Last week, I posted a blog on the growing popularity of trail cameras and included a number of photos and videos of cool wildlife. I have received a number of comments and questions about one video in particular.

In it, a black bear walks down a path, with something large and rope-like trailing behind it. I have included it here for your viewing pleasure.

Many are disturbed to learn that this bear is passing a very large tapeworm. Is this rare? Will the bear be ok? How did it get the tapeworm?

It turns out, this happens more than you might think, especially in Alaskan bears. Let’s take a look at an aspect of the salmon ecosystem that you likely never considered.

The Circle of (Parasitic) Life

The camera trap video was captured on Alaska’s Prince of Wales Island by conservationist Michael Kampnich and its yuck factor has proven to be a big hit on trail camera social media groups. The bear is dragging what appears to be at least 6 feet of tapeworm. The bruin vigorously rubs its behind against a tree to unsuccessfully dislodge the parasite, then walks a bit more and gives a few shakes for good measure.

Donate Now to Protect Nature

Help protect threatened lands and waters around the globe.

It is not for the squeamish. But Kampnich tells me it’s not the first time he has seen bears with tapeworms of various sizes.

Alaskan bears – both black and grizzly – are particularly noted for tapeworms protruding out their butts. In fact, a quick YouTube search will show plenty of videos in this sub-genre. Viewers of live cam feed at Katmai National Park occasionally note giant worms dangling from the famous brown bears.

It’s not unusual for bears to harbor parasites. In this case, the tapeworm comes from the bears’ famous diet of salmon.

Naturalists know that Alaska’s salmon runs feed a rich and complex ecosystem. Bald eagles, bears, seals, gulls, wolves and more feast on the easy calories. Underwater, char and rainbow trout binge on eggs and chunks of decaying fish flesh. Salmon carcasses even nourish trees. It’s a spectacle of nourishment.

Now you can add the broad fish tapeworm to the spectacle. While this parasite may not make an appearance in the next nature documentary, it’s life cycle is pretty fascinating. Really, it is.

The tapeworm’s eggs are in Alaskan rivers, where they are eaten by crustaceans, which are eaten by salmon, which are eaten by bears. The tapeworm lodges in the bear’s digestive tract, where it lives out its days.

You know the saying about where the bear does its business? Well, yes, it does that in the woods. And also in the stream. And in doing so, it deposits eggs for the next cycle of tapeworms to begin.

The adult tapeworm gets its nourishment from what the bear eats. While bears can become lethargic and anemic, or lose weight, most bears manage just fine. After all, the tapeworm needs the bear more than the bear needs the tapeworm.

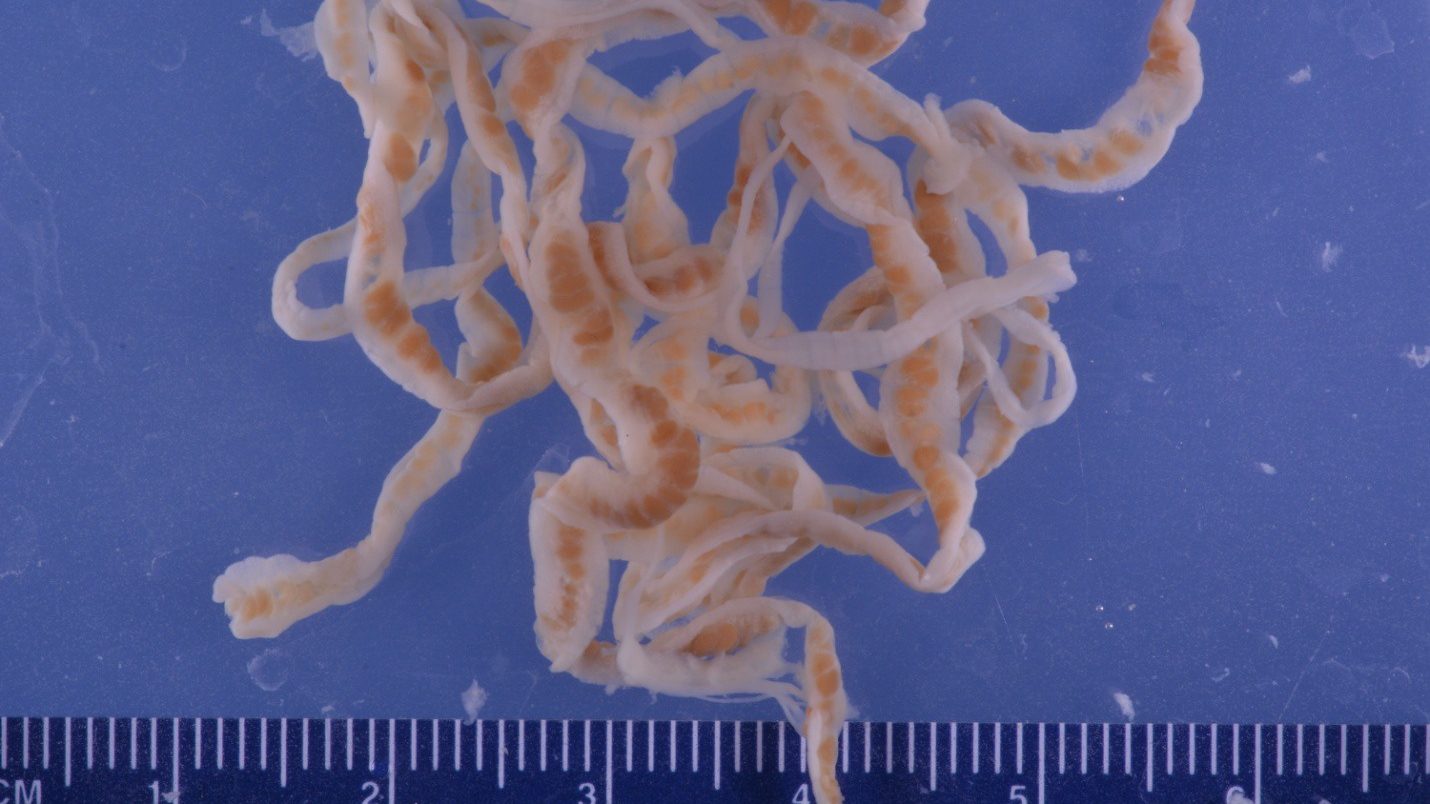

A tapeworm living inside a bear can reach lengths of 30 feet or more. Sometimes the bear defecates either a living or dead tapeworm. This appears to be uncomfortable for the bear, as you might well imagine.

It’s a Tapeworm’s World

There are at least 10,000 tapeworms on the planet, all with similar lifestyles and affecting numerous species. Including humans.

As with bears, most people will not even know they have tapeworms. Some will get sick and some will have an unpleasant surprise.

“The tapeworm is a monstrous and impressive creation. It has a segmented body, with male and female reproductive organs in each segment, so it is capable of self-fertilisation. It does not have a head as such—its “head” is only useful for holding on to its host’s gut, rather than for “eating” (it absorbs nutrients through its skin).”

The Guardian

The Guardian goes on to recount a pretty horrifying story where a man believes his intestines are falling out of him, which ruins his morning. He gives it a closer look. And then, like something out of Aliens, the “intestine” starts moving about of its own accord.

It turns out, this guy enjoyed a daily treat of salmon sashimi. And the popularity of sushi is increasing the cases of human tapeworms.

Apologies if this blog has altered your dinner plans.

Parasites are Biodiversity, Too

As much as we might not like this fact, parasites are a part of the earth’s biodiversity. If you can get by the gross factor, the evolution of these creatures is fascinating. And it’s not going away. An estimated 40 percent of animals are parasites.

It’s a tapeworm lodged in a bear’s intestine kind of world, a fact that most nature documentaries, wildlife photography and even conservation organizations tend to avoid. But it shows one of the reasons why camera trapping can be such a rewarding activity.

The camera trap captures all sorts of unusual behaviors and creatures. Including, sometimes, creatures we might wish we hadn’t seen. We might delight at bears playing, napping, and fighting. But parasites are a part of their lifestyle too. That may not be cause for celebration, but it can help us better understand wild animals and the complex ecosystems they inhabit.

Thanks for the article!

I have had the pleasure of flowing a Kodiak Bear on Afognak Island. It started to poo and a tapeworm came out and snagged on a bush. As the bear walked the worm pulled out and lay as strait as a tapeworm can, about 10 feet plus. Then other pieces down trail in 1 and 2 foot chunks, yes this article is accurate! I can only imagine the inner workings of a bears digestive system!

Honestly its completely turned me off. When i saw this capture it sent me screaming down the street…ok seriously, it really blew my mind. My auntie apparently had one, which resulted in my decision to quit eating meat. I simply couldnt wrap my head around the facts of its size & abilities and reflecting on said facts made this decision easy. Now one comment said a lab tech saw live worms in a sample & the client kept her worms inside her? Omg, that is too much. Im happy knowing I wont get this parasite ( dont tell me if im wrong ignorance is bliss)

Still another great and well put article Matthew!

OK Matt. You get the prize for the most unusual nature blog post I have ever read.

Keep at it!

Thank you Matthew for regaling the tape worm and parasite diversity. We need all the diversity we can get, from the bottom on up! No pun intended.

Poor bears–it’s gross, but totally logical. Parasites do need to switch hosts during their life cycles. I was the parasitology/microbiology department for a small hospital in the 1970’s, and one day we got a stool sample in which were some remarkably large tapeworm segments (the responses from the techs who received it running from “Yikes!” to “Omigod” to other exclamations). They were still alive, and under a low-power microscope we could watch the eggs squirt out. We sent them off to the state laboratory, since I couldn’t find it in the human parasitology references, and we didn’t have Internet yet; the report we got said it was from a large monkey tapeworm. The woman who harbored it said she’d been on a cruise to exotic ports but didn’t have a clue as to how (or when, or where) she had picked it up. When told it would be easy to kill it and get it out of her digestive system she declined on the grounds that it wasn’t bothering her. Okay…

Thank you for this very interesting and somewhat disturbing article!

How long does the tapeworm live in a bear and does it cause a lot of pain and discomfort for him/her?

Also, do you eat sashimi?