On a warm, humid December night, a female leatherback hauls herself from the waves. She labors up the beach, one heave at a time, to lay her eggs within the dark, volcanic sands of the Solomon Islands. After just a few hours on shore, she’ll slip back beneath the ocean’s surface and begin a journey that will last thousands of kilometers.

Now, Nature Conservancy scientists and community rangers have discovered where this turtle, and others like her, migrate after they leave their nesting beaches. Data from satellite tags reveals the turtles’ epic journey from the tropical seas of the Solomon Islands to the cold, nutrient-rich waters of New Zealand and California. The tags also reveal just how vulnerable these endangered turtles are as they run a gauntlet of fishing gear and other threats across the vast ocean.

Tagging Turtles By Moonlight

Leatherback populations are declining across the world’s oceans, but the turtles in the Western Pacific are faring far worse than others. This genetically distinct subpopulation is critically endangered, having declined 83 percent in just three generations. Only 1,400 breeding adults are estimated to remain. If the rate of decline holds steady, as few as 100 nesting pairs could survive by 2040.

Nature Conservancy (TNC) scientists are working with conservation rangers in the Solomon Island’s Isabel Province to monitor the handful of key nesting beaches where these turtles haul out to lay the next generation. In November 2022, I joined the men and women conservation rangers for two weeks of fieldwork on Haevo beach. We patrolled the shoreline by moonlight, recording data on nesting turtles and collecting eggs to bury in protected hatcheries. That trip marked the beginning of a satellite-tagging program that would run at both Haevo and another nearby nesting beach, Sasakolo, for two years.

Scientists from TNC and the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) helped the rangers attach 17 satellite tags to nesting turtles, which tracked their migration route back to their cold-water foraging grounds.

Kia Ora, Leatherbacks

Leatherback nesting in the Solomon Islands peaks in the austral summer, with most turtles nesting from November to January. A small number of turtles nest in the austral winter, from May to July. “We aimed to tag turtles from both nesting periods, to see if the different nesting cohorts had a different migratory route or destination,” explains scientist Pete Waldie, director for TNC’s Solomon Islands program and lead on the research.

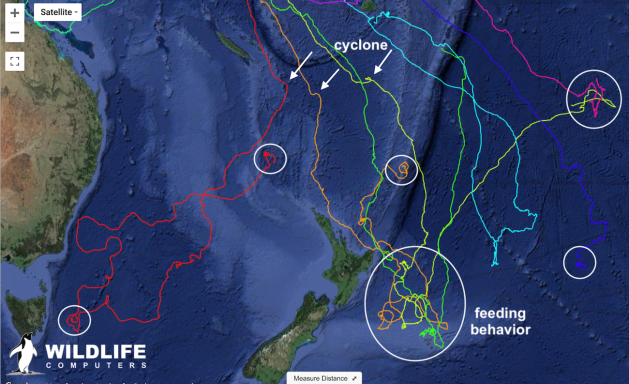

From November 2022 to January 2023, the Haevo rangers tagged 10 leatherbacks, including one during my time there. After laying as many as 5 or 6 clutches of eggs in the dark volcanic sands, the mother turtles swam southeast, to the cold waters off eastern New Zealand. They covered ground quickly, with some individuals swimming 60 kilometers (37 miles) per day.

One wayward female, Jijo, bucked the trend and headed west, swimming to Australia’s Whitsunday Coast. After working her way up the Great Barrier Reef, munching jellyfish as she went, she turned east towards Papua New Guinea.

Data from the tags provide clues to the challenges the turtles faced along the way. Several were temporarily blown off course when Cyclone Gabrielle swept across their route, the storm’s path visible as their colorful track lines diverted south before the turtles re-adjusted their direction. Other tracks revealed turtles stopping for several days to feed, their movement shifting from straight lines to looping swirls as they swam amid schools of jellyfish. Another turtle, Uke Sasakolo, dove to 1,344 meters (4,409 feet) below the ocean’s surface. This depth — equivalent to those reached by US Navy submarines — is the deepest dive ever recorded by a marine reptile.

The next austral summer, rangers tagged six more turtles at Sasakolo, another nesting beach on Isabel’s southern coast. Those turtles followed a remarkably similar route, heading southwest to New Zealand.

California Dreaming

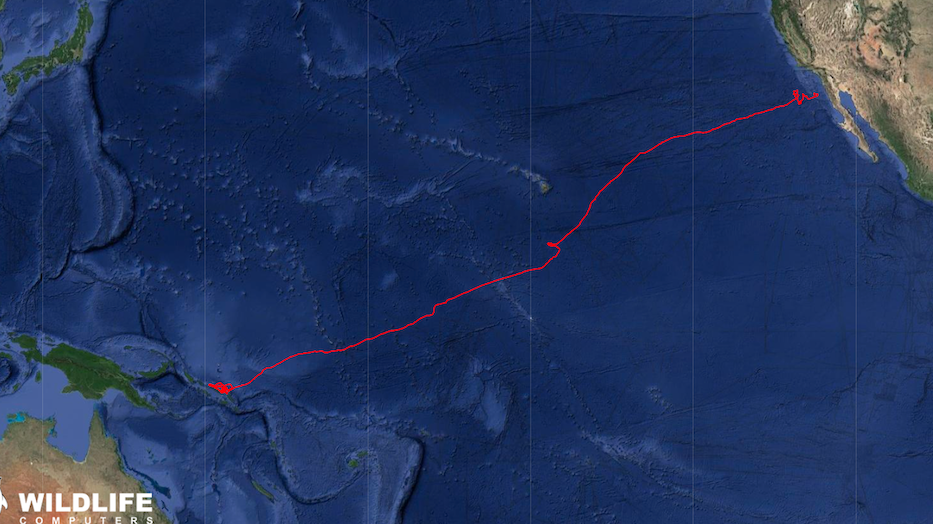

In May of 2022, Waldie returned to Haevo to try and tag turtles from the small cohort of mid-year nesters. The rangers found and tagged just one turtle, nicknamed Aunty June, who soon departed the Solomons to begin her migration. But instead of heading to New Zealand, Aunty June paddled her way, day by day, across the entire Pacific Ocean.

She swam northeast for six straight months, stopping to feed for several weeks just south of the Hawaiian Islands before continuing her migration. She reached the waters off Baja, Mexico on February 8th, 2023, a journey of approximately 10,000 km (6,000 miles) from her nesting beach. Waldie says that her tag is the longest functioning of any of the turtles in the study, transmitting data on Aunty June’s location for nearly a year before going dark as she foraged 185 miles south of Los Angeles.

Aunty June’s migration route wasn’t a complete surprise. A previous satellite tagging study by Scott Benson, who leads leatherback research in California for NOAA, recorded a single turtle making that same journey in the opposite direction. Tagged in the waters off California in the mid 2000s, the turtle swam to Haevo beach to lay her eggs.

In a twist of fate, that turtle was found on the beach by another Benson — Benson Clifford — now a conservation ranger at Haevo. Curious about the tag, he clipped it off the turtle and brought it to fisheries authorities in Honiara, the capital of the Solomon Islands, who then contacted Scott Benson in the US.

“That was the first time in my life I saw a live leatherback turtle, I was a bit scared and wondered if it would chase me if I approached it,” says Clifford. “When I learned the satellite-tagged turtle I found had come from the US, I was really surprised that it had come from such a faraway place.”

That serendipitous event put Haevo on the map as a critical leatherback nesting beach. When TNC decided to start conservation work at the site several years later, Clifford was one of the first to sign up as a ranger. More than a decade later, he remains one of the program’s most dedicated and knowledgeable leaders.

Linking Nesting Beaches & Foraging Grounds

Understanding the migration routes these turtles take — and their eventual destinations — is critical to their survival. “We suspected some of these turtles headed south, but it was surprising to see such a huge majority of them migrate to New Zealand,” says Waldie. “The tagging data shows us that the nesting protection in Solomons and bycatch prevention in southern Australia and New Zealand have to work hand in hand.”

Tracking Migrations

Eight innovative ways scientists are mapping migrations to make smarter conservation decisions.

It’s a sentiment echoed by Alexander Gaos, a marine biologist at NOAA and one of the collaborators on TNC’s tagging study. “You can have protected beaches or regulated fisheries, but if these turtles are killed in other areas that lack effective management, then it negates all the hard-fought conservation work,” he says. “We need to ensure that the different stakeholders and countries are working together and implementing real conservation measures.”

For their part, NOAA is using data from the tagging study to understand how leatherbacks use the waters around Hawaii and the Pacific coast of the US, then apply that knowledge to help regulate and minimize fishery threats. This includes shutting down the entire long-line fishery based out of Hawaii if it interacts with more than just a handful of leatherbacks in a year.

The satellite data from TNC’s study revealed that the Haevo and Sasakolo turtles are especially at risk from long-line fisheries in the waters off New Zealand. Vessels fishing for bigeye tuna and swordfish operate in the same area of ocean where at least six of the tagged turtles forage. A 2022 report from the New Zealand government found that between 2007 and 2021, 213 leatherbacks were caught as bycatch in the country’s commercial fisheries.

“In many cases, turtles and fishermen are looking for similar things,” says George Shillinger, the executive director of Upwell, a nonprofit that focuses on at-sea threats leatherbacks and other turtles. “The same things that aggregate zooplankton that turtles feed on, like eddies and convergence zones, also aggregate large fish that are targeted by commercial fisheries.”

“The population is so fragile that it can barely handle the loss of a single turtle.”

George Shillinger

Given the small size of the nesting populations at Haevo and Sasakolo — just 10 to 20 turtles each year — protecting each and every turtle is critical. “The population is so fragile that it can barely handle the loss of a single turtle,” Shillinger says. “We could see the extirpation of leatherbacks from the entire Pacific Ocean by the turn of the century if we don’t do something radical to stop bycatch and protect nesting beaches.”

Upwell is creating a species distribution model for leatherbacks, using satellite tracking data and data from on-vessel observers and oceanographic conditions. TNC’s satellite tracks filled a critical gap in their dataset, as it is the only telemetry data specifically showing leatherbacks targeting the eddies off the New Zealand coast. That model will then feed into a predictive tool for managers, allowing them to predict the likelihood of leatherback presence at any given time under prevalent oceanographic conditions.

The governments of New Zealand and the Australian state of New South Wales are interested in using Upwell’s models to help reduce leatherback bycatch in both longline fisheries and coastal shark nets. Upwell hopes to refine its model using data from future aerial surveys over New Zealand waters, where specially outfitted spotter planes count leatherbacks from the air.

“When you get out into the vast expanse of the Pacific, the pressures to leatherbacks come from every direction and many are enigmatic and invisible to us because we can’t monitor them,” says Shillinger. “The data that TNC provides is helping illuminate their habitat usage during a life history phase when turtles are at great risk from fisheries bycatch.”

The hope is that with more satellite tracking data, the leatherbacks from the Solomon Islands might have a fighting chance at survival.

Join the Discussion