Plastic puffins. Fiberglass terns. Mirrors wedged along sand dunes, and multi-speakers sound systems blasting seabird calls on remote, offshore islands.

These are just some of the many tools used to help restore seabird populations on islands around the world. Now, a new database of seabird restoration projects will aid these conservation efforts, providing an essential resource for practitioners working to protect the world’s most imperiled group of birds.

On an Island in the Sea

Seabirds are the most imperiled avian fauna on Earth. “There are about 11,000 bird species in our world and 300 of those are seabirds.” says Nick Holmes, a scientist with The Nature Conservancy. “Of those 300 seabird species, 100 are considered threatened on the IUCN Red List, making seabirds the most threatened of all bird groups.”

Just how and why seabirds became so threatened is due to geography and seabird natural history. Most seabirds — including 99% of threatened species — nest on islands and evolved in the absence of mammalian predators. When humans arrived with domestic animals and hitchhikers, like rats, seabirds had no natural defenses.

Decades of well-publicized conservation efforts have gone into eradicating rats, cats, stoats, foxes, mice, goats, and even snakes from islands, all for the birds’ benefit. Sometimes, that’s all the birds need. But if a species has been extirpated from an island for many decades, that ‘generational memory’ of the island may be gone, and the birds might need additional assistance to return.

“That’s where active restoration tools come into place,” says Dena Spatz, a conservation scientist at Pacific Rim Conservation. Scientists can either lure the birds back or move young seabirds to jump-start a colony.

These tools are as variable as the species they’re used to attract. Plastic or fiberglass decoys, sometimes paired with mirrors, are often used to start or reinforce a colony. Auditory attraction devices — loudspeakers blasting bird calls towards the sea — serve a similar purpose. And in some cases, scientists need to physically import birds to the site, a process known as translocation.

All these restoration techniques have a proven record of success, but implementing them isn’t as simple as copy-and-paste from one island to the next. Conservationists need the right tool, for the right species, in the right place. Funding is often tight, and with endangered species, there is little time for trial and error.

Knowing what restoration tools have worked in similar locations, or with the same species, can help conservationists increase their chances of success. “It’s sort of like football statistics,” explains Holmes. “One of the best ways to know if something is going to work is to look at every other time it’s been attempted.” Equally critical, Holmes says, is providing evidence of failures so that practitioners can avoid repeating mistakes.

Despite decades of work on seabird restoration, there was no one-stop resource where conservationists could access this kind of information. Some data might be in the peer-reviewed literature, but the details of many conservation projects end up in management documents on an organization’s server or long-forgotten archives.

“Surprisingly, there are very few global inventories of conservation interventions,” says Holmes. “We needed an inventory of projects to learn what’s been done, what worked or what didn’t, where, and why.”

A Searchable Database for Seabird Restoration

Enter the database. Holmes and Spatz partnered with the National Audubon Society, the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, the New Zealand Department of Conservation, and Northern Illinois University to establish the Seabird Restoration Database Partnership. Together, they gathered each and every example of seabird restoration they could find: from reports, peer-reviewed literature, conservation listservs and conferences, social media, write-in submissions, and conversations with hundreds of seabird experts.

“When we started, I thought we would identify a few hundred examples,” says Spatz. “Instead, we found more than 800. Even for us, it was so surprising to see that people have been using these techniques for such a long time to target a diversity of seabird species on both islands and the mainland.”

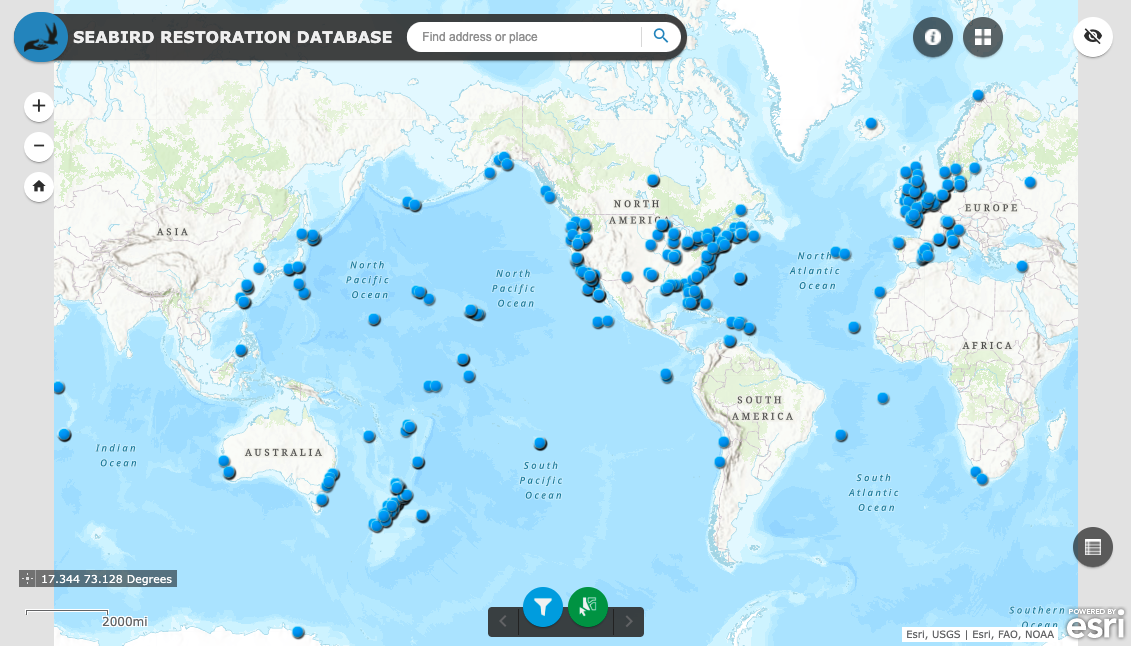

The resulting Seabird Restoration Database was published online earlier this year.

Practitioners can search restoration projects by species, geography, or restoration tools, like translocation or social attraction. Finding similar projects will help practitioners narrow in on the most effective restoration tools for their situation.

“New practitioners can get information on methods and techniques and project design, but they can also figure out who they might speak with to get more advice and input,” says Don Lyons, a seabird ecologist at the National Audubon Society. “There are so many people who have hands-on, boots-on-the-ground experience doing this work, maybe with exactly the same species, or a closely related one, to what someone is envisioning working with.”

Climate-proofing Seabirds

In previous decades, most seabird restoration efforts have focused on bringing birds back to places where they were lost, usually because of invasive predators. Now, climate change is forcing conservationists to confront a new challenge: protecting seabirds as their nesting sites are lost to rising seas. This problem calls for a more drastic solution: relocating entire rookeries to higher ground, or a different island.

This tool is already being used in places like Hawaii, where Pacific Rim Conservation and partners are relocating birds from low-lying islands at risk of inundation. “We’re moving seabirds to high-elevation mainland islands inside predator-proof fences,” Spatz says, “creating islands within islands to restore seabirds.”

Climate change is also driving the translocation of albatross from Midway Atoll to high islands in Guadalupe, Mexico. “This used to be a part of their historic range, but they were extirpated by invasive species,” explains Holmes. With the invasives removed, these new islands will serve as a refuge as the current breeding sites on Midway are lost to increasing storm surge. “Climate resiliency is coming up more and more as a new reason behind many of these restoration projects,” says Holmes.

Holmes, Spatz and their collaborators are now analyzing the database for underlying trends — why certain techniques might work in some places but not others — the results of which will be published later this year.

All of this work feeds back into TNC’s larger strategy to bolster the underlying resilience of islands, and the species that call them home. “We want to increase the scale and the pace of conservation on islands,” he says, “and one of the ways to do this is to take proven methods and replicate them in new geographies on faster timescales.”

For highly threatened seabirds, help can’t come soon enough.

The Seabird Restoration Database Partnership would like to thank the more than 350 scientists, conservation practitioners, and other experts who contributed to the database. The following organizations developed the database and created the Seabird Restoration Database Partnership: New Zealand’s Department of Conservation, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, National Audubon Society, Northern Illinois University, Pacific Rim Conservation, & The Nature Conservancy.

Really interesting , especially broadcasting different seabird calls to attract different species

I am involved in attempting to start a new penguin colony in South Africa