On one of photographer David Walter Banks’ first trips to photograph Georgia’s Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge, he awoke in the middle of the night to a bellowing outside his tent. Convinced it was an alligator sitting just on the other side of the tent flap, he did the only thing he could think to do in the moment: He bellowed back.

“I just yelled at the top of my lungs,” he says. “And I don’t know whether it was a call in response to me or just because he was doing his mating call thing, but the gator bellows back. We go back and forth until I basically lost my voice.”

At sunrise, he unzipped his tent, and the gator was still there, but not on the elevated platform his tent was pitched on. It was in the swamp water—a relief to Banks who went on about his day.

“I’m certainly much more comfortable being in the swamp and around gators now,” he says. “That was one of the early trips.”

Banks estimates he’s spent at least 30 nights in the refuge, a stretch of blackwater swamp roughly double the size of New York City. Photographing its nooks and crannies—and raising awareness about a mine proposed just outside its borders—has become something of a passion project for him.

More from TNC Magazine

A version of this story ran in Nature Conservancy magazine. Join one of our editors as he takes his teenage son for a weekend in the Okefenokee.

“I just felt this extreme, almost spiritual connection to the place,” he says of his first trip there in recent years. “I came home and started researching more. I came to understand to a greater extent the importance of the Okefenokee ecologically and the threat that it was under. And it just felt like my project.”

The Okefenokee is largely undeveloped compared to other great swamps in the United States like the Everglades or the Great Dismal Swamp. It’s an example, its refuge director has said, of a functioning swamp. It’s full of carnivorous plants, more than 230 bird species, floating peat islands and, yes, alligators. It serves as the headwaters for two important river systems: the St. Marys River that flows to the Atlantic Ocean, and the Suwannee River that flows to the Gulf of Mexico.

Conservationists, including those at The Nature Conservancy, have raised concerns about the potential impact of a nearby proposed titanium dioxide mine on the hydrology of the swamp. The U.S. Department of Fish and Wildlife recently asserted its federal reserved water rights, which allows the government to sue should water be diverted from the refuge in a way that substantially harms its function.

Banks set out to photograph the swamp in a long-term project he calls Trembling Earth—a reference to the Indigenous name of the landscape. But celebrating a swamp, a type of landscape that’s not always beloved for its comforts, would be challenge.

“Sometimes you’re sitting there in the heat of the day, and everything just looks brown and bright and it doesn’t feel that magical but it still is: You might look around and be like, alright, everything’s dead. I don’t see any life. But, just beneath the water, right along the edge, there’s a million things that are about to bloom and grow,” he says. “I couldn’t do justice to the way this place felt by taking straight-forward documentary photographs.”

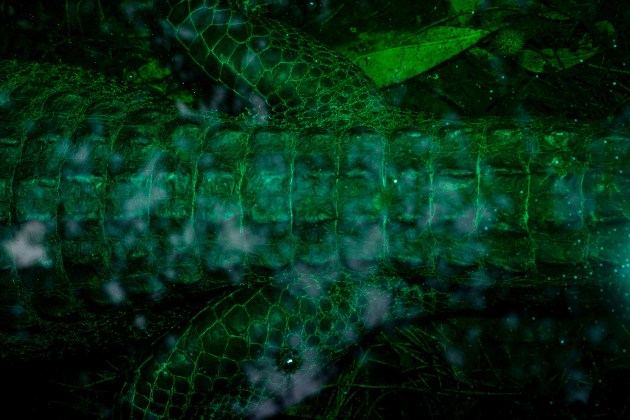

So Banks experimented. His photographs of the Okefenokee are vivid: pink Spanish moss draped over the trees, flashes of light, motion blurs, sparkling colors, double exposures. But there is no Photoshop trickery here.

“What you’re looking at in any photograph from this project is 100% created in camera,” he says. “I’m trying to evoke these feelings that I get while in this place,” he says. “But I also want there to be a level of truth that’s a baseline of the photograph: What you’re seeing is still a real thing that was there in real life.”

He used colored filters placed over flash units to project vivid colors onto the scene. He used double exposures and long multi-minute exposures that give a sense of movement and life to the swamp.

“Swamps have gotten bad PR over the years,” he says. “They’re sold as these things that are diseased or smelly but in fact they’re these kind of amazing biologically diverse cradles of life. … My photographs are meant to celebrate this place.”

Thank you for appreciating and teaching others to appreciate this primordial place through your beautiful photography.