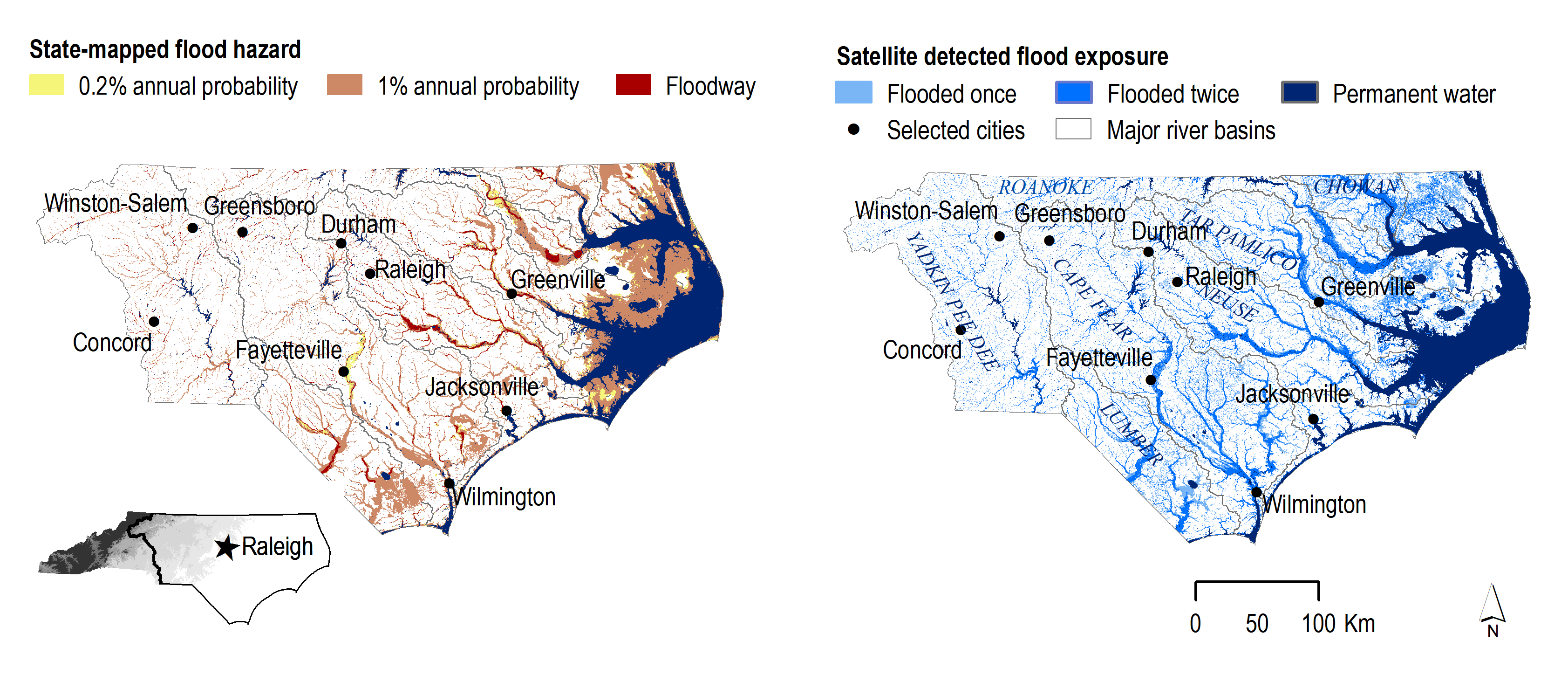

Using novel applications of satellite radar imagery and a specialized computer algorithm, a new study examining flooding caused by Hurricanes Matthew (2016) and Florence (2018) shows that current flood hazard maps are inadequate for accurately assessing flood risks and protecting communities in North Carolina.

The Gist

Published in Environmental Science & Technology, the paper by TNC NatureNet Science Fellow Danica Schaffer-Smith and colleagues at Arizona State University’s Center for Biodiversity Outcomes, finds widespread flooding from Florence and Matthew occurred well beyond the legal boundaries established by the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA) flood hazard maps and impacted a footprint more than 23 percent greater than the designated 100-year floodplain.

“The good news,” says Julie DeMeester, Director of TNC’s North Carolina Water Program and co-author of the study, “is that these findings can be used to identify changes in flooding risks under climate change and help communities be more resilient to future storms. From a wider perspective, the techniques and tools we developed are applicable for evaluating flood risks far beyond North Carolina.”

The Big Picture

Part of the problem in evaluating a flood’s real-time effects on water quality is that during or immediately after a storm, scientists can’t get good measures. During North Carolina’s hurricanes, notes Schaffer-Smith, “many sensors that measure water quality were offline due to flooding, and hazardous conditions didn’t allow for manual data collection, so government agencies had to rely on anecdotal reporting or delayed field sampling to assess the impact.”

It’s hard to know what contaminants are likely to be in the water if you don’t know what has been flooded and for how long. It’s a long-standing problem, and not just in North Carolina. To solve it, says Schaffer-Smith, “we used satellite-based radar to make up for some of these deficiencies because radar can penetrate through clouds and is highly sensitive to the presence of water on the ground, including beneath trees. That allows us to see the extent of flooding and assess true impacts.”

The paper also assesses the social-ecological vulnerability across floodplains and highlights opportunities to improve resilience. By overlaying the flood mapping with the Centers for Disease Control’s Social Vulnerability Index, which ranks census tracts to predict how well they will respond to disturbances like flooding, the researchers found that communities with senior citizens, people with disabilities, unemployed people, and people living in mobile homes were disproportionately affected by the storms.

The Takeaway

An accurate understanding of flood risk is foundational to making good decisions for protecting communities. The researchers identified areas where community buyouts of vulnerable homes and businesses may be warranted. It also gives conservation groups like TNC a blueprint for their work.

“We identified extensive areas where wetlands and forests could be protected and other places where these landscapes could be restored. Those nature-based solutions reduce flooding, filter pollutants from flood waters, and provide habitat for plants and animals,” says DeMeester. “That’s a cost-effective win for people and nature.”

Join the Discussion