My friend slipped the largescale sucker in the water and it immediately swam into a deeper pool. The morning had delivered pretty much everything we could ask: beautiful weather, running water and plenty of fish. My friend, a visiting fish biologist, was thrilled to catch species new to him, like chiselmouth, largescale sucker and northern pikeminnow.

A car pulled off the road and a family spilled out. A guy approached us, a quizzical look on his face. “You catch anything here besides trash fish?” he asked, genuinely curious.

My friend started to fill him in on the morning; the guy cut him off.

“That’s what I mean. Trash fish. That’s all that’s in here,” he said with a dismissive wave.

Every spring, I fish for largescale suckers in the local creek. And every spring, I can count on hearing this.

Sometimes the onlooker goes so far as to suggest I throw them on the bank. Kill them. I’ve even heard it’s illegal to throw suckers back.

These are beautiful, native fish, important species in complex ecosystems. Where does this idea come from?

Trash fish. Rough fish. Unprotected non-game fish. This is not just a classification used by ignorant anglers. It unfortunately is also a fisheries management paradigm. There are “game” fish – intensively managed and regulated. And there are “rough” fish – fish that can often be killed in any way, without restriction. Even when doing so is not based in science. Even when it’s not based on logic.

In fact, the idea of native “trash fish” is based solely on unjustifiable cultural ideas of what fish are “good” or “bad.”

It’s time to put this outdated idea to rest. It’s time to bid farewell to “trash fish.”

What’s in A Name?

Why is the notion of “trash fish” harmful to biodiversity conservation? And why is there such a term in the first place? I’m co-author of a new paper in the journal Fisheries that delves deeply into these questions.

The study, led by the University of California, Davis, with Nicholls State University and a national team of fisheries researchers, finds that nearly all states have policies that encourage overfishing native species. Whereas limits for trout and bass have generally become more conservative, many other species can be killed without limit or reason, at any time of year. And this is solely because they’re lumped into a category of “roughfish.”

Why? For many anglers, notions of trash fish or roughfish are ingrained. The paper argues that these attitudes are not based on science. They are based on what fish have been valued historically by white, European men. The fish they considered “game” have been studied and managed.

This assertion – that the idea of “trash fish” has its roots in colonialism, racism and sexism – has drawn predictable ire on social media. Certain websites have ridiculed it. Fox News ran a segment on the paper under the headline “Woke in the Water.”

None of this changes the reality. Native “trash fish” don’t exist. It’s a human construct, based on one very specific set of cultural values. Indigenous languages don’t have a word for “trash fish.” Many cultures value fish like suckers and gar for food and sport.

As coauthor Solomon David, assistant professor at Nicholls State University, noted in the paper’s press release, ““European colonists heavily influenced what fishes were more valuable, often the species that looked more similar to what they’re used to. So trout, bass and salmon got their value while many other native species got pushed to the wayside.”

Lead author Andrew Rypel adds, “When you trace the history of the problem, you quickly realize it’s because the field was shaped by white men, excluding other points of view. Sometimes you have to look at that history honestly to figure out what to do.”

Pejorative fish names have no basis in ecology, either. The stories about gar or suckers “decimating” game fish populations are based on folklore, not fact. They serve justifications for destructive behavior, nothing more.

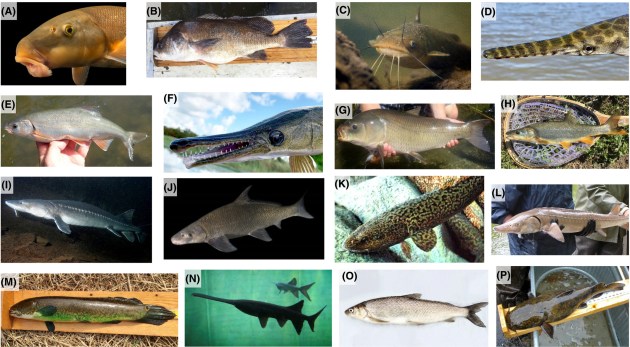

In fact, the fish clumped as “roughfish” are quite diverse and are ecologically important for many freshwater sytems. Some are apex predators. Others serve as hosts for part of the life cycle of imperiled freshwater mussel species. The gravel beds cleared out as spawning beds by several chub species are also essential for a long list of other fish species. So even the oft-derided chub is essentially an ecosystem engineer.

Words are important. As a writer, I recognize that daily. I also recognize that context matters. So I think it’s important to offer a sidenote about the use of the term “roughfish” (and similar terms).

A number of anglers have embraced the term “roughfish” to show that they appreciate unappreciated fishes. The site Roughfish.com in particular was founded on the idea that all fish have value, and that fish derided as roughfish are actually “the coolest fishes on the planet.” Such enthusiasts call themselves roughfishers with pride, and a core belief of a roughfisher is to treat all fish with respect. I count myself among their number. I’ll continue to call myself a roughfisher.

But the term “roughfish” (or “trash fish”) as a management construct has got to go. Because it never indicates respect. When you see “roughfish” in a fishing regulations booklet, it means that you can kill those fish in unlimited numbers. That’s not justifiable.

Science-Based

If you read outdoor periodicals (and I do, a lot), you will often see this phrase: “Manage with science, not emotion.” This is usually in reference to so-called ballot box biology, putting wildlife management to a popular vote. The idea is that wildlife regulations should be decided by research and evidence.

So let’s apply this to fishing regulations, because a very long list of fish species are not regulated by science. They are lumped into a category based on outdated values and folklore. For many of these species, there is very little research on what sustainable management looks like.

Some species like bigmouth buffalo and alligator gar are long-lived and slow to mature. Removing large females can have an extremely adverse impact on populations.

Bowfishing has grown increasingly high-tech, with specialized boats and lighting. The sport has exploded in popularity, but as another recent paper pointed out, regulations have not kept up.

Manage with science. That is what we are asking.

An important start would be to enact wanton waste laws for all fish species. Wanton waste laws forbid the wasting of fish carcasses that are killed. Such laws are already on the books for “gamefish” species (as well as other wildlife). I do not oppose someone keeping a few suckers to eat. But killing large numbers and leaving them to rot on the river bank is a disgusting, unjustifiable practice.

A viral video this summer showed two bowfishers counting off 1,000 gar they killed in an outing. They dumped every dead fish back into the water, a tremendous waste. Can you imagine if this was largemouth bass or walleye?

Management agencies need to step up, but I am convinced that anglers can and must play a role in native fish conservation. Anglers could be a vital force for change. And for those who think the “trash fish” moniker is too deeply ingrained for change, I disagree.

Norman Maclean’s A River Runs Through It is viewed as an almost spiritual text by fly fishers. Many believe it has substantially influenced current trout fishing ethics. Read it again. Maclean kept every big trout he caught, as did his family and friends. They filled freezers full of trout, all caught from wild Montana rivers.

Cruise along the Blackfoot and Madison today, and keep an eye out for fly anglers thumping trout on the head. You’ll be looking a very, very long time. It doesn’t happen.

The current issue of the magazine Fur-Fish-Game includes an article about historical muskie angling. As the muskie was pulled near the boat, it was shot with a gun. Every time. This was a long-accepted practice in Wisconsin and other states. There was no catch and release. That is now illegal and no one questions such a regulation.

Angling values change. Anglers recognized that wild trout populations were not limitless, that shooting muskies would soon mean no more muskies.

Many see a sucker or gar or bowfin and think of them as undesirable. But take another look: whether you’re evaluating a fish on a cultural, ecological or sporting basis, these fish aren’t trash. They aren’t being managed scientifically. It’s time for a change.

It’s time to put the term “trash fish” in the trash, where it belongs, and give these fish the respect (and management) they deserve.

All aquatic native species are essential to the maintanance of the ecosystem . The Trash species is us.

You are as ignorant as the DNR ecologists and the Professors that teach ecology at our universities. Have you ever heard of co-evolution in the streams, rivers and lakes environment? Many freshwater mussels glochidia depend on these “rough fish” for hosts. The native crayfish burrow is where the endangered Eastern massasauga Rattlesnake, endangered Blanchard’s Cricket Frog, and the endangered Emerald Hine’s dragonfly hibernate over a long, cold winter. How many of the “rough fish” are in the food chain of many fishes, birds, minks, otters, etc. in the streams, river and lakes environment?

Thanks for the article on TRASH fish. I fished Schoharie Creek in NY for carp for years and enjoyed vthe incredible fight they give but also the wonderfull taste when baked with a little tarragon or oregano and grated parm.and bread crumbs. Some people will spend hundreds of dollars to go bluefish fishing off NY when they can just make some dough balls and have some real sport right here and taste the same quality fish.

I agree with the idea that native fish that have historically been considered undesirable should be better managed when it’s needed. In many cases the lack of management is due to their undesirability, which means catch is low. For example, redfish (red drum) was considered pretty much a trash fish until Paul Prudhomme came up with blackened redfish and the fishery exploded and management had to catch up. Northern pikeminnow are considered a rough fish and bounties have been placed on them etc with virtually no effect on their populations. I don’t think this problem is rooted specifically in white male culture. In the south many black fishers will throw gars and bowfin on the bank to die in the belief that they eat bass and crappie. Every society has their preferred fish species and they get decimated. The poor management of “trash fish” is a problem worldwide – e.g. see this article about Ghana

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S016578360800338X?via%3Dihub

The native Americans valued native fishes highly (they were all they had) but probably did little if any management (exceptions would be shellfish farming etc) because it wasn’t needed given the smaller population size and low-tech harvesting techniques. Citing colonialism and race to account for what is really a complex issue is not constructive, in my opinion. Better would be to improve attitudes toward these species, and this isn’t how to do it unless you want to restrict your impact to academics.