I walked along a little path when suddenly the ground in front of me came alive in a whir of feathers. I reflexively jumped back as 20 California quail flushed before me. They flew rapidly away for a short distance, then set their wings as they glided into a patch of grass.

Just as they were about to land, a larger avian form appeared out of nowhere. A Cooper’s hawk. It swooped down on the vulnerable quail, followed by an explosion of feathers. The hawk bent over, tearing at the quail’s breast.

By the end of my walk, I’d see this exact same sequence happen two more times. I was filling the role of hunting dog for migrating Cooper’s hawks. A spectacular day for a naturalist, but I was used to such bird interactions at this place, an organic farm known for its conservation-friendly practices. It’s where my family got its produce in the summer. It’s also where I’ve had some of my best bird sightings around my home in Boise, Idaho.

It’s hardly a secret among conservationists (or birders) that farmlands can be vitally important to birds, particularly when wildlife-friendly practices are incorporated into farming, such as planting multiple crops, using cover crops, integrating hedgerows or prairie strips into fields, or reducing tillage and pesticide use. To encourage farmers to adopt such practices, conservationists often tout the many ecological services that promoting agricultural diversity provides, including natural pest control and pollination.

But there’s another side: birds can also be a significant problem on farms, eating crops or defecating on them. That spectacular sight on my local organic farm carried a downside to the farmer: those quail were devouring many crops. In fact, I flushed one of those quail flocks out of the kale crop. They were not a welcome sight on this farm. The Cooper’s hawks, on the other hand, were encouraged to stick around.

Considering farmer attitudes and values is essential to ensuring successful and long-lasting conservation planning. That is because a farmer with a positive view of birds is more likely to adopt conservation-friendly practices.

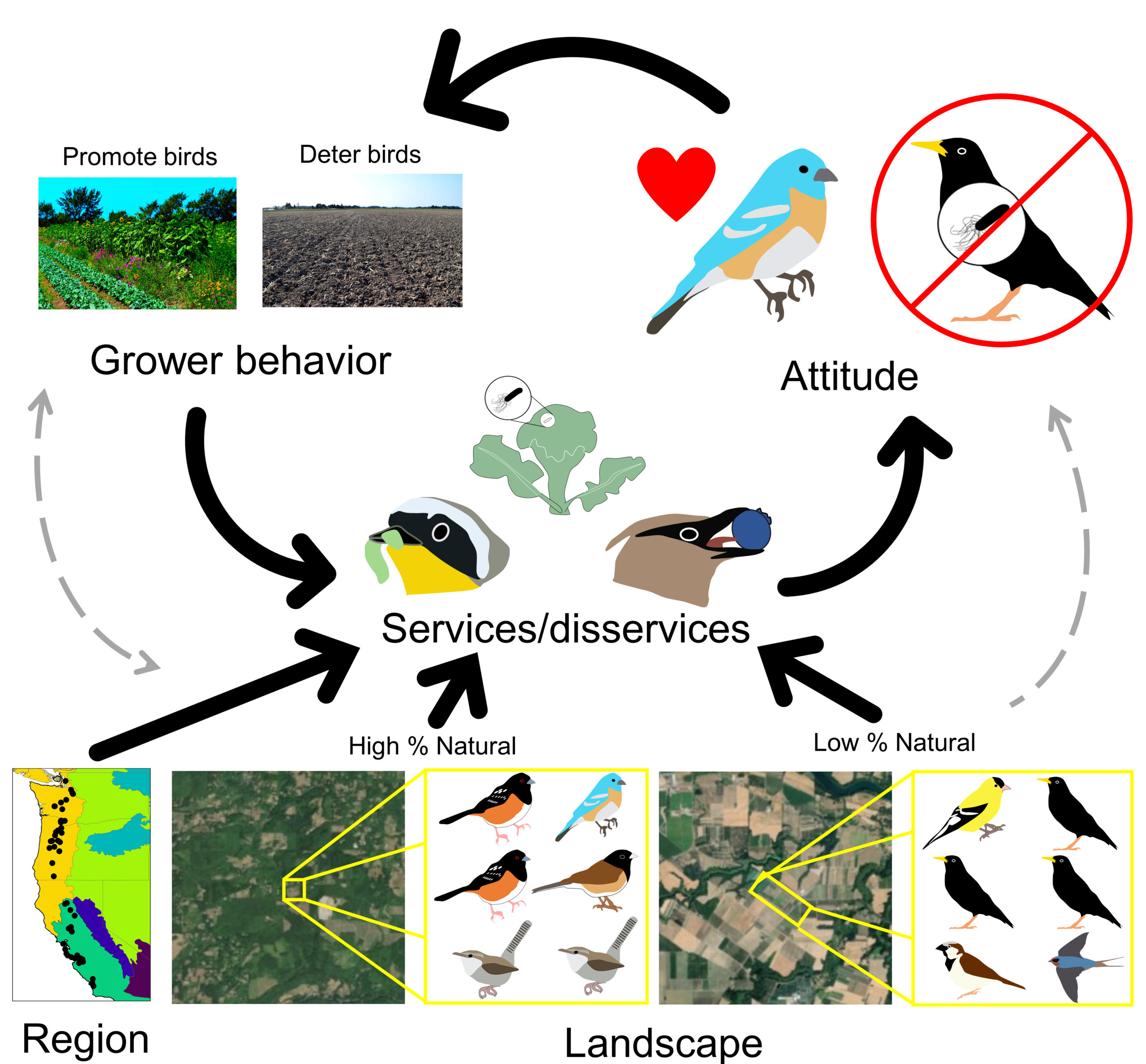

Understanding farmer attitudes towards birds and how that can lead to conservation can be complicated and filled with nuance. A new paper, co-authored by Nature Conservancy researchers and published in the journal Biological Conservation, is the first to empirically examine the full feedback loop linking growers’ attitudes toward birds to their management practices that promote ecosystem services by birds, which then reinforces grower attitudes.

“Ornithologists and conservationists assume birds provide ecological services, and that farmers want them on their farms,” says Olivia Smith, lead author of the paper. “But that’s not always the case.”

Smith adds that for farmland bird conservation programs to be successful, conservation programs have to provide clear benefits to farmers and align with their perspectives. The research sought to understand the feedback loops involved, which she says is crucial to increasing the adoption of and retention in bird conservation programs.

Perceiving Birds

To understand this feedback loop, researchers surveyed growers, counted the number and types of birds on farms, and documented on-farm management practices and the surrounding landscape to determine how attitudes about birds matched to conservation action on the ground. Over 50 farms were surveyed across two Bird Conservation Regions in the western United States.

Growers may be more likely to adopt conservation practices if they believe beneficial species are present. This may seem obvious, but context is important. For instance, nest boxes for bluebirds – a bird that eats crop pests and that many people enjoy seeing – might seem like a no-brainer. But those nest boxes could also be used by house sparrows, a non-native species that can cause significant crop damage.

“Non-native birds like starlings and house sparrows seem to be some of the worst species for food safety risks, which is of heightened concern in states like California, and these species are more common on farms surrounded by more degraded, less natural areas,” says Smith. “Farmers generally were cued-in-on the problems nonnative birds caused.” At the same time, conservation programs that promote more natural habitat at landscape scales, may promote more beneficial bird communities in farmlands that farmers want to retain.

So it’s not just the conservation practice that matters, but also the regional context, surrounding landscape, and habitat conditions.

The study found that growers generally exhibited more positive attitudes towards raptors than songbirds and allies like flycatchers, woodpeckers and hummingbirds. Farmers were especially favorable towards raptors in areas with large numbers of non-native birds. (In the farming area I mentioned earlier, quail are a non-native species, and raptors play a key role in dispersing them off the farm.)

Growers also held more positive attitudes towards songbirds and allies when they were embedded in more natural landscapes, primarily in the Northern Pacific Rainforest region where growers generally had more positive attitudes towards birds.

Getting farmers to incorporate conservation practices is often portrayed as straightforward: show farmers the benefits and results and they will change their behaviors. This research is important because it shows that an entire feedback loop has to be considered and that there are nuances involved. Carefully selecting farmers to target for conservation uptake can help promote birds in ways that will be beneficial to farmers and birds. It also allows conservationists to invest in farmland programs with the potential to achieve the greatest conservation outcomes.

“Our results suggest that conservation planning likely will be nuanced based on the environment farmers are farming in and if they have mostly pest or mostly beneficial birds,” says Smith. “Additionally, practices that have multiple benefits beyond just promoting birds will likely have better adoption.”

Editor’s note: Special thanks to Christina Kennedy and Olivia Smith for their contributions to this blog.

Join the Discussion