I reeled in my lure along the river’s bank when a fish struck. I felt my usual surge of excitement as the fish leaped into the air. A largemouth bass. I felt a little deflated.

Don’t get me wrong. I enjoy bass fishing. But I was visiting a northern California river with several fascinating native species. Instead, I encountered a “game” fish far from its native range. And this seems to happen wherever I travel and fish; I encounter a predictable assortment of popular game species that have been stocked far and wide, with little regard to native fish diversity.

The truth is, most people can only name a short list of freshwater fish species, if they think about freshwater fish at all. Even many well-rounded naturalists are hard pressed to identify most fish found in local streams and rivers.

Marine fish? Sure. Most of us know that coral reefs are teeming with colorful species. We assume that the oceans are where the fish diversity is.

Consider this: Freshwater encompasses only 0.01 percent of the world’s water, yet accounts for nearly half of all fish species.

In this blog, I’ve focused on larger U.S. species. There are so many spectacular freshwater species globally, and a host of colorful and cool smaller species in the U.S. But I chose these species to show that we don’t even know many of the larger fish swimming around local waters. I also purposefully chose some lesser-known species and subspecies of familiar game fish. Even when it comes to trout and bass, most don’t the diversity that exists – an imperiled diversity, at that.

I hope you enjoy these native fish, and please share your own favorites in the comments.

-

Chiselmouth

Chiselmouth © Ben Cantrell Some freshwater fish have downright strange and unfortunate names. Chiselmouth, however, is a wonderfully descriptive common name; this fish really does have a chisel mouth. The chiselmouth’s lower jaw has a distinctive line of cartilage that it used to scrape algae and zooplankton off rocks.

The book Fishes of Idaho notes that the fish scrape their lower jaw over rocks and other hard surfaces in “short, quick movements” of about 1-inch. They then ingest what they have scraped off.

Chiselmouths are found in streams and rivers in Pacific drainages of the Northwest United States and British Columbia. They can reach one pound or more. They are abundant in places. And, despite their seemingly specialized feeding habits, they can be caught on small baits and flies. Despite all this, the chiselmouth is little known and rarely studied.

-

Hardhead

A hardhead. © Matthew L. Miller Hardheads are members of Cyprinidae, the fish family commonly known as minnows. But the hardhead is not what springs to mind when you imagine a minnow. It can reach 2 feet in length, and while it will eat zooplankton and even algae, it also hunts down crayfish and small fish.

This is one of several interesting fishes endemic to California. It is found in deep river pools, where it will aggressively nab lures and baits. You would think all this would make hardhead fishing a bucket list trip for the intrepid angler. But anglers are often not logical. In fact, hardheads are unfairly blamed for declines in salmon. There are even “derbies” that encourage people to kill hardheads and other native fishes.

I caught a hardhead in the last hour of the last day of a recent trip to northern California. It’s one of my favorite catches, a distinct fish well worth seeking. And how can you not love a fish called a hardhead?

-

Blue Sucker

A blue sucker. © Olaf Nelfon / Flickr Suckers are unfairly maligned, the subject of myth and misinformation. There are 78 suckers native to North America. Among them are some of the most endangered fish on the continent. There are also many striking species, if you take the time to get past your misconceptions.

The blue sucker is a spectacular fish. Its sickle-shaped dorsal fine and torpedo like body make it perfectly adapted to rapid currents, the habitat it requires. It migrates upstream on rivers and congregates in large numbers to spawn.

This is a fish migration that is ignored but is still a natural spectacle. And a potentially threatened one. Blue suckers need swift currents and connected waters in its range on several major rivers in the middle of the United States. Dams and diversions block fish passage and change stream flows, preventing blue suckers from reaching spawning areas.

-

Bigmouth Buffalo

A bigmouth buffalo held by Trevor Starks. © Trevor Starks Here’s another fish with an (angler) identity crisis. Many believe this fish resembles a carp, a non-native species. But bigmouth buffalo are native. And there’s more than mistaken identity at stake.

Recent research has found that bigmouth buffalo can live more than 100 years. They breed intermittently rather than annually. This makes them potentially vulnerable to overharvest, particularly if mature females (the largest fish) are killed. Unfortunately, most populations of bigmouth buffalo are essentially unmanaged – people can shoot them with bows in many states without limit. And they might do so erroneously believing they’re controlling invasive species.

On a recent episode of the popular fishing show Das Boat, buffalo biologist Alec Lackmann says “Calling a buffalo a carp is like calling a human a lemur,” an implied reference to the evolutionary distance between the two groups. Yes. Anglers need to learn to identify native fish. Agencies need to manage all species, not just gamefish. And all of us need to speak up for the buffalo.

-

Hornyhead Chub

© Reuven Martin / Wikimedia Commons It’s difficult to imagine a more undignified common name than “hornyhead chub.” The fish gets its name from the tubercles – noticeable bumps – that appear on the head of a breeding male. These tubercles appear on other chub species as well, leading to a lot of species confusion.

Name aside, hornyhead chubs are important for stream ecosystems in the Midwest. They clear out a gravel redd for spawning. This gravel is used not only by the chub, but by a number of other species as well. This is true for other chubs. The bluehead chub of the Southeast United States is a true ecosystem engineer, an unappreciated species that contributes significantly to biodiversity. Look for a feature on the bluehead chub in an upcoming feature on Cool Green Science.

-

Sacramento Perch

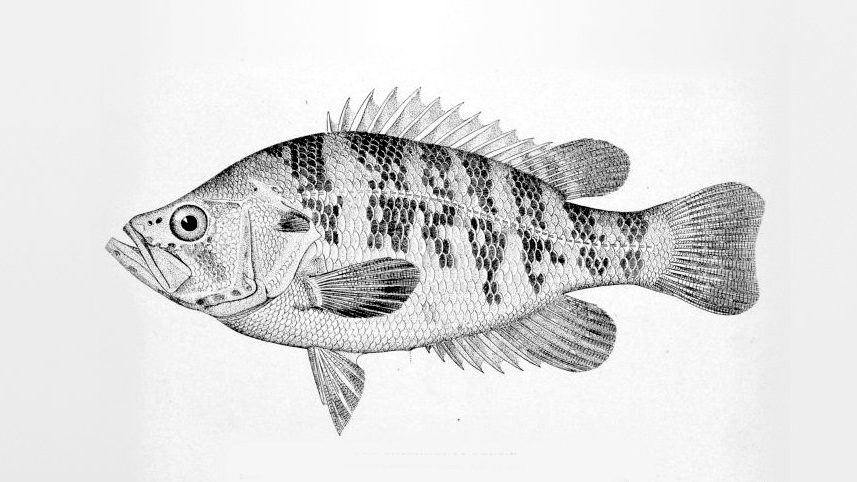

© HL Todd / Wikimedia Commons The sunfish include some of the most recognized fishes in North America. Their family, Centrarchidae, includes such angling crowd pleasers as the bluegill, redear sunfish, black crappie and largemouth and smallmouth bass. Many of these species have been introduced widely around the globe. But even among the sunfishes, a number of species are poorly known.

The Sacramento perch is actually the only centrarchid found west of the Rockies. It bears some similarity to the rock bass, a familiar species in the East and Midwest, with white and black barring. This is another California specialty. Unfortunately, the combination of water diversions, water quality issues and introduced species (including non-native sunfishes) has spelled doom for the Sacramento perch. Most sources state that it has been extirpated from its native range.

But just as people moved bass into the Sacramento perch’s habitat, they transported the Sacramento perch to other waterways. They have been introduced to Colorado, Nebraska and other states, but most of these introductions have fared poorly. However, several lakes and rivers in California and surrounding states have stable or even thriving Sacramento perch populations.

-

Redeye Bass

© Mike Cline / Wikimedia Commons How can there be a bass on this list? Everyone knows bass, right? It’s true that largemouth and smallmouth bass are the most popular sport fish in the United States. But there are other bass than these. For me, the habits and habitat of these overlooked bass make them fish of dreams.

Redeye bass live in upland streams in Georgia, Alabama and South Carolina. Their small size and stream habitats mean they are out of sight and out of mind for the bass tournament crowd. But they are beautiful fish with striking color patterns.

Recent research suggests the redeye bass actually consists of up to 7 species, each restricted to specific watersheds. This diversity could be lost before we even fully understand it, as stockings (often illegal) of other bass in their waters threatens the native redeyes with hybridization.

Fortunately, there is a growing appreciation for these fish, with a great book on fly fishing for them by Matthew R. Lewis, a Georgia Bass Slam that celebrates catching of native bass and a popular Facebook page educating anglers and naturalists about these fish.

-

Bonneville Cisco

© Redmustang01 / Wikimedia Commons North America has some lakes that are largely isolated from other waterways, allowing fish to evolve to fit unique niches. Such isolated waters are also very vulnerable to invasive species and other threats, a clear example of island biogeography (a large and connected habitat and its species are more resilient to threats than a small, isolated one). As such, endemic species in lakes are often gravely imperiled. Or extinct.

Bear Lake, straddling the Idaho-Utah border, is known for its Caribbean blue waters. It is also home to four fish species found nowhere else on earth: the Bear Lake sculpin, Bear Lake whitefish, Bonneville whitefish and Bonneville cisco. But unlike many isolated lakes, Bear Lake has never had a significant problem with invasive species.

So Bear Lake’s endemic fish still thrive. In fact, there are fishing seasons for three of them. The most famous is the Bonneville cisco. Each January, Bear Lake hosts the Cisco Disco, where people can catch ciscoes using dip nets. Hosts serve fried cisco to visitors, and there are various festival activities. I enjoyed catching and dining on cisco but passed on the polar bear plunge into the lake’s icy waters.

-

Willow-Whitehorse Cutthroat

Willow-Whitehorse cutthroat. © Matthew L. Miller In my obsessive pursuit of weird fish in weird places, I can count on one thing: Someone is going to ask “Are there actually fish in there?” That was the case as I walked with a fly rod through the eastern Oregon desert, a land known for alkali flats and expansive sagebrush, not trout streams.

But I was seeking the Willow-Whitehorse trout, considered by trout expert Robert Behnke to be a separate subspecies and by others to be a stream-form of the Lahontan cutthroat. Either way, this trout is found in just a couple isolated desert waters. These are tiny streams, but the fish I caught were a foot or more with a deep pink color.

Trout, of course, have been stocked widely around the globe, at the expense of other fish. Including other trout. Beautiful native trout species and subspecies have disappeared in the onslaught of hatchery rainbow trout, brook trout and brown trout introductions.

The Great Basin of Idaho, Nevada and Oregon still contain some stunning native trout varieties. These trout have adapted to life in the desert and are able to withstand higher water temperatures. This has made them less susceptible to non-native introductions. Even here, non-native trout can dominate, but in remote streams, you can still find some gems. Like the Willow-Whitehorse cutthroat.

There are so many great native fish across North America, and too few native fish advocates. That is fortunately changing. Groups like the Native Fish Coalition, North American Native Fishes Association and Roughfish.com argue that all native fish have inherent value.

Photographer Joel Sartore has highlighted many freshwater species in his Photo Ark that documents the world’s biodiversity. And a cadre of fish biologists and fish nerds are sharing the coolness of all things finned on Twitter and Instagram. Whether with a snorkel, a fishing rod or a naturalist’s eye, take a minute to learn more about your local stream. Then join the important work of protecting and preserving our freshwater biodiversity.

Great article. There are a number of other cool freshwater natives that make me smile and are important. The Goldeye and the Mooneye are remarkable shad-like superstars and cool to see and catch (and release.) Sculpins are way cool. Fres water ling in North Idaho! Catfish are under appreciated by some but are amazing animals. I love the anadromous shad migrations and fishing in the Sacto River. Thanks for shining a light on the natives that are not trout and bass.

For Annie Stratton……there is probably a Trout Unlimited chapter near you. Their main directive is to preserve cool, clean water(s) for the continuation of all species. TroutUnlimited.com.

Well done and fun to see those natives—Diversity is good for people and wildlife.

Loved the article! I live near the Kansas City Missouri area so unfortunately very few of the species you wrote about are near me. I have however caught A couple Hornyhead Chub during a trip to Missouri a year or two ago. And hopefully this year I will be checking Bigmouth Buffalo of my life list. Your section on the Hardheaded was especially intriguing to me. The Hardhead seems like it would be such a blast to fish for using light tackle just like Creek Chubs. The two fish don’t seem to different which is why it caught my attention. I love to fish for Creek Chubs by the way. Thanks for showing the fishing community how cool these poorly known fish are!

Wonderful article. My family when I was growing up in southern Oregon fished- a lot. I wasn’t a fisher, preferring to go along the shores of lakes and streams turning over rocks and drawing what I found (I’m too wiggly myself to be a good fisherwoman). But I loved the fish. They are so beautiful- the graceful shapes, the setting of the fins, the often subtle coloring. Even the oddballs are beautiful.

I so enjoyed reading this article, and immediately recognized a couple of the fish you identified as from the area my family fished. But I never knew what most were called, and am sitting here astonished at that! I need to change that. I still (now in Vermont) like to watch fish in streams. I don’t even know if they are native or stocked, but suspect that often the latter is more likely- except maybe for those isolated ponds and small streams in the mountains. What an excuse to go hiking.

Vermont has an association for all kinds of creatures, loves its waters, so my bet is there’s a group of native fish lovers out there. So I’m setting myself a task: joining up.

I worked with a team of fish biologists in New Mexico for awhile and I can’t tell you how many people asked me, “are there really fish in the desert”? YES, and they are AMAZING because they have had to adapt to very stressful and often isolated habitats. I don’t know if you’ll ever find anything as mysterious as the Devil’s Hole Pupfish, which exists in one cave in the Mojave desert and whose entire population has hovered below 100 for years. We have much to learn from fish species that have adapted to harsh environments. h ttps://www.fws.gov/nevada/protected_species/fish/species/dhp/dhp.html

Sara,

Many thanks for commenting. I visited Devil’s Hole with TNC’s Sophie Parker several years ago. We were not able to see the pupfish through the fence, but what a spectacular place. We were able to see other pupfish species at Ash Meadows National Wildlife Refuge and Death Valley. There is also a wonderful book on desert fishes (including pupfish), Relicts of a Beautiful Sea by Christopher Norment.

Best,

Matt

Thanks for the article. I live in the center of Illinois surrounded by many major rivers and streams and enjoy finding different information about our wildlife. Maybe sometime you could visit around the area and write a informative article for our knowledge. Thanks, James Blunt Oakley IL