It’s difficult to imagine an invasive species that’s generated more media attention (and hysteria) than the northern snakehead.

Since it was first documented in Maryland in 2002, it’s generated headlines proclaiming it the “Frankenfish” with dire warnings of its spread. And it has spread around the Chesapeake Bay watershed as well as to other waters along the East Coast and even in the Mississippi Basin.

Objectively, the northern snakehead has been a conservation problem, but is it a problem on the level of, say, the zebra mussel or the emerald ash borer? Probably not.

The arguably more invasive brown trout is beloved and is featured in movies starring Brad Pitt. The snakehead, on the other hand, is portrayed as a terrifying creature that is the villain of several B-grade horror movies.

Studying the real snakehead goes beyond this hype but is perhaps no less strange. One of this fish’s most reported habits is its ability to move about on land. How does such a large fish accomplish this?

The answer, according to new research, may lie at least in part with another of the snakehead’s infamous features: its slime.

The Snakehead Collector

Noah Bressman has a love for all things fish: he studies them, he communicates about them, he catches them. His arms are covered in fish tattoos. I’ve had the pleasure of fishing with him a couple of times, and he’s laser-focused on catching new species.

As assistant professor of physiology at Salisbury University, his academic focus is on amphibious fish, those species that can also move about on land.

“Snakeheads are a lot bigger than most amphibious fishes, like the walking catfish,” says Bressman. “I wondered how slime assisted the snakehead in moving on land.”

That’s difficult to measure, especially as research needs to have consistency. Instead of trying to find sensitive, sophisticated (and expensive) equipment, Bressman decided to go low-tech.

“What if we pulled snakeheads over the ground and compared it to other fishes?” Bressman asked.

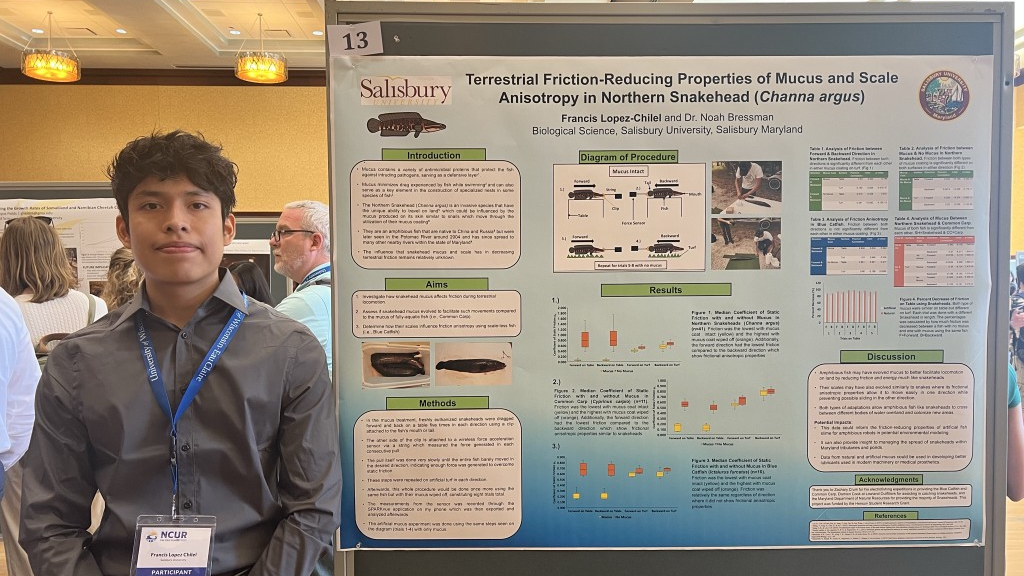

One of his students, Francis Lopez, thought it would make for an interesting, and unique, undergraduate research project. “I wanted to challenge myself,” says Lopez. “This was out of my comfort zone.”

First, he had to acquire snakeheads. The fish would be caught and humanely euthanized; as an invasive species, the fish can be removed without conservation concern. One issue: Lopez had never fished before.

Snakehead fishing is notably difficult, even for experienced anglers. I’ve tried several times and have failed; the snakehead remains one of my “most wanted” species. Lopez enlisted the help of local guide Damien Cook, well known for catching the world-record northern snakehead.

“Snakehead fishing was a lot harder than I thought,” says Lopez. “The first time I hooked one, it was a real shock. But it’s cool that my research project was not only really interesting, it also led me to a new hobby.”

Bressman also helped in the search for snakeheads, attending snakehead fishing tournaments to try to secure specimens. But first he had to establish his “field cred.”

“The first tournament I attended, I was given one snakehead,” says Bressman. “Snakehead anglers, as you might expect, love catching snakeheads. They fear researchers could negatively affect their fishing with the results of their research.”

The next tournament, Bressman entered as a participant. And he won. “It was only my third or fourth time fishing for them,” he says. “That really helped earn the trust of other anglers. It opened the door for me, and they started giving me fish.”

They also received fish from electrofishing conducted with the Maryland Department of Natural Resources. Two other invasive fish species – blue catfish and carp – were also collected for comparison purposes.

The Science of Dragging Fishes

The first thing Lopez noticed when he started catching snakeheads was just how slimy they were. “By the time this project was over, I went through a few shirts and a lot of paper towels,” he says.

The snakeheads had to be kept fresh to preserve this mucus layer. The research then involved measuring the friction required to drag the snakeheads, blue catfish and carp over two surfaces: a smooth plastic table and a rough artificial turf.

The experiment involved dragging the fish over both surfaces, once with their mucus intact and once with the mucus wiped off with a paper towel. They also dragged snakeheads re-coated with an artificial lubricant with similar properties to fish mucus.

The results were recently published in the scientific journal Integrative and Comparative Biology.

In summary, snakehead slime greatly reduced friction. As the paper notes, “The paper found that “by evolving mucus that reduces friction more compared to fully aquatic species like carp, [snakeheads] may be able to greatly reduce the energy cost required for terrestrial locomotion.”

The research concluded that snakehead slime was more effective in reducing friction on the smooth surface than the rough turf. Less friction on a smooth surface may not enable the snakehead to get enough traction to move around; Bressman likens this to trying to walk barefoot on an oiled-up linoleum floor.

The mucus also protects the snakehead from desiccation, important for a fish literally out of water.

But that also means that the longer the snakehead is on land, the slower it goes. “It’s not the same ease for them to move over land as time progresses,” says Bressman. “As the mucus dries, movement becomes more difficult.”

That is different from other amphibious fishes. Walking catfish, for instance, make use of rigid fins that allow it to shuffle about on land.

Still, the snakehead’s infamous slime – so often noted by anglers – likely plays an important role in the snakehead’s ability to move.

Implications for Conservation

As the paper states, “Amphibious fishes like snakeheads may have evolved particularly slippery mucus to aid in terrestrial locomotion by reducing friction and energy required to move overland, potentially facilitating overland movement between bodies of water.”

How far can they move between water bodies?

I pose that question to Bressman and, in short, it depends. In wetter conditions, like during floods, snakeheads would clearly have an easier time moving across land. During dry conditions, the snakehead’s mucus would likely help prevent it from desiccating as quickly as other fishes, but it would still face challenges.

“In dry conditions, snakeheads are unlikely to disperse as far as we originally thought,” Bressman says.

He also notes another potential application for the research: amphibious robots are increasingly used in a number of scenarios, including conservation monitoring. A lubricant that mimics snakehead slime could help such robots more easily transition from water to land.

Like many who get acquainted with snakeheads, both Bressman and Lopez study the snakehead in part to understand its spread and potential impacts. But they also recognize that this is a particularly fascinating animal. And for Lopez, they may have even altered his career path.

Originally a pre-med student, he’s had a change of plans.

“After I graduated, I was having an existential moment,” he says. “I realized that I really enjoyed working with animals. So I decided to go the pre-veterinary route instead of pre-med. Really, I just so enjoyed studying these snakeheads. I’m passionate about everything to do with this project.”

Snake heads should be eliminated they

are an nvasive species.

Fascinating research about this fish. And glad to know it turned a pre-med into a pre-vet.