Small-scale fisheries are an under-recognized source of mortality for sea turtles. A new study from the Solomon Islands finds that free divers harvest more than 11,000 sea turtles each year, fishing local populations at unsustainable levels.

The Gist

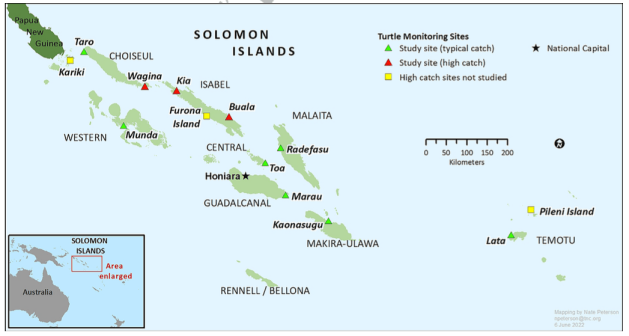

Nature Conservancy scientists trained and paid community monitors to collect data from Solomon Islands fishers on turtle catch, including photographs and geographic data on the reefs where they fish. They collected more than a year of data from 10 nationally representative sites across the country.

Monitors recorded data on 1,132 turtles that were caught and killed. Analyzing these data, researchers found that 73.3% of turtles harvested were endangered green turtles, and 25.7% were critically endangered hawksbill turtles. The vast majority (92.6%) of turtles were captured by free divers who use low-tech snorkeling and fishing gear to target a wide range of coral reef fauna. Most turtles were caught as everyday food for the fisher’s family, or as a special meal for cultural events like birthdays, funerals, weddings, and church festivals.

The researchers then built a mathematical model that provided a statistically robust estimate of national sea turtle harvest rates. They estimate that more than 11,000 turtles are harvested from the Solomon Islands each year. Interviews with experienced free divers suggest that the rate of turtle harvest has declined nearly 5-fold over the past 30 years, indicating that fishers are killing turtles at unsustainable levels.

The Big Picture

Sea turtles are harvested in small-scale fisheries across the world, and most of the efforts to quantify the number of turtles killed in these fisheries come from the Atlantic, Caribbean, Eastern Pacific, and the Mediterranean. Few attempts have been made to obtain similar data from the Pacific Islands, despite this region having the highest rates of legally harvested turtles in the world.

“Fishers don’t catch turtles often, but when you consider that there are 4,000 coastal communities in the Solomons Islands… it really adds up,” says Richard Hamilton, Senior Conservation and Science Advisor for the Nature Conservancy’s Asia Pacific Region and lead author on the paper. Subsistence take of all turtle species — except leatherbacks — is legal in the country, and turtles are typically fished opportunistically, along with other species like reef fish, crayfish and trochus.

This study is the first comprehensive assessment of sea turtle harvesting in a Pacific Island country, and its methodology could help quantify harvest rates elsewhere in the Pacific.

The Takeaway

Hamilton and his colleagues shared the results of this study with the national government and other stakeholders in 2019, and their recommendations were integrated into the Solomon Islands National Plan of Action for Marine Turtles 2023-2027. The document acts as a strategic national plan for turtle fisheries and conservation.

While policy and strategy are critical, Hamilton says that it’s insufficient in countries with limited enforcement capacity. Regulations prohibiting the trade in sea turtle products have been in place for decades in the Solomon Islands, and yet enforcement is so weak that visitors can easily find turtle products, like hawksbill turtle jewelry, in the international airport.

“There needs to be tighter enforcement of existing regulations that ban trade in endangered turtles,” says Hamilton. “And we also need greater support for nesting beach protection, because without that you’re dead in the water.”

The study found that 40% of turtles are being fished from just six communities, which have atypically high catch rates. “Getting those places under better management could go a long way towards protecting turtle populations, and it’s something that we’re discussing with the national government,” says Hamilton.

The biggest take-home, he says, is confirmation that small-scale fisheries may pose an enormous and under-recognized threat to sea turtles across the Pacific. “A lot of people, including scientists and policy makers, don’t think about turtles as a fishery,” says Hamilton. “But that’s how they’re treated in Pacific communities, and so the best way to manage them is by enforcing fisheries regulations.”