Imagine a turkey with a bright blue head, a rainbow of iridescent feathers and a tail display that reveals dozens of shimmering blue eyes. This hallucination of a bird is the ocellated turkey.

It is a tropical turkey, with a range that centers on the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico, Belize and Guatemala. Beyond its looks and tropical range, the ocellated turkey is otherwise similar to the North American wild turkey in its ecology and behavior.

Both species thrive in forested landscapes with interspersed farms, and both eat a wide variety of food items, including agricultural grains.

Like the wild turkey, the ocellated turkey’s efforts to raise young are fraught with the risk of predation from mammals, reptiles and other birds.

And both types of turkey have long been a sought-after prey of human hunters.

Our Thanksgiving holiday is based on a colonial origin-story in which a wild turkey is killed to feed hungry immigrants.

The wild turkey continued to provision Europeans as they proceeded to settle the Americas. But the pressure on these wild birds for human sustenance eventually became so great that they began to disappear.

Only intensive management to restore wild turkey populations brought them back from the brink of extinction.

Due to overhunting throughout the Yucatan, the ocellated turkey is now itself approaching this brink.

Ocellated Turkeys on the Brink

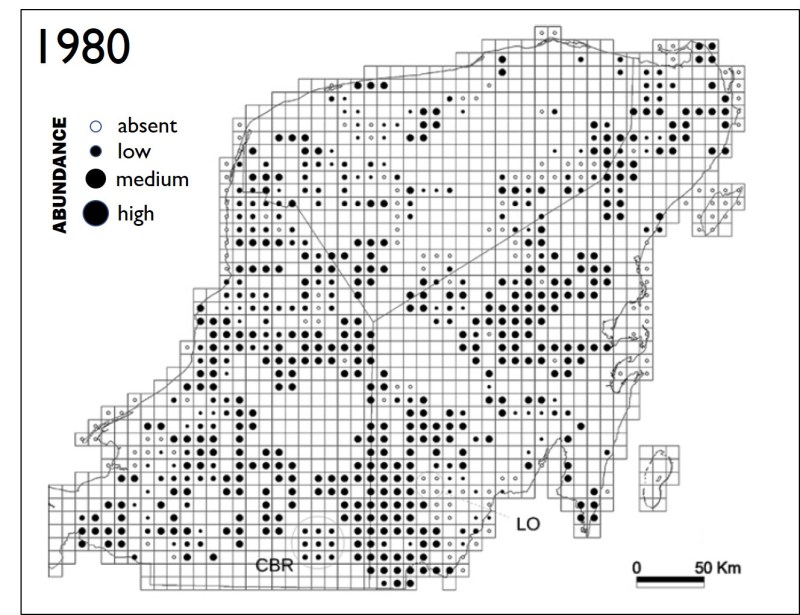

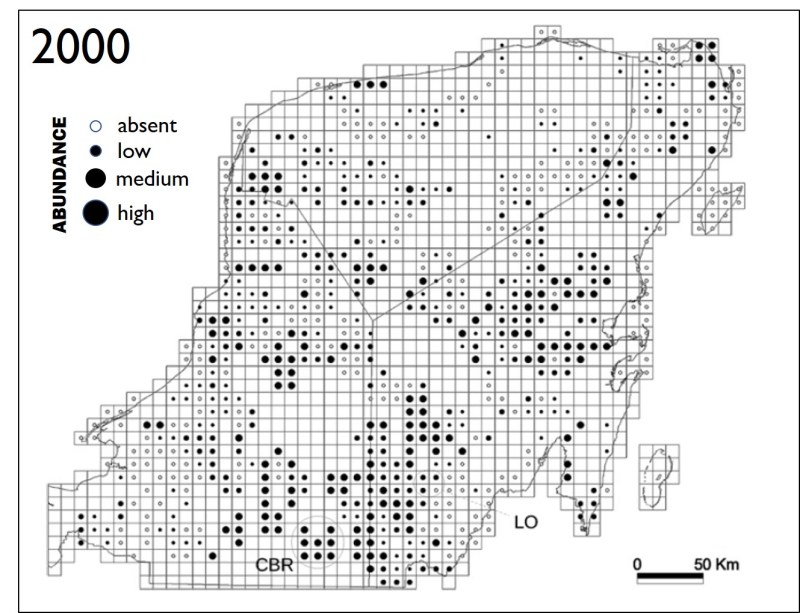

The limited information that exists on ocellated turkey populations tells us that there is a population decline and range contraction occurring with a current population of 20,000 to 50,000 birds. The only places where they aren’t declining are a few well-guarded protected areas.

The solution for halting this decline seems simple: stop killing them.

Because turkeys have high reproductive output and broad habitat preference, their populations would bounce back quickly if hunting were curtailed – just like the American wild turkey.

But the hunting pressure on ocellated turkey comes mainly from subsistence hunters – people who are not killing them for sport, but for a meal they can’t easily get elsewhere.

It was not long ago that the wild turkey in the United States was under similar pressures, and some people still remember these days. For example, my spouse’s grandfather spent his 1920s childhood in a mobile logging camp in Mississippi’s virgin longleaf pine forests. The logging operation would lay railroad tracks ahead of its path, inching the loggers and their families (who lived in rail cars) into the wilderness one woodlot at a time.

As they clearcut the habitat, they took the wildlife with them – wild game such as deer, turkey and quail supplemented the families’ diet.

Similar tales of deforestation and overhunting occurred throughout North America, and wildlife populations accordingly bottomed out.

By the mid-20th century, laws to curtail uncontrolled hunting had been enacted and were being fully enforced in the United States. But what truly allowed hunting to become a hobby, rather than a livelihood, were changing economic circumstances that gave most people the capacity to buy their meat rather than hunt it.

As a result, hunters could tolerate being regulated as wildlife managers worked to reintroduce turkeys.

The turkeys did the rest – their life history adapts them to rapid recovery when given the chance.

Now the ocellated turkey needs that chance in the Yucatan peninsula.

But the rub is, there is no economic sea change afoot that would easily allow recovery of overhunted Yucatan animals.

In fact, the ocellated turkey is under increasing pressure as human populations grow within the turkey’s range. People living in newer, smaller settlements are more likely to subsist on hunting. Research indicates that these settlements extirpate turkeys in a 15 km radius around them, leaving ocellated turkey populations fragmented and isolated.

Can Tourism Save Birds?

One conservation tool that can help arrest this downward population spiral, despite people’s dependence on wild game, is a program that has tourists from elsewhere pay for the privilege of hunting the ocellated turkey.

This approach has been tested successfully in community-managed forests in Guatemala’s Maya Biosphere Reserve.

It goes like this: communities that facilitate sport hunting programs get paid when hunters are successful. Such payments far outweigh the value of a turkey in the pot. As a result, fewer turkeys overall are hunted, and turkey populations in the region’s surrounding communities recover.

This type of program succeeds when there is a close relationship between the communities and the governments, nonprofits or businesses that market the program and bring tourists in for hunts. A necessary part of the program is monitoring to make sure wildlife populations are responding as expected.

Similar programs of tourists paying small communities for wildlife encounters have been established elsewhere in the world.

I participated as a tourist in one such venture in the Preah Vihear, Cambodia, where we went in search of the world’s largest and rarest ibis: the giant ibis. The Wildlife Conservation Society partnered with a village to host and guide birdwatchers in search of this near-mythical beast.

The giant ibis was thought extinct for more than fifty years before it was rediscovered. It has disappeared from most of its range in southeast Asia due to hunting and habitat loss. Now a population of less than 200 birds remains only in the remote and relatively undisturbed dry forest regions of northern Cambodia.

We were transported to the village by mopeds and ox-cart and stayed in an open-air dwelling built from rattan and thatch. We ate simple meals of fish and rice, smoky-tasting from wood fires.

At dawn we embarked for the ibis, hiking long distances across the savannah-like dry forest, our path stringing across a network of seasonal pools where the birds foraged for giant earthworms and frogs.

I confess that we never saw the ibis. It always stayed one step ahead of us that day as we followed its trumpeting calls through the forest.

I now learn as I read technical papers describing this program that we may have paid less because we didn’t see it. I hope not! I think part of our lack of success was that we were too noisy and our guides were too decorous to tell us so.

For both the giant ibis and ocellated turkey it might be unrealistic to expect tourism alone to be the engine for species recovery. Nonetheless, tourist programs can be an important catalyst for conservation, demonstrating to the people living with these species that these birds are both valued by the wider world and valuable to community members.

Tourist programs are but one element of a broader conservation playbook. It is still necessary to have population monitoring, enforceable regulations, protected area systems, controls on habitat loss and standards of living that prevent deforestation and overexploitation of wildlife. This, admittedly, is an awfully big agenda to pursue for the sake of a turkey.

With this intimidating agenda in mind, the prospects for ocellated turkey recovery may seem bleak. But the prospects for wild turkey in the United States seemed equally bleak 75 years ago.

The road ahead is difficult and uncertain but there is plenty of hope because we know that the ocellated turkey can bounce back rapidly under the right conditions, just like the wild turkey.

Why not allow a few pairs taken to zoos and into breeding programs to insure they do not go extinct?

When will man (men and women) discover that raping the earth is a terrible thing? The plight of mammals, sea creatures and birds will be the plight of mankind one day. The native population of areas were very good stewards. They only killed what they needed to survive, and made use of every part of that creature. Native Americans, Indians, were great examples. The Europeans came in and decimated the Indian population and, over hunted as many animals and birds as they wanted. The American Indians were so deceived by the American government, I am ashamed, of course I didn’t live back then, but even if I had, what could I have done about it? Women’s hats needed feathers, animal pelts were needed for one to make a living. So, just go ahead and extinct so many creatures. Europeans already used up trees in Europe, and who knows how many creatures? Man’s greed will surely be man’s extinction. The problem is that not enough people with enough money can stop it. I am so sad to think, how many land and sea creatures will my grandchildren be able to see in the wild? When will we learn that overpopulation of humans, and man’s greed will become our undoing? People like Al Gore preach about man’s carbon footprint, how big is your carbon footprint, Al? Just one of thousands for an example. Wake up mankind, it’s almost too late.

Enjoyed your piece. I worked on the collated Turkey project in Guatemala w Lovett Williams.