A river of birds, barely noticeable to people on the ground below, gracefully moves above forests of Douglas fir and lodgepole pine, floating through the Bitterroot Valley in southwest Montana.

Moving through the dark, hundreds of different species pass unknowingly over a small white bucket, perched on top of a wooden pole, with a solar panel resting at the bottom.

Inside the inconspicuous bucket is an acoustic microphone. Capturing chirps, tweets and buzzing noises, this microphone is part of a nocturnal flight call project being conducted by researchers at MPG Ranch in Florence, Montana.

Beyond the Telescope

Blending into a pitch-black sky, nocturnal migrations are almost impossible for researchers to track for purposes including population counts or species diversity rates. Knowing what species are stopping over is important for conservation. Essential habitat can be preserved for the right species and monitoring helps track changes across decades.

Most songbirds choose to migrate at night because there are fewer predators and skies are more likely to be less turbulent. Colder temperatures at night also help, as flying is a high-energy activity that generates large amounts of heat.

Into the early 2000’s using a telescope to count birds that flew across the moon was the most common method of nocturnal research. This method was incredibly imprecise and made it almost impossible to tell different species apart.

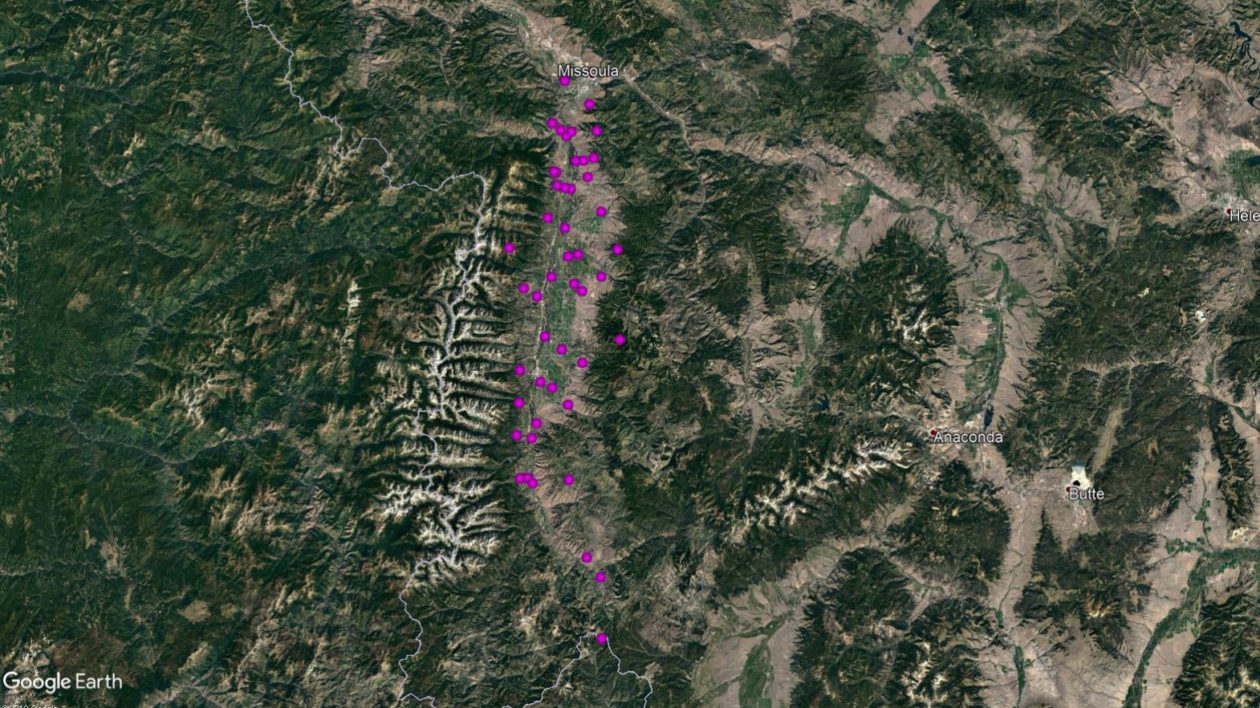

Avian scientists Debbie Leick and Kate Stone learned more about bioacoustics, a more efficient method than moon counting, at a North American Ornithological Conference in 2012. The researchers started with 3 recording units in 2012 and grew to over 50 microphones in 2019.

“I believe this is a record-breaking size acoustic recording study,” Leick said.

Collected data have shed light on the quantity of birds flying over Montana and have included unexpected species.

“We’ve certainly got our handful of totally surprise birds, different warblers or thrushes, shorebirds, that we didn’t know would be here at all,” Stone said.

Not knowing which birds are around impacts conservation efforts and makes it difficult to track changes over time.

The project uses devices called Autonomous Recording Units (ARU’s). Each unit consists of a microphone on top of a tall pole that can detect bird calls 600 meters up in the sky and a distance of 300 meters away from the microphone. The units are solar powered and also pick up calls from elk, coyotes, frogs and insects.

The units record continuously from an hour before sunset to an hour after sunrise during the migration season.

This project answers migration, species distribution and behavior questions using passive methods, Stone said.

“It reduces the risk to the birds and it also increases the power of our sample size,” Stone said.

Information Overload

A drawback of non-invasive data collecting is the sheer amount of information collected. The researchers use a software called Vesper to view and analyze the nocturnal flight calls.

In order to calibrate the software, the researchers used portable recording stations to gather reference calls. Similar to sound-proof recording studios for humans, the researchers placed birds in the booth and played them recordings of nocturnal flight calls from similar species.

Listening to the other calls elicited the birds to make vocalizations of their own that are used for classification and cataloguing.

Leick and Stone hope that eventually citizen scientists will be able to use the software to analyze their own recording calls, however, the technology is not yet at that point.

The researchers gathered a beta tester group in late 2020 to test the Vesper software. Their goal is to help find “bugs” and provide suggestions for future development.

“Particularly in these pandemic times we started to see more participation on some of the nocturnal flight call forums and other places,” Stone said. “People that are kinda going stir crazy on lockdown in a city.”

Stone also said the software is of interest to aging individuals that might have physical challenges but could use Vesper to experience birding.

“Although it requires some computer skill and being stationary, it also opens up a new world of birding,” Stone said.

Harold Mills is the Vesper software developer and programmer. After working for the Cornell Lab of Ornithology for 11 years, Mills created the program in 2012. The vision guiding his work is the possibility of thousands of monitoring stations around the continent listening every night recording millions of birds.

“We could provide that information to people on the internet in essentially real time. That’s the prize we are heading towards,” Mills said.

In Montana Leick and Stone are already expanding the number of recording stations. In addition to placing recording units on MPG ranch property, the researchers found local landowners in the Bitterroot Valley that were willing to host a unit on their property.

One of the recording units is located on Kit and Joe Tilly’s property, 20 miles south of Hamilton along the Bitterroot River.

Kit is a retired microbiologist who worked at Rocky Mountain Laboratory and Joe is a retired pilot.

“We are just wannabe wildlife biologists,” Kit said.

The pair were caretakers of their property for a number of years before purchasing it. Staying active through retirement, their goal is to eventually use the entire space as an area for research.

“It’s low effort for landowners to participate in research,” Kit said. “We get the added benefit of interacting with these people who are really quite amazing and know so much about birds.”

Join the Discussion