Nature’s potential to help protect people from the negative impacts of climate change has been receiving a lot of attention recently. But what if we are actively losing nature’s protection as we speak?

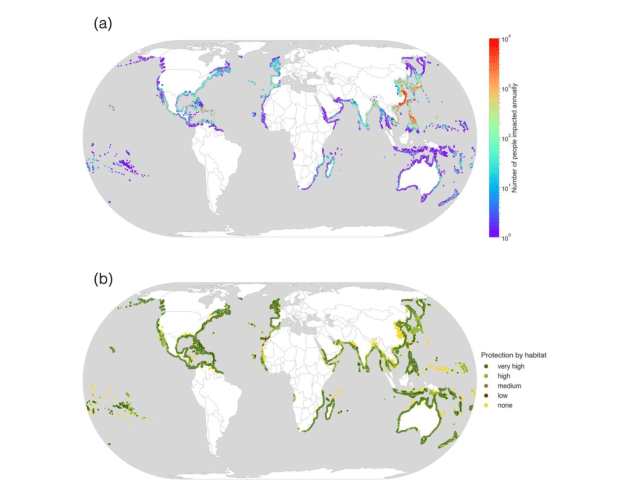

Considering that 68 million people in low-lying coastal areas around the world are at risk from tropical cyclones every year, it seemed an important question to answer. So we turned to modeling to begin to find out. Specifically, we wanted to know how many people are currently receiving protective benefits from coastal ecosystems (like mangroves, coral reefs and salt marshes), how this number has changed in the past, and how it may change in the future.

Mangroves, Coastal Forests, Reefs, Salt Marsh and Wetlands

Published in Environmental Research Letters, our research shows that of all the 68 million people at risk, one in five is currently protected by coastal ecosystems such as mangroves, coastal forests, reefs, salt marsh and wetlands. But, over the last 30 years, the share of people protected by ecosystems has decreased by 2%, primarily because of the loss of those coastal ecosystems.

A 2% decrease may not sound like much, but given the number of people potentially affected by tropical cyclones every year, a 2 percent change means that 1.4 million people per year have lost protection.

| Top five highest ranking areas in terms of protection by coastal ecosystems | |||||

| Number of people protected from tropical cyclones annually | Proportion of impacted people protected (%) | ||||

| 1 | Philippines | 5M | 1 | US Virgin Islands | 92% |

| 2 | China | 4M | 2 | Saint Vincent and the Grenadines | 84% |

| 3 | Japan | 2M | 3 | Saint Kitts and Nevis | 72% |

| 4 | Hong Kong SAR | 0.8M | 4 | Hong Kong SAR | 70% |

| 5 | South Korea | 0.5M | 5 | Northern Mariana Islands | 69% |

In fact, more than 80% of this decrease in protective services is due to ecosystem degradation and loss. The rest of the decrease is explained by where coastal population has increased in relation to coastal ecosystems and cyclone risk. Here, we observe a concerning trend: over the last decades, coastal populations have grown predominantly in areas unprotected by ecosystems.

Coastal communities are vulnerable and losing nature’s protection. We estimate that, with climate change, 40% more people in coastal areas (annually around 27 million more than are already at risk) could be impacted by tropical cyclones each year. This increase does not even include effects of future population growth or sea level rise, which can be expected to further exacerbate the dangers.

An important way to counter the challenges is to prioritize conservation of coastal ecosystems. For example, in the Philippines alone, each year, 5 million people benefit from coastal protective services by ecosystems.

Prioritize Protecting Existing Coastal Ecosystems

As our study shows, if governments, international organizations and NGOs, communities, and the private sector don’t act now, more ecosystems and the protection they provide could be lost, leaving more people unprotected.

The first priority should be protecting existing coastal ecosystems. However, the potential of ecosystem restoration to buffer some of the impacts of climate change and previous ecosystem loss should not be neglected. To quantify this, we modeled how protective services with regards to tropical cyclone risk could be increased by restoring mangrove habitats.

Globally, gains in protection are rather minor (only 0.33% of all people at risk). But, spatial scales matter: Restoration of coastal ecosystems can be very important in certain areas, especially in island states. For example, in Bermuda, mangrove restoration could nearly double (from 43% to 81%) the share of people protected from tropical cyclones by coastal ecosystems.

Our results highlight that Nature-based Solutions (NbS) should not be seen as a silver bullet for disaster risk reduction everywhere. At the same time, ecosystem restoration can be very impactful in certain areas, such as small island states in the Pacific and the Caribbean, which is why it is important to prioritize areas for implementation based on risk assessments. Policy makers, risk managers, and conservation and restoration practitioners can use this information to identify high priority areas.

For instance, populated coastlines in areas of high tropical storm risk, where coastal protective services have been lost recently, are an important target for restoration of coastal ecosystems.

Furthermore, while restoration plays a vital role in recovering some of nature’s protection lost over the last decades, it is essential to conserve existing coastal ecosystems. Maintaining natural habitats is always more cost-effective and better for biodiversity than restoring natural habitats, all else being equal.

Our study identifies the most important areas where coastal ecosystems need to be protected for risk reduction: Creating new protected areas, where coastal ecosystems are currently providing significant protective services but are not legally protected from development, e.g. at densely populated coastlines in areas of high tropical storm risk, could complement other climate adaptation strategies.

Join the Discussion

1 comment