My son returns from the gravel bar and says it will do as a camping site. “Just watch out for the pile of dog poop,” he says.

We’re on the final day of a three-day river trip, and this location seems an unlikely location for dogs. I ask my young outdoorsman to show me the poop. He runs to the edge of the willows, about five feet from the waterline, and squats low for close inspection. I do the same. He’s right. It’s poop. But not from a dog.

It belongs to a bear. I can tell because it’s purple in hue and full of berries. Bears bulk up on berries and while I have no interest in picking up the pile, a greenhouse manager in Colorado does. Right about the time I pass on the pile in my camp, she’s collecting one in Rocky Mountain National Park.

“I was pretty excited when I saw the volume of seed in the scat,” says Trish Stockton, Rocky Mountain National Park biological science technician. “It filled a small Ziploc bag a bit bigger than sandwich size and we didn’t touch it.”

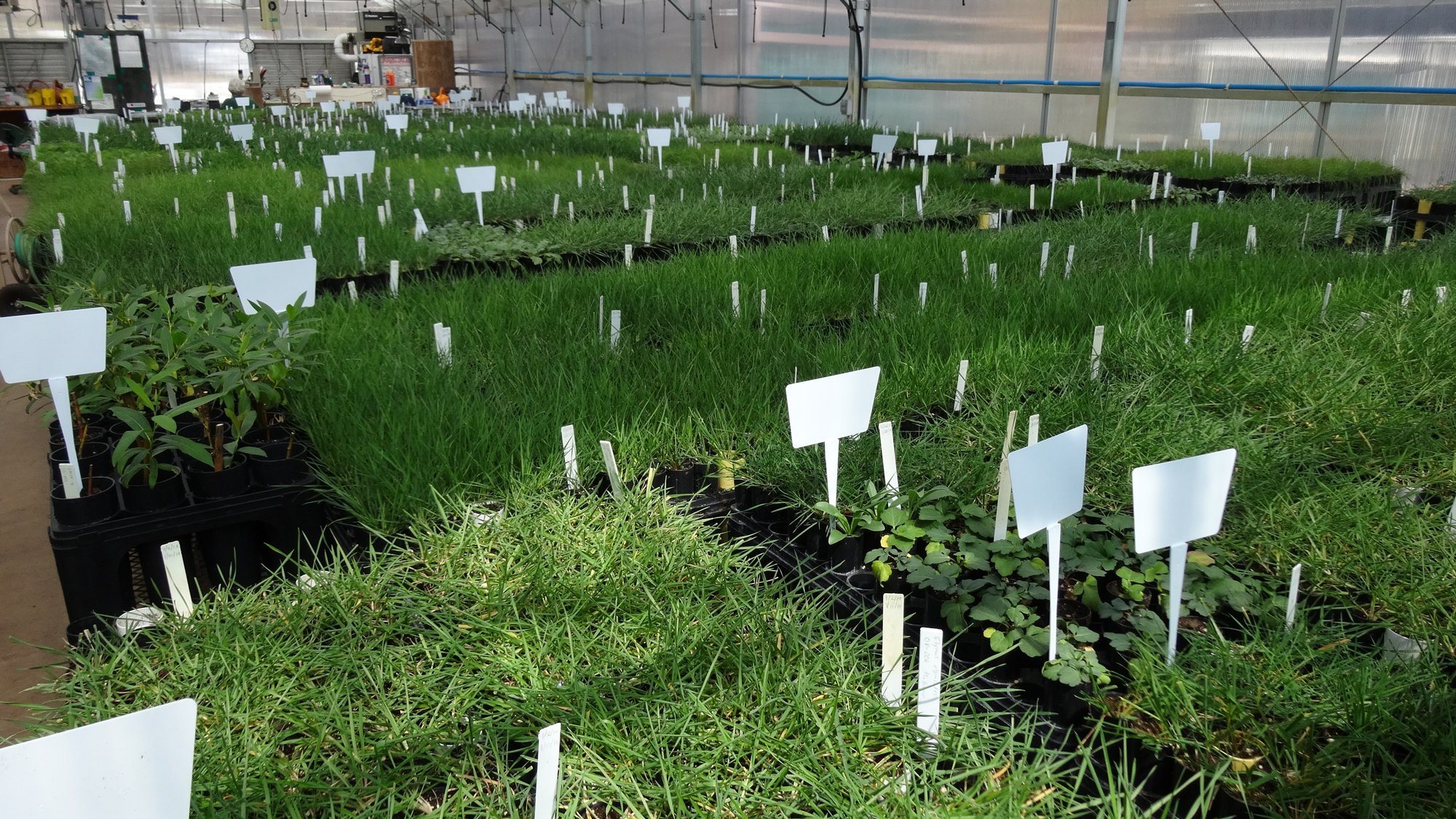

She didn’t have to. The dried sample went directly into greenhouse soil at Rocky Mountain National Park where 30,000 to 50,000 plants grow annually. Those plants are distributed among restoration projects within the park: often disturbed sites like construction zones where roads are widened and waterlines are replaced.

“If we don’t have somewhat well established plants that we’re putting in the ground, all it takes is a couple of footsteps and the young guys are trampled and killed,” says Kevin Gaalaas, Rocky Mountain National Park supervisory biologist.

Stockton’s one sample of bear scat from last fall sprouted 1,200 seedlings this spring. Now the greenhouse is, well, green, because of one pile of purple poop full of berry seeds. Mostly Oregon grape with some chokecherry chewed in for variety.

“It’s not the first pile of poop that has been brought to me, I gotta tell ya,” Stockton says. “This is my third try. Other piles I collected over the years didn’t have such a large volume of seed in them. To find a pile with that many seeds in it, I knew I was on my way.”

Adding to the excitement is the human labor scat saves. Woody plants, like chokecherry, are hard for people to germinate. Nature is better at it. Park staff tries to mimic natural germination by soaking seeds in acid baths, but it doesn’t work nearly as well as a bear’s stomach.

And Gaalaas estimates it would take 100 human hours to collect enough seeds to match what’s in the one sample of scat that took a few minutes to bag up, bring in and dump in the dirt.

“We’ve tried to grow these before and it took a lot of effort,” Gaalaas says. “This by far took a lot less effort and got more results than ever before. Sometimes mother nature does a heck of a better job than we do.”

The scat seedlings, which are twice as tall as any human-grown sprout, are not an official scientific study with volumes of data and hours of research. They’re unofficial and called pocket science. This mini-experiment produced the kind of results that make adding real science motivating.

“If we know what’s at seed and when bears will be eating that plant, we could go out at certain times of year for scat with a little guess work,” Gaalaas says. “You have success every once in a while and find a more efficient or better way of going about things. That’s the stuff that makes our day.”

The plants popping out of poop will be distributed throughout the park this summer with the other new plants, grasses and tree starts in the greenhouse. All of them raised with no pesticides, minimum fertilizer and little water. They’re natives so even if they sprout in the greenhouse, they still have to make it in a park that doesn’t have mercy for the weak of limb.

“Rocky Mountain species are well adapted to soils not high in nutrients naturally,” Gaalaas says. “We’re growing for dry climate. They can handle temperature swings. They’re adapted to cold nights, hot days and high elevation.”

Some of the new berry bushes will return to where the scat was found. Maybe one of the park’s other two dozen black bears will come looking for another snack.

Other plants will re-green construction where a waterline was replaced. They’ll naturally improve the view for 4.5 million annual visitors. At least some of those visitors will most likely have some scat questions for Stockton. She can’t wait.

“I’m getting a lot of questions like, what will come out of deer poop or elk poop? I say, ‘Nothing. They don’t eat berries,’” Stockton says. “It’s opened up a conversation for sure. That’s wonderful. I’m totally into what I’m doing and when I get anybody interested in what I’m doing and they let me talk for five minutes, I’m thrilled.”

And I’m intrigued. A plastic bag for bear scat is going on my next river trip. I’d like some chokecherries in my backyard.

A fantastic article!

https://www.frontiersin.org/research-topics/17497/animal-seed-dispersal-an-ecosystem-service-in-crisis#articles

Thank you!

Gordon

Gordon W. Schuett, Ph.D.

Hello, I live in Oakland CA. I was hiking in the hills among our rare Pallid Manzanita. It has been my understanding that people have not been able to propagate this rare species except by cloning which is not a healthy viable method. It occurred to me while hiking that perhaps Pallida is reliant upon bears eating and pooping seeds to propagate. So, I googled it and found you! Obviously we no longer have bears here but we used to even have Grissly bears. Do you know if anyone has explored this as a method of propagating this species?

thank you for your work,

Vicki

This was good

Great story…but please honor the inspiration with which you’ve written. Don’t encourage overpopulated Homo Sapians, all collecting bear poop out of its natural location, unless it is part of a dedicated Sustainability Project, like the one you written about here.

The Other Bears Need that Poop to stay in the “Cycle of Life” and create more berry bushes. Not for your backyard, dear friend and beautiful writer of this article, but for the Miraculous “Web of Life” that you pay such beautiful Homage to here.

Please “Keep the Poop on the Ground!” unless for beautiful Conservation efforts.

It’s not meant for your backyard or the other100s of readers with backyards,

enjoying this great article. Leave those ziplocks behind, please!

en L’akesh,

Suzanne

Here in the highlands of Costa Rica I often find coyote scat with Higuillo seeds, a kid of Ficus.

Have just read that chimpanzees helped to expand the range of various food plants in African rain forests through their scat… If only humans would increase their efforts to propagate more polycultures and less and smaller monoculture.Next time that I go for a walk in bear territory must take a few good sized Ziploc bags for such samples of scat, interesting that the germination is improved…

Our house is close to the Dolly Sods Wilderness area that is covered with wild blueberries. We’ve learned to live with the bears or rather they’ve learned to live with us. One female was a frequent visitor that my husband talked to and he photographed more than 25 of her cubs over a 20 year period. Although they were close by, we never had blueberries and Jim thought he’d gather up the purple scat and transplant it. Over several midsummer weeks, he’d pick up the piles with a shovel and carry it to an area he’d prepared. We never tried to get closer to her than she would to us but we watched her and she watched us. One evening Jim was sitting on the steps watching her and she started walking straight toward him. She kept getting closer and closer and he was just ready to move when she turned around and looking him in the eye over her shoulder delivered a fresh pile of blueberry seeds. Then she walked away. We never did get any berries to grow. But the experience was priceless.

A scientist from the Connecticut agricultural experiment station whose name I don’t recall was known as the deer poop guy. He collected deer poop for a study on the role of deer in spreading invasive species. In the greenhouse, he grew a lot of different plants. I recall it containing a lot of pokeweed.

This is a good way to get an early start on reintroducing plants to a mountain top removal sites here in Central Appalachia…and we have many bears to follow around. They do a good job of leaving these piles behind. To be able to use them in our new high tunnel will be a good start on our reclaiming these sites.

Thank you for your research and your time to share these results.

This discussion enriched my day, thrilled my heart!

Look at seeds before planting and image a sample, then image the seedlings after the first true leaves have formed. Basic scatology. You will develop the ability to ID the plant from the sample.

Dang, I know where that bear has been and gone!☺️

Clever. Bears can be very useful if you know how to use them.