Ohio farmer takes a whole-farm approach to conservation

During heavy spring rains, Allen Dean watched a 60-foot tree float down the creek that crosses through one of his farms in Williams County, Ohio. Dean doesn’t usually see such immense objects float by, but he is accustomed to finding large wood chunks in his fields after flooding from heavy rainfall events, and he dreads hitting them with his combine.

Fed up, Dean recently created a grass buffer strip along a half-mile stretch of the creek in an effort to reduce flooding, remove invasive species and improve filtering of surface run-off water. He removed densely packed honeysuckle bushes that water easily rushed under and reseeded the area with grasses. The buffer area slows water movement down in both directions, potentially reducing flooding as well as soil and nutrient loss from his farm.

“I’ve wanted to clean this up for years and years,” Dean says, recalling how gullies washed out from the banks and sandbars formed in the creek during heavy rains in his youth. Now, “we’re able to hold the banks of the creek really well, just because we have sod in place.”

Creating a grassy buffer area along the creek is one of several edge of field practices Dean has implemented to better manage water and filter nutrients and sediments from water leaving his fields. It’s especially important in the area he farms in northwest Ohio, which drains into Lake Erie. Harmful algae blooms, partially attributed to nutrient loss from farms, are a chronic problem in the region.

Partnering with Ohio State U

Dean has also partnered with Ohio State University (OSU) to install a drainage water management system and a phosphorous filter that captures the nutrients out of his tile drainage system before discharging run-off water into the creek.

These edge of field practices work in tandem with Dean’s infield practices of no-till, cover crops and nutrient management, for a whole farm approach to conservation. Dean, in fact, has been a no-till farmer for 42 years, and for more than a decade, he has kept his farm covered with a living root year-round. He also runs a cover crop seed business.

“I try to do what I can on my part of the ground to make sure that we’re not allowing soil and nutrients to get back into that creek. It’s just the thing to do,” says Dean, who grows soybeans, wheat, barley, triticale and rye on 1,800 acres.

Dean has also practiced the 4Rs of nutrient management—applying the right source of fertilizer at the right rate and the right time in the right place. The 4R approach is a science-based framework for optimizing nutrient use, sustaining crop production and minimizing nutrient loss from the fields, while considering specific individual farms’ needs.

Dean has also practiced the 4Rs of nutrient management—applying the right source of fertilizer at the right rate and the right time in the right place. The 4R approach is a science-based framework for optimizing nutrient use, sustaining crop production and minimizing nutrient loss from the fields, while considering specific individual farms’ needs.

Working with Nestor Ag, LLC, the first independent crop consultant operation to earn 4R Nutrient Stewardship Certification, Dean has strived to apply only the necessary amount of nutrients where needed, thereby reducing costs and the potential for excess nutrients and fertilizers to flow into waterways via tile or surface water runoff.

“We have actually seen a reduction in the amount of nutrients we’re having to apply with our fields because of the way we farm, especially with cover crops” Dean says. “As long as we have a cover crop out there, we just don’t get much erosion anymore at all, even at large rainfall events.”

“We have actually seen a reduction in the amount of nutrients we’re having to apply with our fields because of the way we farm, especially with cover crops” Dean says. “As long as we have a cover crop out there, we just don’t get much erosion anymore at all, even at large rainfall events.”

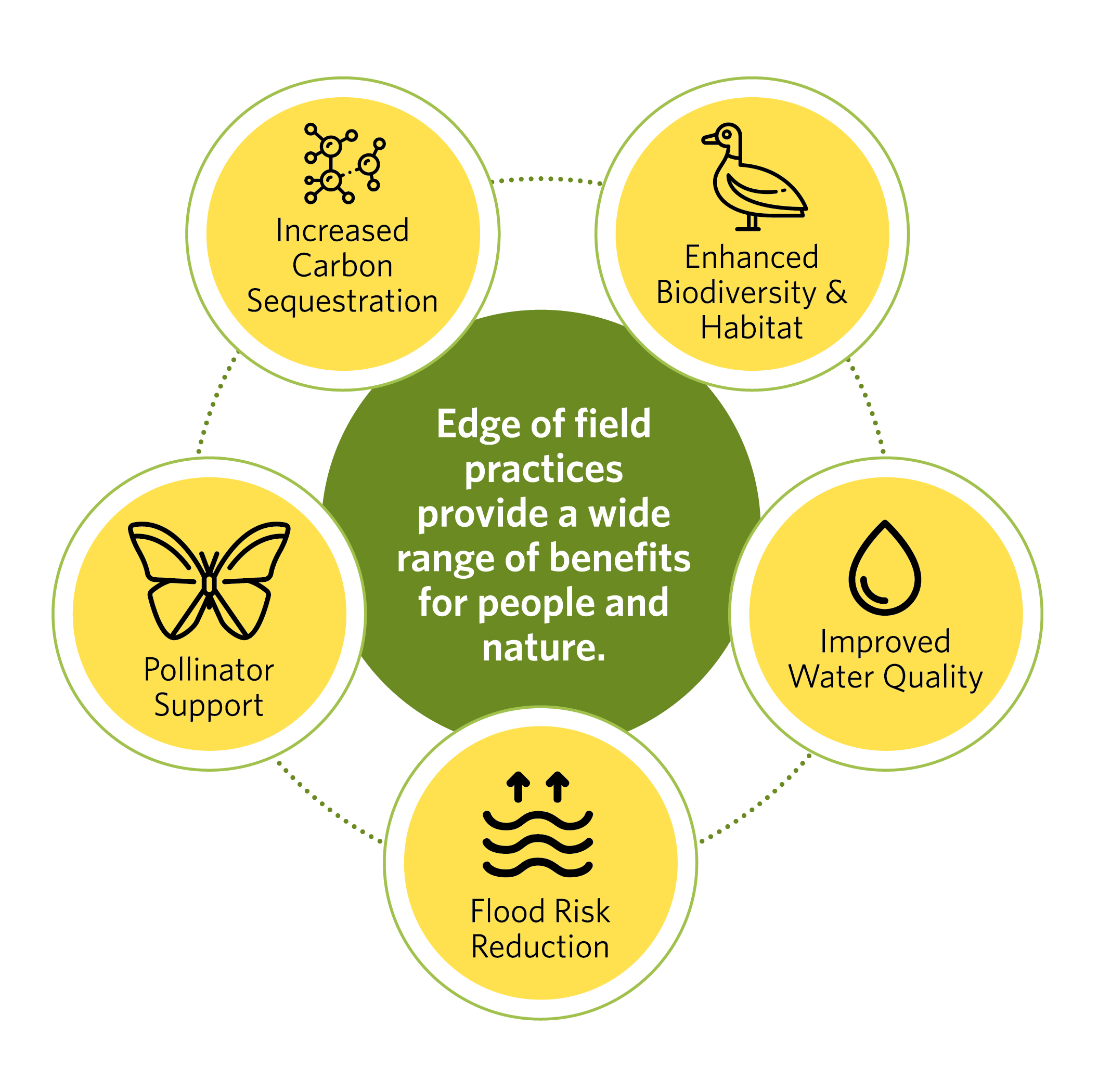

Edge of field practices play a huge role in farm stewardship and farm productivity, says Brent Nicol, agriculture conservation practitioner for The Nature Conservancy in Ohio. They reduce nutrient runoff, which in turn improves water quality, reduces flooding, and enhances wildlife habitat. “Long-term farm sustainability is really only achieved when edge of field systems, combined with in-field soil health and nutrient management practices, are incorporated into the operation,” he says.

Maximizing Edge of Field Practices

Nathan Stoltzfus, project engineer at OSU, is helping Dean optimize his drainage management system. This form of edge of field practice uses control structures on subsurface tile outlets (e.g., for subsurface tiles) to manage water drainage from fields throughout the year. Growers use these control structures to manage the water table in the field and only use the tile system to drain water from the field during needed times of the year.

During the winter the control structure will turn off the drainage system to allow more of the soil profile to store water, as drainage is not typically needed during this time of year. To allow for spring and fall field operations, the control structure will allow the field to fully drain, while during the growing season the water table is raised up to root zone. Drainage water management can cut nitrate loss from fields by 33% and modestly boosts crop yields, though it may increase the potential for soil erosion when water levels are high. Complementary in-field practices like no-till and cover crops minimize that potential.

Stoltzfus studied the hydrology and drainage patterns for several of Dean’s fields with a higher risk for nutrient loss before putting in the control structure on the existing tile.

Stoltzfus studied the hydrology and drainage patterns for several of Dean’s fields with a higher risk for nutrient loss before putting in the control structure on the existing tile.

Describing how the system works, Dean says, “They drop the boards and the little structures to stop the water flow out of the field and let it stay back into the field for the crops that are growing [when it’s dry]. And then usually in the spring and probably in the fall, they’ll pull those boards up and allow all that water to flow on through. That way it doesn’t interfere with planting or harvesting.”

Stoltzfus also created a phosphorus filter system for Dean’s farm on an existing grass buffer using a mixture of steel shavings and pea gravel to capture the phosphorus. Phosphorus filters installed at the edges of fields contain a material inside that chemically reacts with phosphorous dissolved in the water to prevent it from leaving the farm. OSU research shows they have the potential to remove up to 75% of the phosphorus in the water that passes through them. When connected to a subsurface drainage system, phosphorus filter media can be placed in a large concrete tank or in a large, buried bed.

“It is really a great way to get phosphorus out using what is a pretty cheap and readily available material,” Stoltzfus says.

Other edge of field practices include:

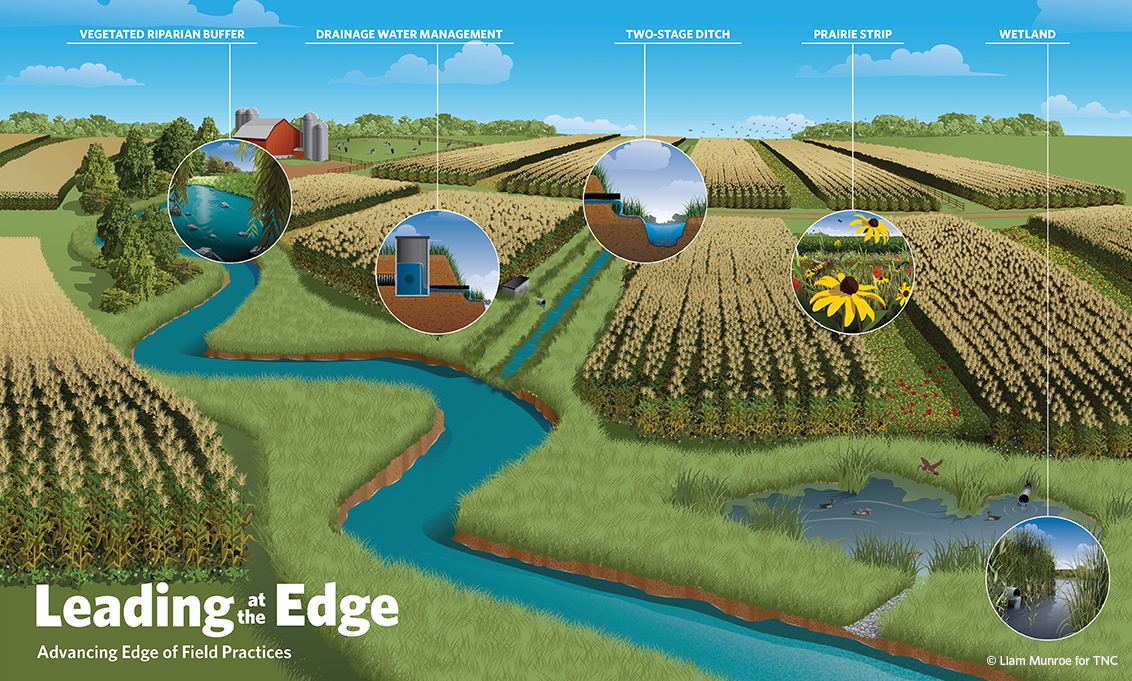

- Vegetated buffers or field borders, like the grassy area Dean created, provide a transition zone between the crop field and a waterway. The roots stabilize stream banks and reduce erosion, while filtering sediment and absorbing nutrients from surface water flow off the farm. Ideal buffer areas contain a diverse mix of native grasses, though a simple grass border can provide substantial benefits as well.

- A two-stage ditch is a trapezoidal drainage ditch with added floodplain benches that are vegetated to slow water flow, retain sediment and nutrients and stabilize banks. The middle channel is for low flow, while the vegetated benches absorb flooding at higher flows.

- Prairie strips are integrated within crops or planted at the edge of crop fields to reduce nutrient and sediment loss while benefitting birds, pollinators and other wildlife.

- A constructed wetland is an engineered ecosystem designed to optimize specific wetland characteristics and functions to improve water quality. “Wetlands are like the kidneys of edge of field practices,” says Nicol. “They filter out all the bad.”

Getting Advice on Edge of Field Practices

Stoltzfus advises farmers to first identify “critical source areas,” or areas of their farm that are closer to a receiving body of water and that have a higher nutrient level in the soil, perhaps from past farm management practices. “Look at your fields, not just for where you have nutrient deficiencies, but also where you might have areas that have [nutrient levels] well above what’s needed for crop production,” he advises. Then, focus on where the water is going in those fields to determine whether you might have some critical source areas.

Nicol further advises farmers to look at their yield data to identify fields that have a negative return or are on less productive ground. Edge of field practices, combined with in-field regenerative practices, could help make those acres more profitable for the farmer, reduce nutrient loading and create some wildlife habitat as well, he says. Nicol is collaborating with a nutrient service provider to analyze five years of yield data in Ohio and says he frequently sees “little pockets of the field, sometimes at the edge, sometimes right in the center,” that consistently lose money every single year. A wetland or other edge of field practice could be a good use of that land, he says, and there are state and local resources to help farmers with both technical assistance and cost sharing.

Wetlands and other practices are subsidized through the USDA’s Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program (CREP). “Why not get incentive payments rather than lose money on an acre?” queries Nicol.

For more information on edge of field practices, growers can consult their local Soil and Water Conservation District or Farm Service Agency, or USDA Natural Resource Conservation Service agent.

As for Dean, he’s pleased to be working with OSU. “We want to have an impact on our environment,” he says. “We want to do the right thing, the positive thing, and that’s been my focus all my farming career.”

Join the Discussion