What are the wild origins of our domestic turkey – and who did the domesticating? It’s a remarkable story, and one that doesn’t have anything to do with Pilgrims.

It was, of course, Native Americans who domesticated the wild turkey. Thanks to archaeology and genetics, we have a fairly clear picture of where our Thanksgiving turkey has come from.

Based on what is known so far, the birds were independently domesticated twice, in different places. The Anasazi domesticated turkeys in the Four Corners region of the southwest United States, and the Aztecs (and their forbearers) did the same in southern Mexico.

Domestication occurred more than 2,000 years ago; turkeys were penned up and used for their feathers, bones and meat. Taming the turkey came about in places where people were permanently settled and had ready availability of grains to feed the captive flocks.

Carbon isotope analysis of turkey bones found at archaeological sites shows that the diets of these domestic birds were primarily corn-based, as compared to a wild bird’s broader palate.

Free food seems to take the “wild” out of turkey pretty quickly.

If you happen to have a wild turkey flock that visits your bird feeder, you can imagine that it wouldn’t be a great challenge to domesticate a new suburban breed of turkeys.

The South Mexican Wild Turkey

As I was reading about the deep roots of our dinner table turkeys, I came across references to the “south Mexican” wild turkey. It turns out that this is an enigmatic sixth subspecies, also known by the Aztec name for turkey, guajolote.

The list of turkey subspecies is usually limited to five: Eastern, Merriam’s, Rio Grande, Osceola and Gould’s.

A sixth subspecies is rarely noted. In any sources I read, if this sixth species was discussed, it was only briefly. Some references mention it being critically endangered, while others conclude that it is already extinct.

eBird reports some sightings in mountainous areas within the bird’s former range, but these could be domestic birds or reintroductions of other subspecies.

The South Mexican subspecies is ghost-like, with its spirit perhaps now only inhabiting the genes of our plump, white barnyard fowl.

That’s the conclusion of a landmark genetic study from 2010 that definitively sorted out the origins of domesticated turkey lineages.

All of our modern-day domestic turkeys originate from the tamed Aztec birds from southern Mexico. And the wild progenitor of these birds was the sixth “South Mexican” subspecies.

Anasazi-bred domestic turkeys from the Four Corners region had their roots in the Eastern and Rio Grande subspecies. Today there is no trace left of this second domestic breed. It was once thought that the Merriam’s subspecies might be a feral form of the Anasazi domestic breed, but the genetic evidence doesn’t support this idea.

It was via Spanish contact that the Aztec birds then made their way to Europe to further proliferate as a domesticated animal. The barnyard turkey then made its way back to North America, now traveling with European colonists.

The domestic turkey then, has its deepest roots in the Mexican culinary tradition. Fortunately, a 16th century Franciscan monk, Bernardino de Sahagún, gave us a sense of what turkey recipes were like. He conveys countless details of Aztec culture, in his 12-volume series known as the Florentine Codex. The work was a close collaboration with the Aztecs, including more than 2,000 illustrations drawn by them.

In his book A History of Food in 100 Recipes, William Sitwell compiles Bernardino de Sahagún’s culinary accounts of turkey. The Aztecs served turkey boiled and roasted; stewed with corn; accompanied by mole-like sauces; and as a tamale filling. The friar really enjoyed his turkey, writing – as covered in Sitwell’s book — that it was “always tasty, savory and of very pleasing odor.”

There are plenty of domestic turkeys still in Mexico, lurking in barnyards and provisioning tamales, but what became of the wild South Mexican subspecies that begat all of this deliciousness?

It seems that they were very scarce by early 20th century.

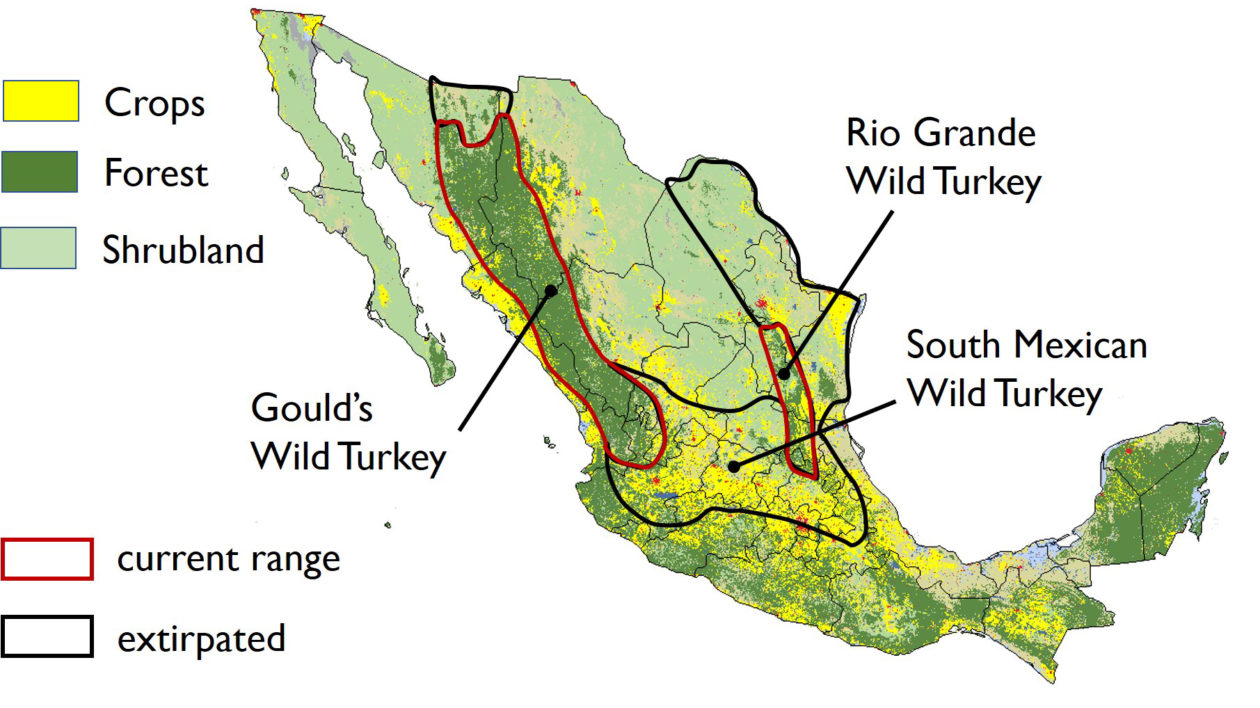

In his 1959 book about Mexican wildlife, preeminent ecologist Aldo Leopold shows a blank spot in the part of the range where the south Mexican turkey ought to be.

His maps reflect the range of the Gould’s subspecies (to the west) and the Rio Grande subspecies (in the east), but nothing in the south-central region of Mexico.

Leopold gave careful consideration to all current and historical records that he could find, indicating to me that this sixth subspecies had already been missing for quite a while. After Leopold’s book, subsequent authors fleshed out the original range of the South Mexican subspecies to span across south-central Mexico.

We know that other turkey subspecies were once beleaguered, having been hunted out in many places. Wild turkeys are abundant today only because of careful management of hunting along with reintroduction programs. So it may stand to reason that the south Mexican turkey was simply hunted out by Native Americans, conquistadors and their descendants.

But another important factor may be habitat loss. Examining Mexico’s present day landcover, it is clear that the former range of the South Mexican wild turkey is occupied by widespread agriculture. Where there are no trees, there are no turkeys. So habitat loss also likely has played a role in the disappearance of the wild guajolote.

Apparently gone from the wild, the 6th turkey subspecies nonetheless lives on in the form of the domestic turkey. This Thanksgiving, let’s offer thanks to the Aztecs for giving the world one of its favorite fowl.

If you want to bring Thanksgiving closer to the domestic turkey’s ancestral home this year, here’s a link to a whole list of Aztec-inspired recipes, courtesy of art historian and chef Maite Gomez-Rejon, including Pozole de Pavo: turkey and Hominy Stew.

Tamed or captive wild flocks aren’t domesticated. Domesticated animals can’t survive without human intervention. The same standard should apply as in Africa. There were false claims of the first cattle domestication occurring in southern Egypt or North Sudan. Turns out they were capturing and penning aurochs/wild cattle. There has to be selective breeding.

I guess Ocellated Turkey Played no part?