Imagine tug of war. With fish. On a boat in rocking waves.

To the uninitiated, it doesn’t look like it will work. At least, not at first.

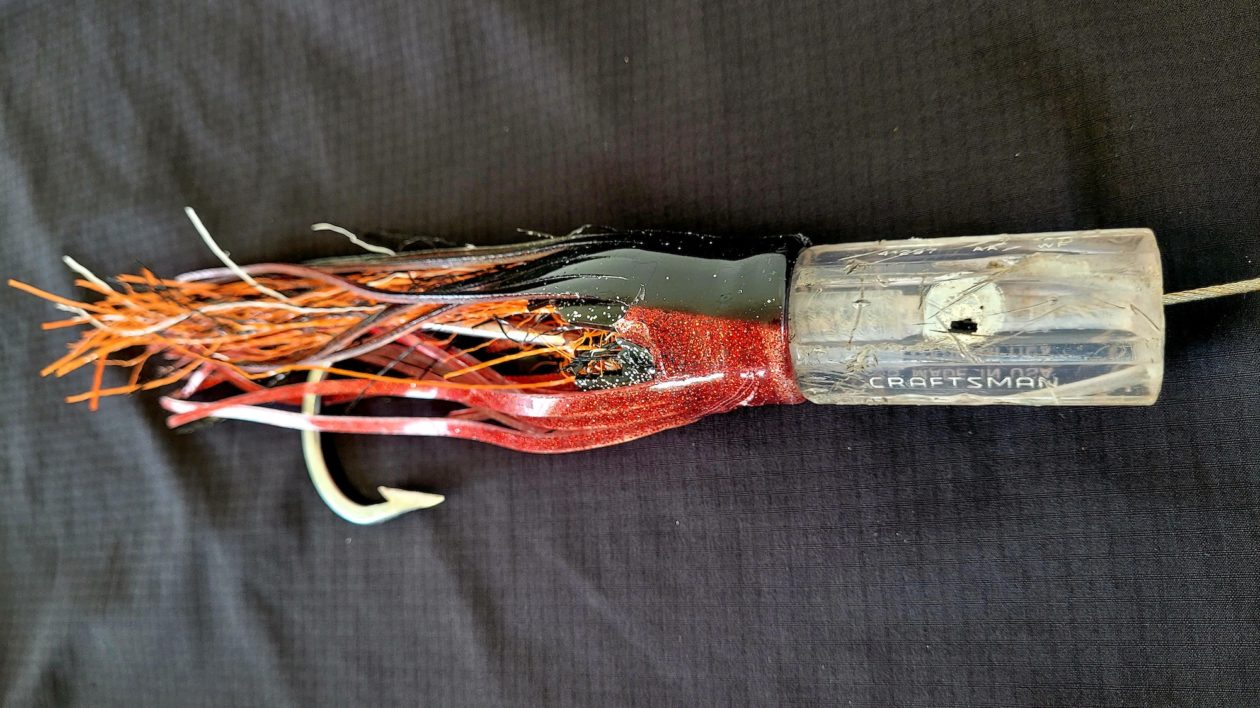

You begin by letting coils of rope roll out the back of the boat. It’s a lot of rope, quickly unwinding into the blue. At the end of the rope is a bungee cord, to which is attached standard (if super-sized) fishing gear: swivel, monofilament leader, lure.

By the time the whole contraption is out there, you can make out the lure occasionally skittering across the surface.

How will you know when a fish is on?

“You’ll know,” says Kydd Pollock, fisheries science manager for The Nature Conservancy and research leader for the Fishing for Science program at Palmyra Atoll.

You don’t have to wait long. Within minutes, there’s a boil and the rope goes taut. You lift up on the rope and feel the heavy, pulling weight of a fish. The thought is there again: will this work?

You begin to pull, fully engaged in the tug of war. But what once seemed difficult now seems much less so. The fish tires against the rope. You pull it up alongside the boat, and your teammates are by the side, ready to tag the fish for science.

How Scientists Fish

Fisheries biologists use a variety of methods to catch their research subjects. In rivers and streams, electrofishing – sending electric currents through the water to temporarily stun fish – is common. In other situations, various forms of nets are utilized. But, sometimes, the “hook and line” favored by recreational anglers also works well for research purposes.

I’m on Palmyra Atoll, a remote island 1,000 miles south of Hawai‘i, participating in a Fishing for Science trip. (For more details on this program, see my previous feature). We’re tagging bluefin and giant trevally, and by conditions of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service permit, only hook-and-line methods are allowed.

On Palmyra’s lagoons, we use rod-and-reel setups familiar to any sport fisher. We troll, cast lures and fly fish. But the reef surrounding Palmyra presents a special set of challenges. It’s here where the hand line comes in. Hand lines forego the rod and reel: they generally consist of the line and a hook. This method is used by subsistence fishers all over the world. Visit any fishing pier along the coast and you’ll see someone with fishing line attached around a stick or a Coke bottle.

On Palmyra, we use hand lines on steroids. It’s a method developed by Kydd Pollock. And it has its origin not in fishing for science, but in fishing for dinner.

The Shark Challenge

Palmyra Atoll has no permanent inhabitants, but it is home to a well-established research station. This is the base for visiting researchers as well as seasonal staff from The Nature Conservancy and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. This means sufficient food must be transported to the island from Hawai‘i, and sometimes only arrives once a month.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the agency that administers Palmyra, allows a strict quota of three fish ( wahoo or yellowfin tuna) to be harvested each week as food for the research station staff and visitors. This is a welcome source of protein and tasty, healthy meals.

Wahoo and tuna are found offshore in the pelagic environment and near the reef drop-off. They are known for being hard-fighting fish. Pollock, who grew up on a sport charter boat, is an expert in catching these species. But soon after he began the sustenance fishing, he faced a challenge.

Sharks. Lots of sharks.

“The ecosystem is so healthy at Palmyra that there is an abundance of predators, including gray reef sharks,” says Pollock. “That’s what makes it such a special place. I knew how to catch tuna and wahoo, but I quickly learned it was nearly impossible with so many sharks.”

With a rod-and-reel, the fish’s fight can last a while. The fish takes out line, the angler regains some, and the battle continues. The abundant sharks quickly keyed in on the struggling fish.

“You just couldn’t get them in quick enough,” says Pollock. “There was no way. I gave up the rod-and-reel attempts very quickly.”

As is the case with many avid anglers, Pollock is constantly tinkering with tackle arrangements. He had substantial experience with a form of hand line: He tagged more than 2,500 sharks at Palmyra using the method. But sharks are chummed close to the boat and the baited hand line is just dropped overboard. With species like wahoo and yellowtail tuna – caught using lures – the line had to be farther from the boat to avoid spooking fish.

Pollock got to work on building a better hand line. And quickly found that this method needed lots of refinement. “The strike of these fish is so powerful, it revealed every weakness in the fishing gear,” he says.

Building a Better Line

The rope used in a hand line helps bring a fish to boat quite quickly. That’s because a rope doesn’t have the give of a fishing rod and light line. But the lack of flexibility is also a liability, as any recreational angler will recognize.

A standard-issue fishing rod – any you buy at your local tackle shop – is designed for flexibility. A rod bends. If it didn’t bend, the strike and fight of a fish would break it. Or break the line. There needs to be give. That flexibility, though, is what gives a fish a “sporting chance” at getting away.

The hand line was designed to reduce fight time. But that also meant removing flexibility. So Pollock saw tackle fail. Lines broke. Swivels broke. Hooks straightened out.

“I was using 600-pound mono for the leader, and it was breaking at the swivel,” he says.

To solve this, he installed a bungee cord between the rope and leader. This absorbed the shock of a smashing fish bite, without sacrificing the ability to pull in a fish quickly. He upgraded to the strongest ball bearing swivels and big-game trolling hooks available.

Now he just needed lures that withstand the punishment. And one night in the Palmyra maintenance shed he hit upon an idea: screwdrivers.

“I needed something that would catch a fish and that was available to me,” he says. “I took an old, rusted screwdriver and pulled the driver out of the handle. I attached tassel material from lawn chairs to the screwdriver handle. It was so effective on wahoo and they were really durable. One of these improvised lures caught 40 or 50 wahoo.”

Hand Lining For Science

The hand lines worked well for sustenance fishing. Now Pollock realized they could work for the science program, too. The Fishing for Science program was having success tagging trevally in Palmyra’s lagoons. But there was a large fish population on the outer reefs. Catching them presented the same challenges with sharks.

“I knew we could tag a lot more fish if we could target them outside the reef,” Pollock says. “We could get hundreds of more tags out. But if you hook a trevally near the reef, you need to get it away from the reef right away, or it will break you off. And you need to get it away from sharks.”

The hand lines proved equally effective for trevally, as did the lures. “Trevally actually aren’t picky about what they bite,” Pollock says. “There are a lot of hungry mouths around Palmyra. When there is prey available, the fish can’t dilly dally. They strike quickly.”

This was proven during our time on Palmyra. We often fit hand lining in when we had other duties, like recovering drifting commercial fishing gear (see previous story) or deploying underwater cameras. While hand lining with a rope is not the same as angling, it is nonetheless filled with excitement and very effective.

On the larger offshore research vessel, Palmyra staff and interns could join us for a day of hand lining, a great opportunity to vary the routine, have some adventure on the seas and contribute to the scientific program.

At first, many look at the rope contraption and it all looks very complicated. That was my first response. And to be sure, pulling in the rope, while the boat rocks with waves, takes a bit of coordination that caused my clumsy self to stumble and fumble.

But after a few tries, the tell-tale eruption from a fish on the lure brought calls of excitement from the crew, and the fish was quickly aboard, safely tagged and released.

“These hand lines came about due to invention borne of necessity,” says Pollock. “Working in the remote environment of Palmyra often requires you innovate on the spot. This started as a way to get fresh food for dinner. But now it enables us to tag hundreds more fish for research.”

May you kindly share the whole details of the setup, tackle, line sizes, etc.?