What goes down April 12, 2017 on a Sanibel, Florida beach is both encouraging and discouraging.

Angler and shark tagger Elliot Sudal hooks something huge. A crowd gathers including Vice President Mike Pence accompanied by his entourage of Secret Service agents who rifle through Sudal’s tackle box. Not surprisingly, they find (and temporarily confiscate) knives. But Sudal, seated and straining on the rod with blistered hands, is hardly a threat. Pence safely takes photos, then poses for a photo next to the embattled Sudal.

After 11 hours a 13-foot smalltooth sawfish writhes in the wash. Two onlookers fasten a rope to the tail and haul it thrashing onto the sand. Sudal inserts a shark tag, measures the fish and cuts the line. A video of the fight goes viral, garnering thousands of “likes.” Wink News identifies the animal as a “sawfish shark.”

There’s no such thing; sawfish are highly modified rays.

What was discouraging is the public ignorance behind such Endangered Species Act (ESA) violations. “These kinds of encounters are frustrating for us,” declares smalltooth sawfish recovery-team member Sonja Fordham, president of Shark Advocates International and who, while at the Ocean Conservancy, cowrote the petition for endangered status. “Only a handful of people are permitted to tag sawfish. This person wasn’t. We can’t have the public doing this stuff. You need to release sawfish right away. You can’t drag them around or take them out of the water.”

And this from recovery-team member George Burgess of the Florida Museum of Natural History: “We record every sawfish capture, sighting or encounter everywhere in the world. There are still guys doing nasty things to sawfish. I blame elevated testosterone. We tell them it could cost them $10,000.”

And this from recovery-team member George Burgess of the Florida Museum of Natural History: “We record every sawfish capture, sighting or encounter everywhere in the world. There are still guys doing nasty things to sawfish. I blame elevated testosterone. We tell them it could cost them $10,000.”

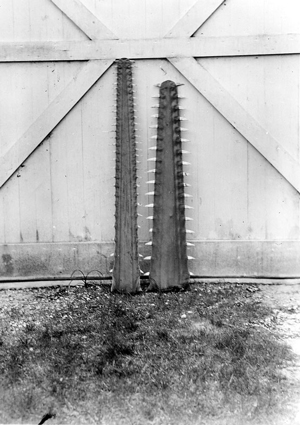

The National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) won’t take any action against him or his assistants. The agency is more concerned about illegal traffic in sawfish parts, usually rostra (saws). Fordham and her fellow recovery-team member Tonya Wiley, president of Havenworth Coastal Conservation, monitor auction and sale sites that offer sawfish parts; eBay pulls the illegal, post-listing ads.

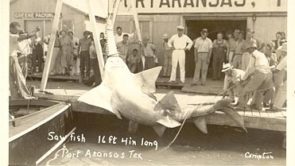

What was encouraging is that the sawfish was there; the population is down by an estimated 95 percent. The species, which can grow to 17 feet, once occurred from New York to Texas. Now its U.S. range is restricted mostly to southwest Florida (the original core area), though there has been some recent expansion west and along the East Coast.

In 2003 it became our first native marine fish listed as ESA endangered. The largetooth sawfish, once globally distributed, has not been seen in U.S. waters since 1961. Three other sawfishes — dwarf, knifetooth, and green — inhabit the Indo-Pacific region. All five species are listed as endangered by the U.S. and the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species.

Close Encounters of the Sawfish Kind

The smalltooth sawfish had nearly vanished from the U.S. when research for recovery started in 2001. “It was shocking how little we knew,” says Wiley. “We had no idea how fast they grow, how many young they have or how often they reproduce.”

The recovery plan predicted that delisting wouldn’t happen for 100 years and then only “if all recovery actions are fully funded and implemented.” But smalltooth sawfish mature faster than previously thought — probably at about seven years of age. They deliver dog-size litters every other year. “I think we were originally too pessimistic,” says Burgess. “Fifty or sixty years might be more likely for recovery.” The plan is being updated.

Smalltooth sawfish numbers are increasing mainly due to ESA and state protections and Florida’s 1995 net ban, which saved sawfish from dying as bycatch when their rostra are entangled in gill nets.

And as sawfish numbers increase encounters like Sudal’s increase with them. So sawfish advocates are rushing to educate the public. “The first step,” says NMFS’s Adam Brame, sawfish recovery coordinator, “is to make people aware that sawfish exist. The second is to tell them what to do if they see or catch one. We erect billboards and make public-service radio announcements. We distribute sunglass straps and marine key chains with the phone number to report encounters (844-472-9347); and we have laminated cards with safe-release guidance that we hand out at fishing trade shows. At these shows we talk to fishermen and let them know we’re not trying to close their fishing areas and that their reports help us meet recovery goals.”

As NMFS instructs: It’s illegal to purposefully fish for, kill, injure, harm, remove from the water or otherwise harass a sawfish. If you accidentally catch one, cut the line near the hook and avoid the flailing rostrum which can inflict serious injury. Take a photo if possible, fill out and submit the sawfish encounter form, and call the international sawfish report number (352-392-2360) as well as the one above.

“Lots of people mishandle sawfish, but documented killings are rare now,” says recovery-team member Dr. Dean Grubbs, elasmobranch ecologist at Florida State University’s Coastal and Marine Laboratory. “Occasionally we find sawfish with their rostra removed. They’re usually in bad shape, and they inevitably die.”

So oblivious is the public to the plight of sawfish that advocates are desperate for any kind of publicity. They’ve even asked Disney for an animated film in which a talking sawfish is the next “Nemo.” And the Discovery Channel’s July 28th Shark Week feature “The Lair of the Sawfish,” which accurately described the smalltooth sawfish as “endangered,” elicited muted applause from most recovery-team members.

Unfortunately, the show went on to proclaim that the species is “one of the world’s deadliest predators” and that in order to find it researchers must “go deep into the abyss and be willing to pay the ultimate price.” Sawfish don’t have “lairs”; they spend most of their lives in shallow mangrove flats; and one would have to scour the seven seas to find fish less aggressive to humans. Burgess, formerly a regular on Shark Week because he directs the International Shark Attack File, denounces this and other Shark Week shows as “godawful hype and baloney.”

Hope for Sawfish

Grubbs did not “pay the ultimate price” or descend into the “abyss” on what he calls “probably the most exciting research day of my life.” That was December 7, 2016. He and his team caught a 14-foot smalltooth sawfish on the west side of Andros Island, biggest of the Bahamas.

As they were inserting a tag, they noticed two rostra protruding from her vent. She was giving birth — as far as can be determined, something no human had previously witnessed. They assisted her in delivering five healthy pups (https://www.azula.com/first-sawfish-birth-filmed-wild-2476381732.html).

While sawfish are not specifically protected in the Bahamas, Andros is a stronghold because the west side was designated a National Park in 2002. But land there has recently been sold for agriculture. One of the main reasons sawfish chose the west side is because extensive freshwater from Lake Forsyth gives them a competitive advantage over sharks that share their backcountry niche. “If the lake gets dewatered for agriculture, that could have huge implications,” notes Grubbs.

All sawfish everywhere are ESA-listed as endangered, but when Grubbs and his team first went to Andros in 2010 endangered status for smalltooths applied only to a U.S. “distinct population segment.” The mission was to determine if there was exchange between American and Bahamian sawfish. “We’ve tagged seven at Andros and 60 plus in Florida, and so far none has crossed over either way,” says Grubbs.

But there might have been exchange between Florida and Gulf states to the west. DNA from old rostra displayed in restaurants and tackle shops could determine that, so the recovery team is asking the public to report locations of old rostra by calling 844-472-9347. Scientists will take a tiny sample from inside the rostrum so nothing shows. This information is important because sawfish recovery depends on populations being large and genetically diverse enough to adapt to environmental changes, resist disease and avoid inbreeding. If genetic diversity in contemporary and historic populations is similar, survival outlook may be good and recovery can focus more on habitat restoration and protection.

While the U.S. leads the world in sawfish recovery, its single sawfish, the smalltooth, is restricted to the Atlantic, Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico — smallest range of the five species. The others face dimmer futures. While Australia takes good care of all four of its species, developing nations pay scant attention. And the demand for sawfish fins for soup far surpasses demand for shark fins. “I don’t think people believe sawfish fins taste better or make them more sexually adept,” says Burgess who recently returned from Indonesia where he and colleagues searched for sawfish and spread the word about the need to save them. “I think it’s more a status thing — ‘Hey, I can afford to eat and serve sawfish fins.’”

If you don’t encounter a sawfish or don’t know of any old rostra, you can still help. Shark Advocates International’s Fordham offers this: “I used to say, ‘Tell your members of Congress to fully fund the sawfish recovery plan.’ But with the current state of our politics some people just laugh at that. Now I start with: ‘Tell your members of Congress not to gut the ESA.’”

America is a beacon of hope for sawfish all over the world. If we lose the ESA, that hope will fade away and, with it, all manner of fish and wildlife — remnant sawfish populations included.

Thank you to the dedicated people who are working to help the sawfish, through research, public education, journalism, law enforcement, conservation work, and every other way. You are beacons of hope to me.

Liked the Article