I stepped quietly along the trail, scanning the branches. The relative openness of the lodgepole pine forest allowed for a lot of bird sightings, just not the bird I sought. I stopped and scanned with my pair of binoculars: red-shafted flicker, hairy woodpecker, black-capped chickadee.

I moved on and saw flitting movement amid a tangle of branches. A careful search revealed a red-breasted nuthatch. I watched it pluck insects from the bark for a few minutes.

This species is always a treat to see, but my day was devoted to finding a much rarer prize: the Cassia crossbill. This bird is found only in two small, isolated mountain chains in southern Idaho. Its entire range covers only about 27 square miles.

This crossbill has a fascinating evolutionary and ecological history. I came to explore its unique habitat and, hopefully, catch a sight of Idaho’s only endemic bird.

A Coevolutionary Arms Race

As a naturalist, I’m drawn to endemic species, animals and plants found only in a limited geographic area. Endemics are most often associated with islands, but they can be found in any isolated habitat. There are fish found only in an alkaline lake in the eastern Oregon high desert and snails restricted to small springs of cold water along Idaho’s Snake River.

When a fish or a snail population is cut off from the rest of its population by geological events (a lake drying, changing river levels), you can easily see why they might evolve in isolation. But birds? Most birds fly and many migrate long distances. With passerine birds, they are almost constantly coming and going.

Islands are known for their endemic birds. The Hawaiian islands were home to at least 70 endemic species (sadly, many are now extinct). By contrast, the entire 48 contiguous US states are home to only 16 endemic birds. And some of these species have quite large ranges.

So how does a finch become restricted to a small part of the interior state of Idaho? After all, the closely related red crossbill is found widely throughout northern and western North America.

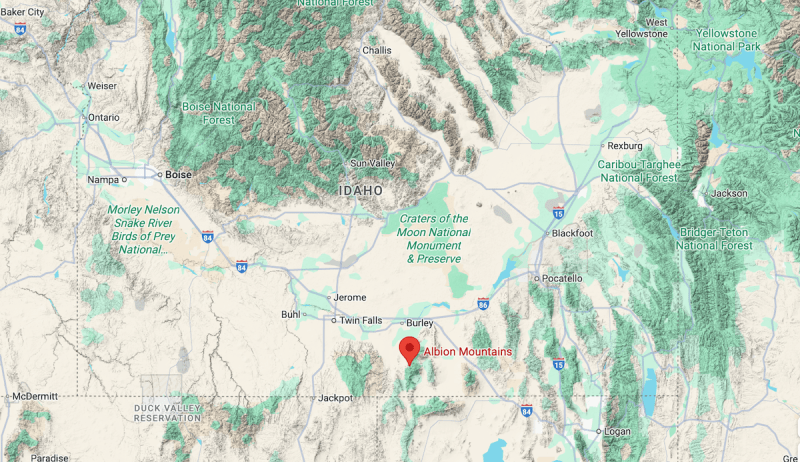

The South Hills and Albion Mountains, located in Idaho’s Cassia County, are isolated from the mountain ranges found to the north. They’re surrounded by sagebrush and high desert. These mountains were colonized by lodgepole pines, a common species in the western United States.

Due to the isolation of these ranges, the pine squirrel (also commonly called the American red squirrel), never populated the forests here. This absence has profound effects.

I spend a lot of time hiking, camping and cross-country skiing in Idaho’s conifer forests. The chattering of pine squirrels is a near-constant companion, so much so that it becomes one of those background noises you barely notice. Until it’s not there. Upon arrival to the South Hills on my crossbill quest, I soon had the thought of something missing. No chattering, no little squirrels skittering through the branches.

These squirrels, it turns out, also play a significant role in shaping conifer forests. They’re also the major competitor of the red crossbill. The crossbill is constantly on the move, what ornithologists call a nomadic species.

In the South Hills and Albion Mountains, lodgepole pines evolved without the influence of squirrels. Pine cones grew in great abundance. Red crossbills found a plentiful food source, without the usual competition. A nomadic bird became sedentary.

The crossbills evolved thicker beaks to specialize on lodgepole pines, whose cones red crossbills can’t open. Like other crossbills, the Cassia crossbill’s bill looks almost like a scythe. This in turn led to the lodgepole pines evolving thicker cones. It led to, as researcher Craig W. Benkman noted in the journal American Naturalist, “a coevolutionary arms race.”

Benkman studies crossbills and is the one to first document these changes. The red crossbill species exhibits 10 “call types,” each one specializing in a different species of conifer. But due to changing cone abundance, these crossbills move around considerably. The Cassia crossbill is the first one to be named a separate species, recognized officially as such in 2017.

It can be difficult to reliably see a red crossbill as they are constantly on the move. But the Cassia crossbill stays in the same isolated forests all year round. The few trip reports devoted to finding them listed several reliable locations. I set off with high hopes, but years of birding experience taught me to not count my crossbill before it was in front of me.

Woodpeckers and Quaking Aspens

On a sunny September day, I headed into the South Hills eager for a crossbill encounter. As is often the case, I was fitting the outing between work and family obligations, so had somewhat limited time.

Much of the drive was through the cheatgrass-infested plains, agricultural lands and sagebrush country that dominate southern Idaho. Then I began climbing up a road leading to the South Hills, as stands of aspen and the occasional pine began to appear.

I chose a campground as my first stop, as it was the first substantial stand of lodgepoles I found. I pulled in and immediately saw a bird flit across the parking lot. Could it be this easy? Of course not.

A quick look through the binoculars revealed a hairy woodpecker, then another. In the next ten minutes, I’d see four more. This woodpecker abundance is not unusual in the South Hills. Pine squirrels are also nest predators. In their absence, many birds – including the woodpecker – live in higher-than-usual numbers.

The same is true of crossbills. They exist at densities 20 times higher than red crossbills, a fact that again fueled my hopes as I hiked down the trail.

The birds were out, ranging from abundant species I see daily (American robin, red-tailed hawk, black-billed magpie) to the more notable (mountain chickadee, red-breasted nuthatch). But no crossbill.

I walked on, enjoying a glorious September day at high elevation, stopping to watch the aspens quake in the breeze and observe a pair of Uinta chipmunks – an unusual mammal sighting – as they foraged in the branches.

But where were the crossbills?

An Uncertain Future

Undoubtedly, it would have been much easier to find a Cassia crossbill ten years ago. The species has declined significantly in recent years.

For wildlife with large home ranges, local threats seldom mean extinction. If there is a fire or flood, the animal can just move. Endemic species with limited home ranges are much less resilient in the face of threats. This can clearly be seen with islands, where an invasive predator can quickly wipe out bird species. In fact, more than 90 percent of the birds that have gone extinct in modern times have been island endemic species.

The Cassia crossbill lives on a different kind of island but it is still isolated and reliant on a limited food source. This makes it vulnerable to change. In 2020, a wildfire raged through the Albion Mountains, eliminating a lot of lodgepole pines. Researchers estimated the Cassia crossbill population was cut in half by this one event.

Researcher Craig Benkman has warned of the species’ “impending extinction” due to fire and climate change. Lodgepole pines have difficulty thriving in a warming climate and become more susceptible to pests like mountain pine beetles. The one slight bit of good news here is that the abundant woodpeckers of these mountains have made beetle infestations less severe than in other parts of the West.

After the 2020 fire, there were reliable Cassia crossbill sightings in Colorado, Wyoming and California. Did the birds set out in search of new habitat? Could the birds thrive elsewhere? Perhaps, but it’s probably not enough to save the species. Their future rests with these islands of lodgepoles, with still-abundant food and no squirrels.

The Search Continues

Even a few square miles of pine trees start to feel daunting when you’re not finding birds. There are a lot of trees to check.

Creature quests can take on a strange energy. Find the bird or mammal you’re seeking immediately, and you’re flooded with a dose of relief tempered by a bit of disappointment. You came here for a search and you don’t want it to be over too soon. But when you haven’t found the critter after extended searching, the thrill of the chase starts to be tinged with anxiety.

I had to drive a couple hours back home for my son’s football practice. I’d been looking for a few hours and had no luck. I moved locations to another patch of lodgepole pines.

Bits of cone littered the trail. The work of crossbills? Hope increased. I slowed down, still tracing every flitter of wing I saw. A mule deer snorted. An aggressive wasp buzzed my face. A small yellow bird – a warbler? – offered a brief glance.

I sat on a stump in a patch of lodgepoles with a lot of bird activity. And then I heard the tell-tale “kip” made by the crossbill, a sound I had committed to memory. I stood up, binoculars at the ready. My heart lurched when a flock of birds flushed, but it was just juncos.

And then. Two birds landed on a lodgepole pine branch, silhouetted with blue sky. I looked and saw the unmistakable “crossed bill.” A male and a female sat there, shifting positions but offering crystal-clear views. I stared until, a few minutes later, they departed.

I continued to look but didn’t see any more. But I felt that glow that any birder or wildlife watcher knows after seeing a target species.

I love everything about wildlife quests like this. I love how being alert allows you see more, so much more: from a deer trotting in the shadows to individual trembling leaves. I love sneaking through the woods, driving dusty roads and celebrating with gas-station burritos. I love the way that news cycles and work assignments fade from your mind.

And I love how searching for an endemic bird fully immerses you in the complexity of the world. What might look like just another set of hills from the highway is revealed to be a habitat shaped by a lack of squirrels and abundant woodpeckers and thick pinecones. And that place offers you a glimpse of this special bird, one that exists only here, as if clinging to a lodgepole life raft in the desert.

Congratulations on the lifer. I grew up in Twin Falls and often wonder if I saw them in the South Hills where I spent a lot of times from my earliest camping memories, miles of hiking hunting and many hours cross country skiing. I noticed birds other than those I was hunting for food but was not a birder so spent no time identifying non game birds.

Now that I am a birder I have not made the trek back home to try and find them, I guess I should get down there while they are still around and give it a go.

Love this! Especially those last two paragraphs <3

Thanks for sharing this experience.