The mention of bison roaming conjures images of specific places: Yellowstone and the Badlands, the Great Plains and prairie preserves. The wide-open spaces of North America, past and present. But Europe? Chances are, your mind does not connect bison and Europe.

But yes, there are bison in Europe. In fact, story of the European bison’s rescue may be even more dramatic and more perilous than the more well-known saga of the North American bison’s near-miss with extinction.

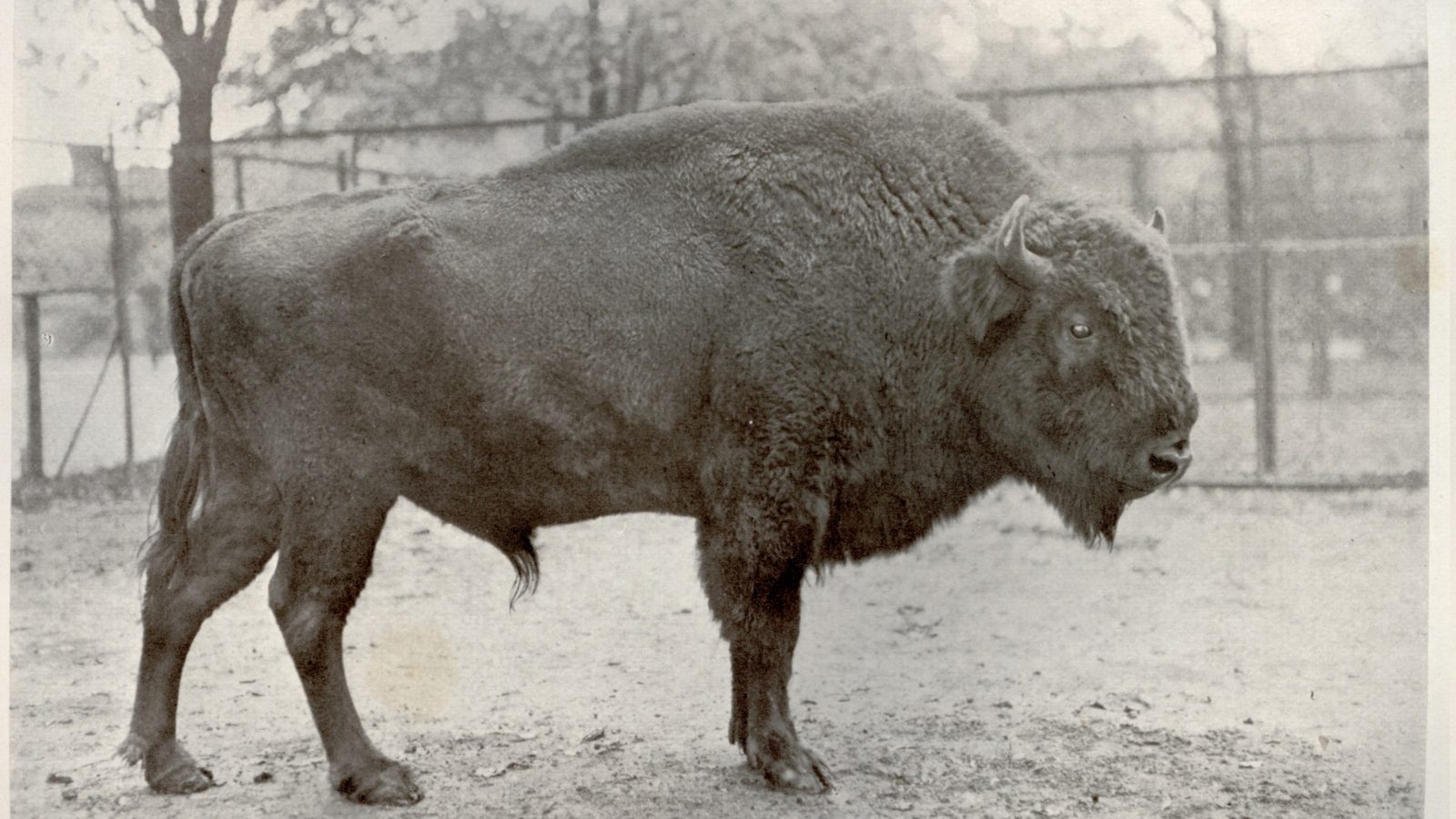

The European bison, or wisent, resembles the North American bison, but it’s not as shaggy, has a lankier appearance and has curved horns that bring to mind domestic cows. There is a lot about the species we don’t know. By the time scientists and naturalists began studying it, only 50 or so animals remained in the world. As such, biologists had only an incomplete picture: they were studying the survivors, the most adaptable of the species clinging on in remote refuges.

As such, there’s a lot of missing information on the wisent’s natural history, habits and habitat. But growing interest in the animal in recent years has offered new understandings about the European bison’s past – and could help shape a hopeful future for Europe’s largest remaining land mammal.

European Bison Under Siege

As the famous cave paintings attest, large herds of wild mammals once roamed Europe. But human settlement and agriculture displaced or eliminated many of these species. Humans pushed European bison to the few remaining patches of wilderness on the continent.

By the 20th century, against long odds, two populations still survived. One, in the remote Northern Caucasus Mountains of Russia, contained only a small number of individuals. A more viable population survived in Poland’s Białowieża Forest, a long-time protected reserve. In the mid-16th century, a Polish king instituted the death penalty for poaching a bison; restrictive laws remained in place with succeeding rulers.

This actually didn’t stop poaching, but a relatively large herd of some 600 bison remained. But when there is a single, isolated population of a species, it makes it highly vulnerable to threats. A single calamity can change the fate of the species. This is a recurring theme in conservation science. It nearly spelled doom for the wisent.

In World War I, occupying Germans took the Białowieża Forest. A scientist apparently informed officers that the bison in the forest were exceedingly rare, but it didn’t matter. Soldiers shot them for meat and because they were there to shoot. As they retreated out of the forest at the end of the war, they shot more.

Only nine animals remained.

The survivors were gathered and placed in zoos. In 1927, the Caucasus population of European bison disappeared; the remaining global population at that point consisted of a dozen animals.

Rescue and Resurgence

Numbers grew slightly; with so few animals, the need to manage breeding became apparent. Documenting each individual and its lineage began in 1923 and resulted in the European Bison Pedigree Book being published in 1932. It’s been published every year since, and documents every living wisent. This was the precursor to what is now standard procedure for zoos in breeding and managing endangered species.

The Białowieża Forest remained a viable reserve: large and undeveloped, it was one of the few areas of “wilderness” in Europe. European bison returned there relatively quickly. By 1928, a special breeding project was set up in the forest. In 1952, two bison were released into the forest, back in the wild at last.

Today, Białowieża is home to nearly 600 European bison. But overall, the species has recovered slowly. This was in large part because much of the population is found in zoos. With limited space, zoos simply can’t accommodate large herds.

In 2000, about 2,800 European bison survived. That’s fewer than the number of American bison living in Yellowstone National Park (the total population of American bison exceeds 500,000 individuals). The European bison still seemed to face a precarious future, but new interest in this animal charts a hopeful path forward.

Rewilding – the return of large, native wildlife to restored and connected wild spaces – is a controversial idea in North America. In Europe, though, the idea has attracted more enthusiasm and support. Europe, with a large human population and little wilderness, may seem an unlikely bet for rewilding. But many proponents argue that even small nature reserves can be home to large wildlife. Like bison.

Conservationists argue that mammals like European bison play a significant role in shaping ecosystems. Much as American bison have played a role in grassland management on Nature Conservancy preserves in North America, European bison are now shaping forests and open areas in Germany, France, Spain and other countries.

European bison can thus be seen in some places where they’ve been gone for centuries, like the Netherlands’ Kraansvlak reserve. Celebrating ten years since reintroduction, Kraansvlak now draws thousands of tourists to see the animals, and are demonstrating to ecologists how they graze on the grassy habitats next to sand dunes.

With room to roam and breed freely, the European bison herd has increased to more than 6,000 animals. More reserves are proposed for reintroductions every year.

The interest in European bison has also led to more research. A recent paper in Nature uses genetic markers to establish the lineage of this species. As Emma Marris writes, researchers found that European bison are actually a hybrid of the steppe bison, the Eurasian ancestor of American bison, and aurochs, the ancestor of domestic cattle. Both species are long extinct, but the European bison survived. Marris notes that researchers gleaned clues about the species’ history by examining cave art. While this too is contested scientific territory, it appears that the wisent was better able to withstand humanity than either of its ancestors.

Today, European bison are associated with old-growth forests, due to their relative abundance at Białowieża. But it’s important to keep in mind that Białowieża’s herd consisted of animals forced into the last remaining wilderness to survive. Many experts believe the bison’s preferred habitat is open grassland next to forest. This, too, is subject to debate, especially as Poland considers logging Białowieża. Some believe this will drive bison away, while others believe it will benefit the animal.

In any case, reintroductions to more open habitats will likely show that bison are not primarily a forest creature.

Rewilding has many critics who see it as hopelessly nostalgic and a waste of money. Many point out that Europe is not going to return to the Pleistocene and that reintroducing bison to a small nature preserve is a hopeless stunt.

But as Yvonne Kemp points out in her lovely essay on the bison of Kraansvlak, perhaps rewilding is not about looking at the past at all, but a new way of people and wildlife living together in Europe. For millennia, Europeans competed with large wildlife. Now, they can find ways to coexist, and to have encounters with large, magnificent beasts as part of their lives.

“The bottom line is: if we can make such a project a success in the tiny, crowded country of the Netherlands, then we should definitely be able to boost bison numbers in more areas where it historically once roamed,” Kemp writes.

I find it inspiring that even in crowded Europe, the big beasts can return. That in nature reserves in France or the Netherlands, a young naturalist may look over a grassy knoll and come face to face with a Pleistocene beast. It’s not a glimpse into the past, but a vision into a vibrant future.

Amazing. I thought they were extinct.

Hi Mathew, my father was born in Eremichi Belarus on the Neman River close to the Bialowieza (White Forest). He spoke often of the Zubr. Your expose has helped me understand his love of the Belarusian National Animal and the dire consequences of human development affecting this large Beast.

Regards AlexB

Hi Alex,

Thanks for sharing. I would love to go Bialowieza and look for the wisent some day. It indeed looks like a beautiful forest.

Best,

Matt

I did not know there were European bison. I was heartened to hear conservation efforts go so far back and have met with, perhaps, limited, but documented success. Yes, a little lighter than the American buffalo, but definitely recognizable. Thank you for your efforts.

Awesome article Matthew. It is great that there are more people out there with the foresight to save what is in effect, our heritage, for future generations. As a South African ex-field guide I can appreciate the feeling of euphoria of being in a nature area with loads of large wild animals. The anticipation for me seeing a pack of Wild Dogs or a Leopard was incredible. Here is the Netherlands we are seeing the Wolf returning, Wisent being re-introduced, Golden Jackal spotted … very exciting times. Conservationists and scientists must manage these matters with upmost care to ensure that the general population have a positive feeling about what is happening. Farmers will have to be appropriately compensated for loses due to predators. However, I believe it critical for youngsters to be educated as to the value of nature and getting out into nature and away from their electronic gadgets. All the best.