I love birds and bird watching – from the aerial twists and turns of the agile barn swallow, to the sally and hover of a flycatcher catching a moth, to the adorable top knot of the rotund California quail. Birds bring me great personal enjoyment and define a part of my being.

The technical scientific term for this is a “cultural ecosystem service” – the non-material benefits that ecosystems and biodiversity therein provide to people.

One important place for bird conservation is in farmlands. Yet, conservation of birds in agricultural systems is a complex issue, in part due to it being private land, and in part because birds play many roles that impact crop production.

For example, a flock of invasive European starlings or ring-billed gulls may fly into a fruit field, decimate crops, and leave feces behind with foodborne pathogens that could make people sick. On the other hand, promoting predatory bird species like the American kestrel may deter fruit-eating birds, improving yields and the economic well-being of farmers.

Such controversies have often led to conflict over conservation-friendly farming – is farming in harmony with conservation efforts increasing the benefits or risks from birds?

This inspired me to set forth to survey birds and farming practices over 4 summers on 27 diversified farms across the US West Coast states of Oregon and Washington.

Through this, I was able to maximize my life list by observing 15,682 individuals from 111 species during the designated bird survey periods alone. I saw species such as dazzling lazuli buntings, adorable bushtits, and iconic ospreys. I saw interesting interactions such as a blackbird mobbing a crow, who turned and began mobbing an osprey, who then turned and started mobbing a bald eagle.

I then analyzed my more than 15,000 bird observations with input from collaborators at The Nature Conservancy and several universities to examine how conservation-friendly farming practices and abundant natural habitat in the broader landscape (a 2.1-km circle around where I surveyed) impact the impacts of birds on farms and conservation efficacy.

That is, how can we manage farms to promote the benefits of birds and minimize harm?

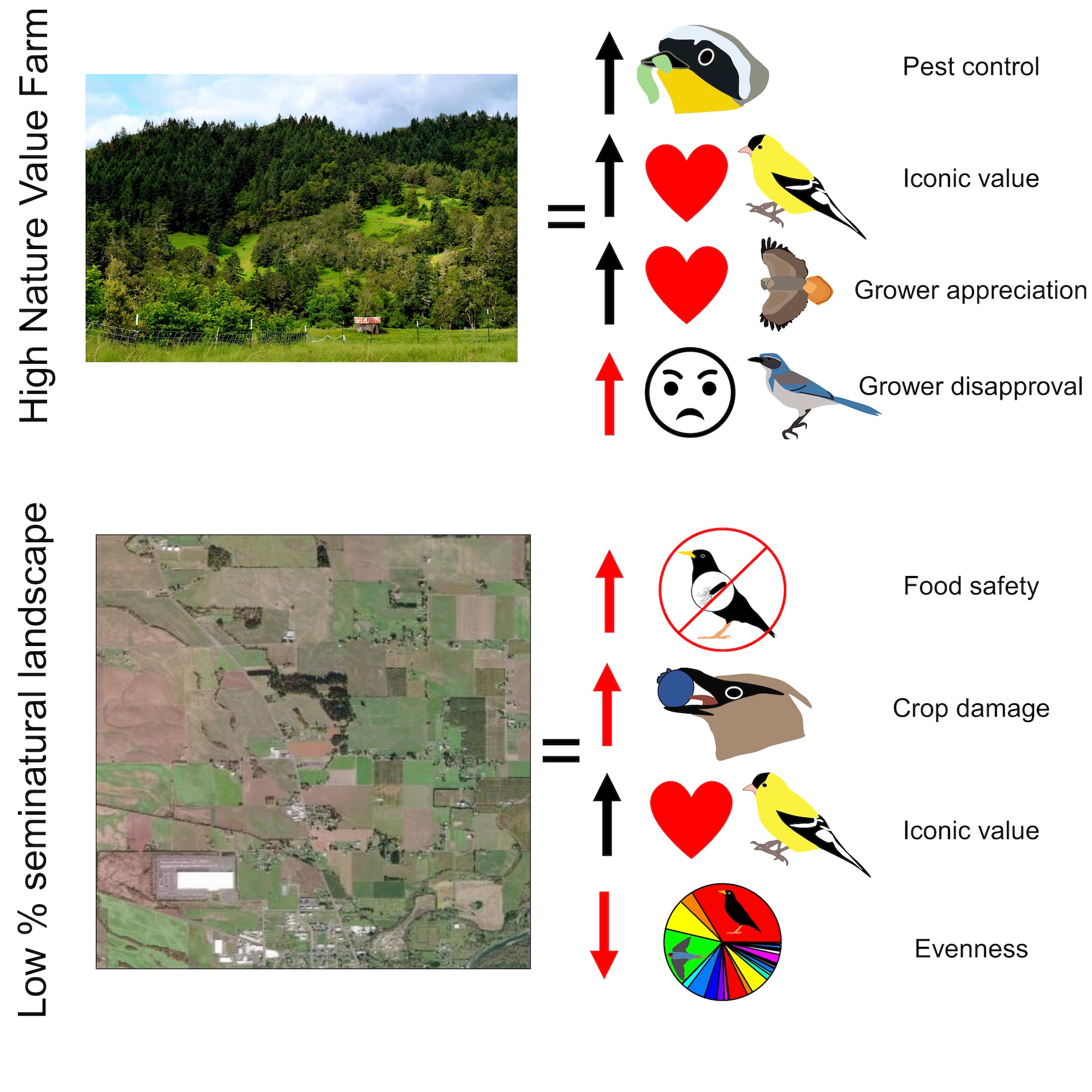

Overall, we found that an individual farmer can implement conservation-friendly farming practices to promote beneficial birds — including both birds that eat pests and birds that provide cultural services to the farmers.

Overall, we found that an individual farmer can implement conservation-friendly farming practices to promote beneficial birds — including both birds that eat pests and birds that provide cultural services to the farmers.

The farmer could, for example, provide hedges to promote insect-eating birds near crops that are being damaged by insects. They could also take actions such as integrating livestock into their farm, which can benefit birds through additional grassland (e.g., northern harrier and savannah sparrow nest sites) and structures to nest on (e.g., barn swallow and cliff swallow nest sites). Another strategy could be retaining riparian areas or wetlands that can promote birds and provide other important sustainability benefits such as erosion control.

The problems associated with birds, however, were more impacted by the amount of natural habitat in the broader landscape than what the individual farms were doing. This means that to minimize harms associated with birds, there needs to be community management of agricultural systems.

Organizations such as TNC or Audubon Society have programs in place to do so such as Audubon Certified Grazed on Bird Friendly Land. However, there will likely need to be greater community-wide uptake by farmers to really maximize the benefits of birds to farming while minimizing issues from birds.

Altogether, our work suggests that wide-scale preservation of natural habitat will help promote birds to maximize their benefits to farmers and conservationists, while minimizing their harms to farmers and human health. However, we also have a long way to go to incentivize farmers and other private landowners to do so.

Olivia Smith is a research associate in the Ecology, Evolution, and Behavior Program at Michigan State University.

Hi, Olivia. Avid waterfowl and gallinaceous bird enthusiast here.

Very troubled by the impact of corn monoculture for ethanol that has decimated Conservation Reserve Program leases and amount of enrolled acreage in the MW. I believe the direct impact of trading fallow CPR lands for corn for ethanol has serious consequences for a wide variety of species of waterfowl and upland birds (and even ruminants).

Wondering if you could comment on that specific issue?