New research published in Global Food Security shows that the paths to sustainable livestock production in systems around the world require a better understanding of environmental, economic, and social and cultural factors at scales small enough to be locally relevant, but broad enough to inform effective policy and funding interventions.

The Gist

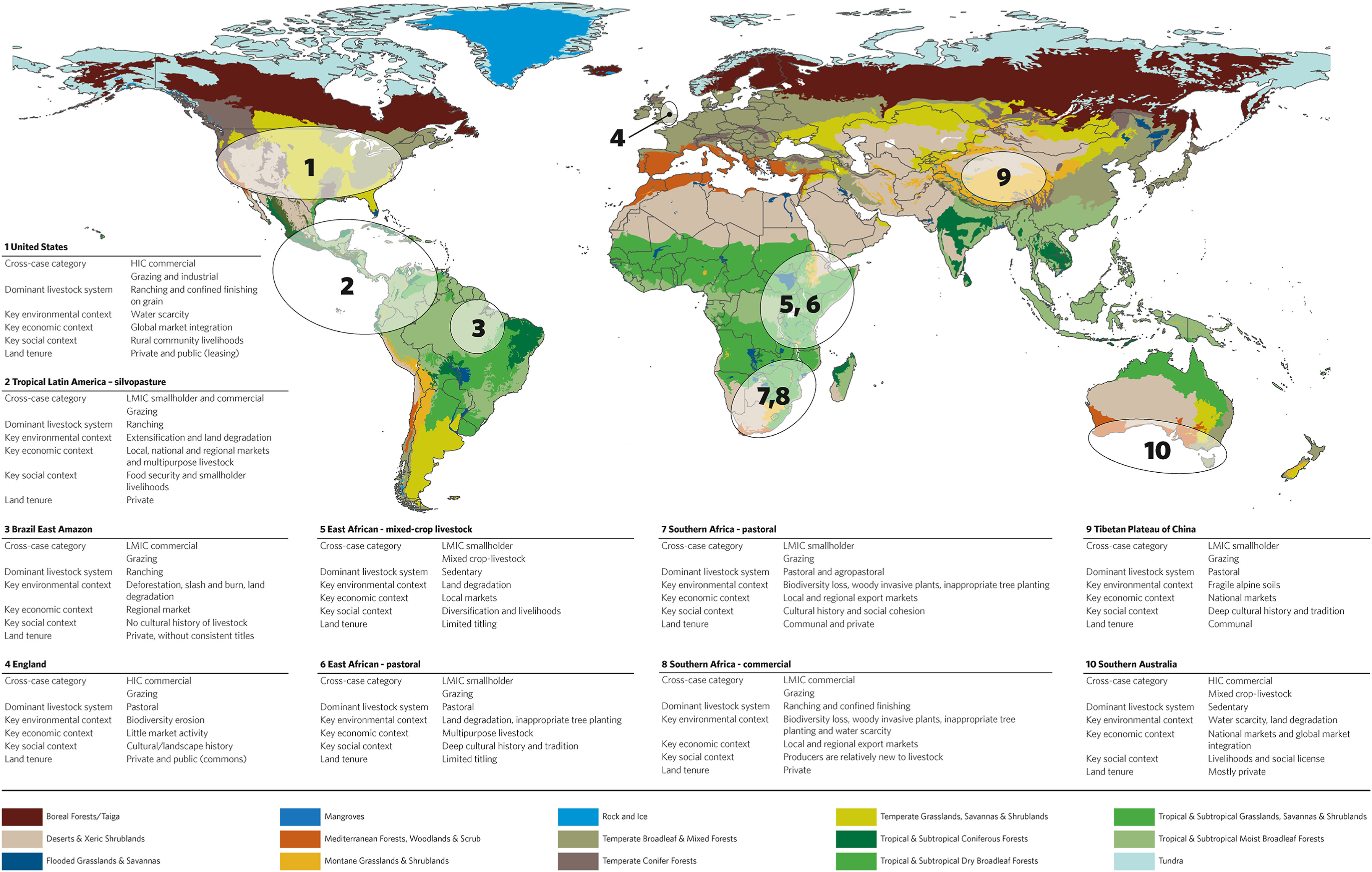

The paper, “Context Is Key to Understand and Improve Livestock Production Systems,” was written by a 20-member team of scientists representing 15 organizations and institutions from around the globe. It includes analyses of 10 expert-led case studies of ruminant livestock production systems from diverse agroecological regions, including from the Brazil East Amazon, East Africa, England, Southern Africa, Southern Australia, Tropical Latin America and the Tibetan Plateau of China.

The researchers found that a comprehensive understanding of place- and systems-specific environmental, economic, and social and cultural contextual factors, along with a comprehensive view of outcomes, is necessary to enact effective policies, secure investments and inform future research aimed at increasing the productivity and social benefits gained through livestock system sustainability.

The Big Picture

“More than three-fourths of the world’s agricultural lands are used for livestock production, and the farmers, ranchers and pastoralists that manage these lands use different systems and practices based on the unique circumstances of their geography,” said Clare Kazanski, lead author and senior scientist with The Nature Conservancy (TNC). “There is no one-size-fits all solution to achieving sustainability across these lands and production systems, but an understanding of the distinct, varied contexts of these locations can drive meaningful change for people and nature.”

Each of the systems included in the study have distinct barriers and enabling conditions for improving livestock production, but there are also emergent patterns the researchers identified that can point towards effective solutions by economic context and primary market setting. For example:

- In Tanzania’s Tarangire-Manyara ecosystem, technical advisor programs, attuned to the cultural contexts of the region and its people, could help herders adopt practices to improve livestock breeds for enhanced resilience and productivity and grazing strategies to reduce land degradation.

- In the Colombian Andes, livestock producers strive to adopt the practice of silvopasture—the integration of trees into grazing systems—to restore degraded landscapes, diversify farm profits and enhance biodiversity. Policies that provide financial incentives, along with training and technical assistance, can enhance the producers’ ability to adopt silvopasture, which will benefit both producers’ livelihoods and nature.

- In the Great Plains of the U.S., ranchers operate where local traditions intersect with global markets. Targeted incentives such as payments for ecosystem services could encourage ranchers to integrate these conservation practices, bolstering biodiversity while maintaining agricultural productivity.

The Takeaway

Combining production system type with overarching economic context emerged from the case study analysis as a useful starting way to categorize similarities and differences among individual cases. This was because local, regional, and global economic and market context, of all the contextual elements explored, is particularly fundamental to understanding existing systems and practices, as well as the enabling / constraining conditions and potential interventions for changing practices.

“Tradition has been for researchers to seek panacea innovations that apply to all production systems and agroecological regions” said co-author Matthew Harrison, professor and Systems Modelling Team leader, Tasmanian Institute of Agriculture, University of Tasmania. “Our study shows that such conceptualization is fundamentally flawed. For effective, inclusive and sustainable change, purported solutions must account for not just biophysical factors driving production, but also the economic, social and cultural factors that underpin the historical development of livestock systems in any given location. In that way, enablers and inhibitors of change are more likely to be accounted for, which is essential for any innovation to be adopted for the long term.”

The research project was funded by the MacDoch Foundation and led by TNC. Co-authors on the paper are from World Resources Institute; JG Research and Evaluation; Oxford Martin School, University of Oxford; University of Cape Town; Conservation South Africa; Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation; University of Queensland; Egerton University; Environmental Change Institute, University of Oxford; Cornell University; Wageningen University; AgNext, Colorado State University; Tasmanian Institute of Agriculture, University of Tasmania; and University of California, Berkeley.