With clumsy steps, the bear cubs follow their mother through the valley of blooming frailejones, which seem to touch the clouds. The mother bear carefully searches the ground for juicy bromeliads of the Puya or Cardón species, one of the favorite delicacies of the Andean bears that inhabit the Latin American páramo.

The Andean bear is recognized by its dark brown to black fur and the whitish markings on its snout, neck chest, and sometimes around the eyes (which is where it got the name “spectacled bear.”) The name is misleading, though, because those spectacle markings are really only present in a small number of individuals.

Using the strength of her claws and teeth, mother bear tears away the firm, triangular leaves, covered in tiny spines, to reach the heart and the most tender, flavorful, and nutritious parts of the plant. From a distance, it looks as though she were peeling a giant artichoke.

Stories of TNC in Latin America

Andean bears are primarily herbivorous, feeding on bromeliads, palm buds, and oak fruits, though they will also consume carrion and occasionally livestock, as they are omnivores.

While the mother works, the cubs play among themselves—nibbling each other’s ears, pushing with their paws, and rubbing against the cushiony moss. They will remain under their mother’s care until they are about a year and a half old. After that, they will begin to roam for long distances on their own, like adult bears do, climbing trees to feast on fruit, building shelters, and even swimming creeks, rivers and lagoons to cross the high-altitude landscapes of the Andes.

Despite their bulk, Andean bears are remarkably agile. However, they won’t reach sexual maturity until they are four or five years old, according to current data from bears in captivity.

Encounters with this particular bear family have become increasingly common. They live in Chingaza National Natural Park, a protected area situated at 3,000 meters above sea level and just 30 kilometers from Bogotá—one of Latin America’s largest metropolises. Much of this is due to the cubs’ curiosity, as they give free rein to their exploratory spirit and are drawn to unfamiliar scents, making the mother bear’s job of keeping them safe a constant challenge.

They are not the only bears spotted in the area. With a bit of luck—and if the mist lifts to reveal the páramo in all its splendor—one might glimpse more of these bears, known as the wanderers of the Andes.

A Mysterious Guardian of the Highlands

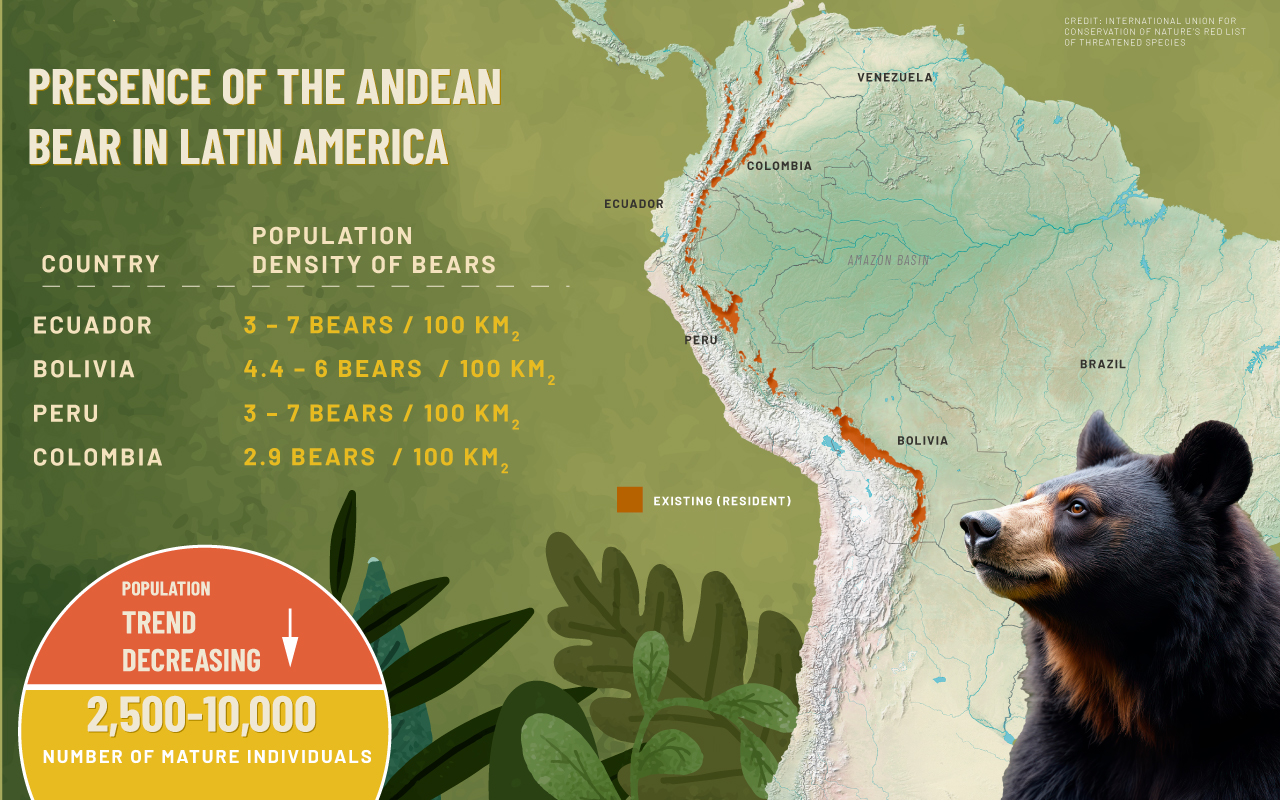

Andean bears are the only bear species found in South America. They range from northern Colombia to Argentina, constantly moving through the various forest ecosystems found at different altitudes in the mountains in search of food. In the Páramo the vegetation is mostly low-lying and covered in fine hairs that absorb moisture from the air, channeling it into the soil and giving life to streams and rivers.

“Seeing them is something very symbolic,” says nature photographer Sebastián Di Doménico, who has spent the past seven years photographing them in the páramos of Ecuador and Colombia. “They are large and very shy. They’re relatively easy to spot from a distance because of their black fur, but the quality of the encounter depends a lot on chance. Being close to them is very, very rare, but when it happens, it’s a unique experience.”

With their flat faces, powerful jaws, refined sense of smell, varied diet, and strong appetite for plants, Andean bears are natural seed dispersers, playing a vital role in the ecosystems they inhabit. They are also known as the “gardeners of the forest” because they love to climb to the treetops to feed on fruit.

In doing so, they break branches and alter the structure of the trees, creating openings that allow sunlight to reach the forest floor—giving seedlings the chance to grow and renew the forest. Their presence is a sign of a healthy ecosystem, which is why they are considered an “umbrella species.” Protecting them means protecting countless other species that share their habitat.

Despite being one of Latin America’s most iconic species, much about the Andean bear remains a mystery. There is still a lack of standardized scientific data to determine conclusively whether their populations are increasing or declining in the wild. This highlights the importance of ongoing research efforts, such as those led by the Alexander von Humboldt Biological Resources Research Institute and the Wii Foundation in Colombia.

Nicolás Reyes, one of the authors of a recent study and a member of the Andean Bear Specialist Group of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), as well as curator of the mammal collection at the Humboldt Institute, explains that thanks to telemetry collars fitted on some individuals in Chingaza, researchers have begun to gather valuable insights.

One of the most striking findings is that these bears are great wanderers, traveling an average of 15 kilometers per day through rugged mountain and forest terrain—often ignoring the boundaries of human-defined landscapes.

“Andean bears are animals that require vast territories in a world where natural space is shrinking, increasingly transformed by agriculture, livestock, and urban expansion. As a result, encounters between bears and humans are becoming more frequent, because we are encroaching on their home,” explains Reyes. “This presents a major challenge: to rethink conservation on a landscape scale and ask ourselves how we can use resources more sustainably. Saving them, in many ways, is about saving ourselves.”

Habitat Loss and Fragmentation Are Challenges

In addition to habitat loss, Andean bears face other serious threats such as hunting and the severe fragmentation of their environment. Although their range spans the entire Andes mountain chain, they are now found primarily in small, disconnected patches. This isolation affects their genetic diversity, forcing them to reproduce within the same family groups and making them more vulnerable to disease and early death.

The Nature Conservancy works to protect the habitat of the Andean bear safeguarding watersheds and preserving the biodiversity of these unique páramo ecosystems. Some of TNC initiatives include the creation of water funds — more than 26 operate across South America — where users contribute financially to conservation activities that protect water sources, ecosystem restoration, working with communities on education about the importance to preserve this ecosystem and studies to estimate the potential for paramo ecosystems to help mitigate climate change.

Exclusive to Latin America, páramos are high-altitude ecosystems found between 2,900 and 4,000 meters above sea level in the Andes of Ecuador, Colombia, Peru, and Venezuela. These unique landscapes are vital for regulating the water cycle, acting as natural “water factories” by capturing, storing, and gradually releasing water to lower elevations—sustaining rivers, agriculture, and cities alike.

By investing in the health of the páramo, these programs ensure the long-term availability of clean water while preserving the habitat of species like the Andean bear.

As night falls over the Chingaza páramo, the mother bear and her cubs seek shelter beneath rocky outcrops. Under the moonlight, the frailejones take on the shape of guardians—protectors of a unique territory once considered sacred by the Muisca people, the Indigenous inhabitants of these highlands.

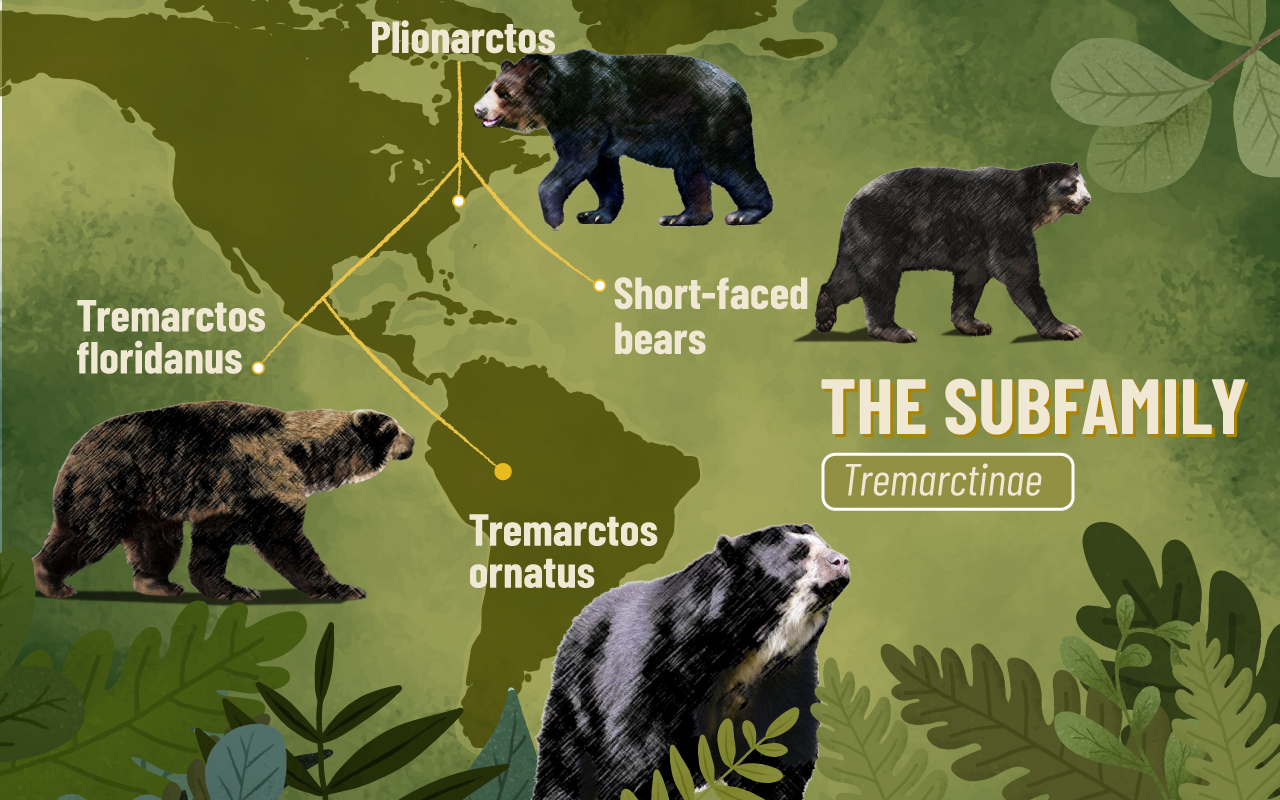

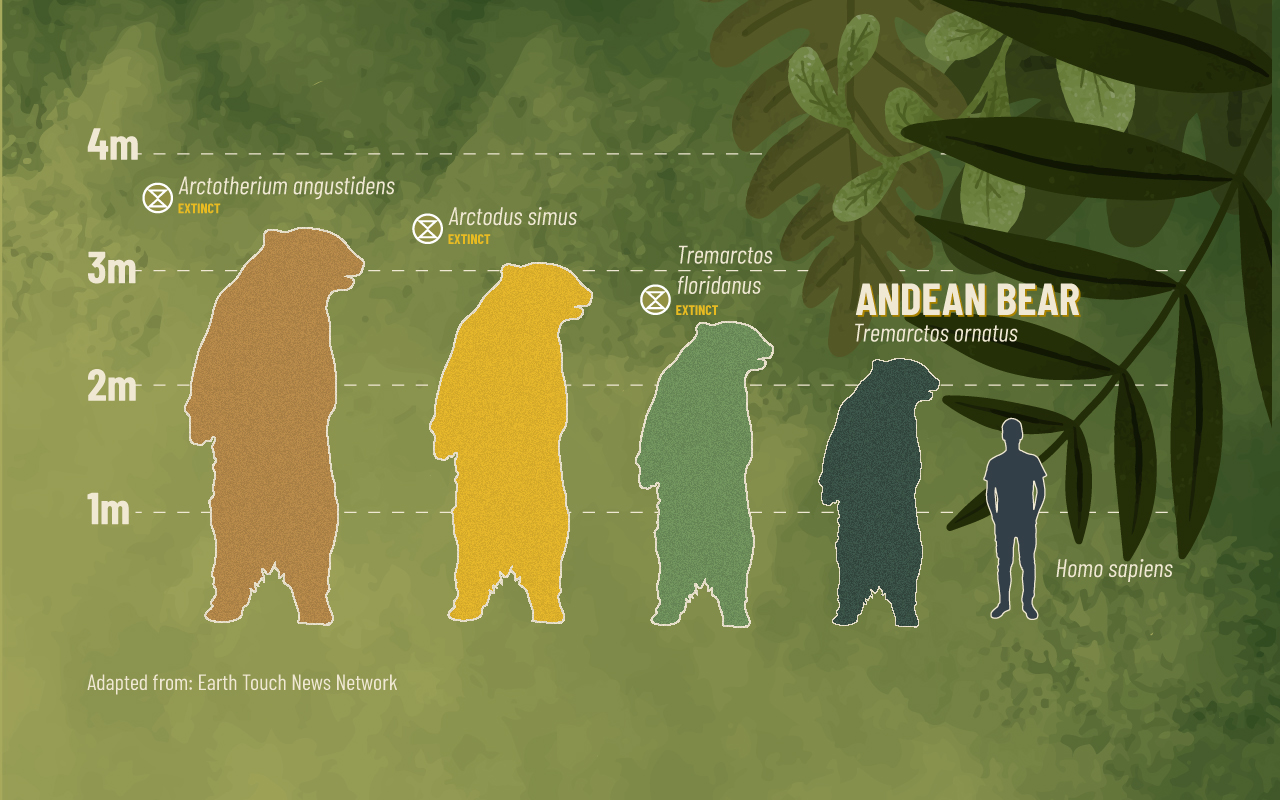

Here, where the fundamental elements of life and cosmic balance converge, the last wild descendants of the short-faced bear lineage of the Tremarctinae subfamily still roam—the Andean bears, those great wanderers of the Andes.

Join the Discussion