Ministry, other government agencies, especially forest departments at the state level, have significant interests in tree product harvesting and sales. Addressing this layer of complexity requires multi-sectoral approaches, which have been challenging to implement.

Recommendations

The national workshop in July 2024 convened a diverse group of stakeholders committed to advancing agroforestry. Discussions concluded that scaling agroforestry requires a three-pronged approach: aligning practices with growing market needs, improving the risk-return profile of farm tree production, and creating enabling conditions that reduce transaction costs. Implementing these strategies will require active collaboration among market players, government and non-government agencies, researchers, and farmers.

Recommendation 1: Align with Market Demands

- Promote Market-Oriented Agroforestry: Encourage farmers to plant fast-growing trees in agro-ecologically suitable areas to meet industry demand. Create an agroforestry dashboard with spatial maps that show market hubs, prices, agro-ecological zones, areas growing trees and nurseries.

- Conduct Wood Industry Assessments: Facilitate industry-research institution partnerships to enhance research on sustainable plantation management, focusing on ecological and market suitability. New business models are needed to enhance biodiversity, enthno agroforestry and to minimize environmental impacts.

- Standardize Wood Harvesting Practices: Reevaluate plantation management and address knowledge gaps in silviculture practices among farmers through forest, agriculture, and horticulture institutions. Wood industry associations can advocate for minimum wood quality standards and clarify standardization requirements.

- Enhance Wood Traceability: Develop an online tree registration system with species information and Certificates of Origin to advance supply chain transparency. There is also a need to incentivize adoption of national standards and code of practices related to wood and wood products to improve product quality. The recent Indian Forest & Wood Certification Scheme (2023) introduced by the Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change may contribute towards some of these needs, particularly if industry associations also advocate for certification and standardization.

- Strengthen State Market Exchanges: Buying and selling of timber is done largely through unorganized markets (mandis). Electronic markets to improve product information and market efficiency may feasible and is being trialed in Punjab. As the sector grows, industries can also be expected to invest in such innovative trading platforms.

Recommendation 2: Incentivize Tree Planting

- Ensure Financial Support and Risk Reduction: Incentivize tree planting through payments for ecosystem services and the use of varied state-specific schemes that offer subsidies, grants, credit and insurance. Financing may also be required at the supra-farmer level to bring larger investments into agroforestry value chains. Risk reduction strategies, such as insurance to address fire, pest and animal risks, need to be explored through linkages with financial institutions.

- Leverage Carbon Markets: Explore carbon finance for agriculture and forestry projects by linking farmers with carbon market developers and supporting farmer producer organizations who may be able to bring a larger number of producers together. The carbon market is expanding in India with carbon developers expecting to generate significant carbon credits by aggregating small farmers growing horticulture and tree products.

- Understand challenges to Buy-back Contracts: Buy-back contractual arrangements between industries and farmers reduce market uncertainties. However, such agreements (examples include WIMCO in Uttarakhand, ITC BPL in Andhra Pradesh, and JK Corp and BILT in Odisha) have been challenging to implement because of non-compliance issues, disagreements over terms, un-expected shocks resulting in tree mortality etc. Still, as this approach is used in many parts of the world, it would be useful to investigate legal and other barriers to implementation in India.

Recommendation 3: Strengthen Enabling Conditions

- Promote State-Level Agroforestry Policies: States can create action plans that are aligned with the National Agroforestry Plan and address local needs with local language advisories. Bihar’s Agroforestry policy (2018) serves as a model, highlighting economic and employment benefits, and advocating for agroforestry industrial zones. CIFOR-ICRAF, in collaboration with state governments and the Forest Department, has developed draft state-specific Agroforestry Policies for Assam, Tamil Nadu, Haryana, Andhra Pradesh, Odisha and Rajasthan. The Government of Assam has already put forward the Assam Agroforestry Policy (2024), and other states are in the process of doing so.

- Ensure Quality Planting Material Production: Access Quality Planting Material (QPM) of agroforestry species is essential. ICRAF and CAFRI have developed guidelines for QPM production for agroforestry species (CAFRI-ICRAF, 2019), contributing to agroforestry’s inclusion into the ‘Rastriya Krishi Vikas Yojana (Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare, 2025). ICAR-CAFRI now serves as a Nodal Agency, providing technical support for QPM supply, certification, and nursery accreditation.

- Develop Consortium-Based Agroforestry Models: Bring together different players across the supply chain to provide farmers with access to input and output markets. Tamil Nadu has a successful model that includes nurseries, Krishi Vigyan Kendras, and various wood-based industries, which could be further evaluated and replicated.

- Enhance Extension and Nursery Support: Boost agroforestry by providing farmers with extension services through Krishi Vigyan Kendras. Nursery certification currently being promoted by ICAR-CAFRI has the potential to scale the delivery of quality inputs for agroforestry. Industries also need to scale their efforts in nursery development and outreach to farmers, possibly through corporate pledges to buy back from smallholders.

- Enhance participation of tree farmers in post-harvest value addition: Tree farmers rarely engage in adding value to harvested produce, often selling trees to middlemen who harvest and transport trees from farms. Establishing a micro and small-scale enterprise ecosystem for low-investment post-harvest activities will create jobs and improve supply chain efficiency while offering better value to agroforestry farmers.

- Recognize that ‘wood is good’: The Government can encourage the use of wood in public procurement processes related to sectors such as construction and housing. If facilitated through transparent electronic marketplaces, this will likely create a steady demand for wood-based products while maintaining good governance standards.

Conclusions

A multi-faceted approach to agroforestry can advance India’s green economic transition. To operationalize a sustainable and profitable agroforestry, we will need to align agroforestry practices with market demand, provide robust financial incentives, and recognize the importance of acting at state and national levels. “Wood is good” and can contribute to climate mitigation, land restoration, and enhanced livelihoods for farmers. Scaling agroforestry will, however, depend on collective and collaborative action among market players, government agencies, researchers, and farmers.

Best article. Please share widely