Linda Reinhold was hiking through the Australian rainforest in search of mushrooms when she saw something small and glowing dash through the beam of her UV flashlight.

Another one skittered forward, pausing long enough for Reinhold to identify it as an antechinus, a mouse-like marsupial. Under normal light, its fur was a soft brown. But when she switched to her UV light, the antechinus glowed bright white, like a fuzzy glowstick.

“Just a few minutes earlier I’d found the biggest bunch of ghost mushrooms I’d ever seen, so when I saw the fluorescent mammals I wondered if I’d accidentally licked my fingers or put my hands in my mouth,” she said. “I thought there was an 80 percent chance I was hallucinating.”

But she wasn’t hallucinating.

The antechinus were glowing in the dark. And they’re not alone. Scientists are discovering dozens of mammals that glow under ultraviolet light, from flying squirrels to wombats to African springhares.

A Kaleidoscope of Color

The animal world is full of color, but these hues are created with very different mechanisms. Many animals, including humans, derive their color from pigments in their skin or hair. Melanins are one of the more common pigments, which is why so many mammals are various shades of brown.

Other animals derive their color from pigments in their diet. Flamingos and house finches get their red coloration from the shrimp or plants they eat, which contain carotenoid pigments that accumulate in the birds’ feathers. Other animals — like chameleons, octopus, or cuttlefish — can change their color using pigment-containing cells called chromatophores.

Critters with structural color have feathers or a carapace covered in microscopic structures that reflect light. These creatures often have a metallic or iridescent sheen, like blue-green beetles or the purple-green shimmer of a grackle’s wing.

Bioluminescent animals — like glow worms, anglerfish, or phytoplankton — or produce their own light through a chemical reaction within their bodies. Biofluorescent animals have fur or skin that absorbs short-wavelength light (ultraviolet) and re-emits it as longer wavelength (in the visible spectrum) that humans can see. Biofluorescence is common in invertebrates, reptiles, amphibians, fish, and even birds. Puffin beaks glow pink and white under UV light, and so do owl wings and budgerigar facial feathers.

And, as scientists are now learning, biofluorescence is more common in mammals than we realized.

Dim the Lights

After discovering the glowing antechinus — and confirming that she wasn’t on an accidental ‘shroom trip — Reinhold spent three days driving around the Far North Queensland forests looking for roadkill. She found and photographed both bandicoots and platypus fluorescing under UV light.

Then she dove into the scientific literature. Reinhold says that the first known report of mammalian biofluorescence dates to the 1940s, when an Australian scientist published an observation that brush-tailed possums glowed under UV light in the final days of World War II, writing that the phenomenon was “not uncommon in mammalian hair.”

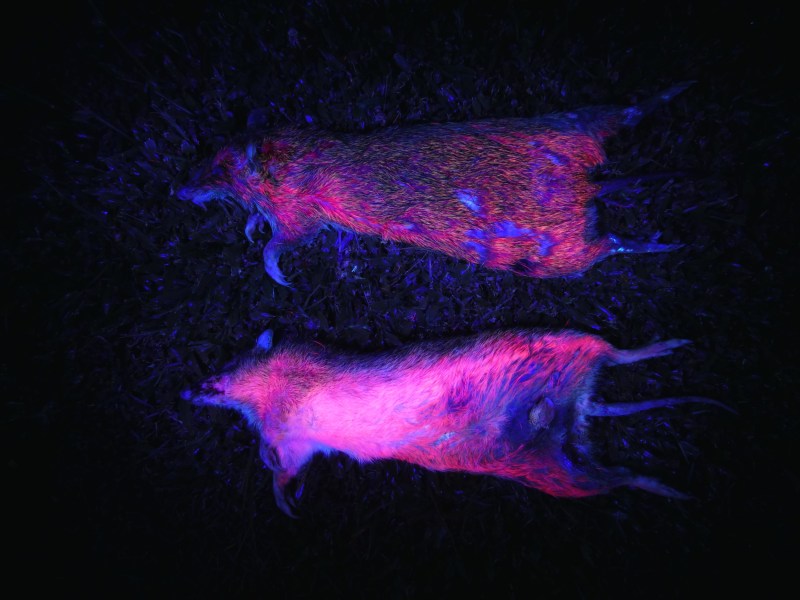

In the 1950s, scientists noticed that their lab rats glowed, while still more research from the 1970s and 80s documented biofluorescence in tree kangaroos and New World marsupial opossums. But the phenomenon remained little-known and under-studied, even amongst serious naturalists, until the past few years.

“It is likely because our understanding of how different species interact with different wavelengths of light has only grown over time, and because hand-held UV lights were not that common or accessible a few decades ago,” says Erik Olson, a scientist at Northland College. “Now I can order one to show up on my doorstep within a few days.”

Olson and his team have been leading the recent resurgence into mammalian biofluorescence.

It all started when another colleague, Jonathan Martin, was exploring his backyard at night and noticed the flying squirrel munching on his bird feeder glowed pink and blue. That led to the discovery that New World flying squirrels fluoresce on their underbellies. The three species in the Glaucomys genus are found across the eastern and central United States, Canada, and southern California.

Olson’s team also discovered that African springhares, which look like a cross between a bunny and a kangaroo, have fur that glows with patches and swirls of pink and orange. The two species, Pedetidae capensis and Pedetidae surdaster are the sole members of their genus.

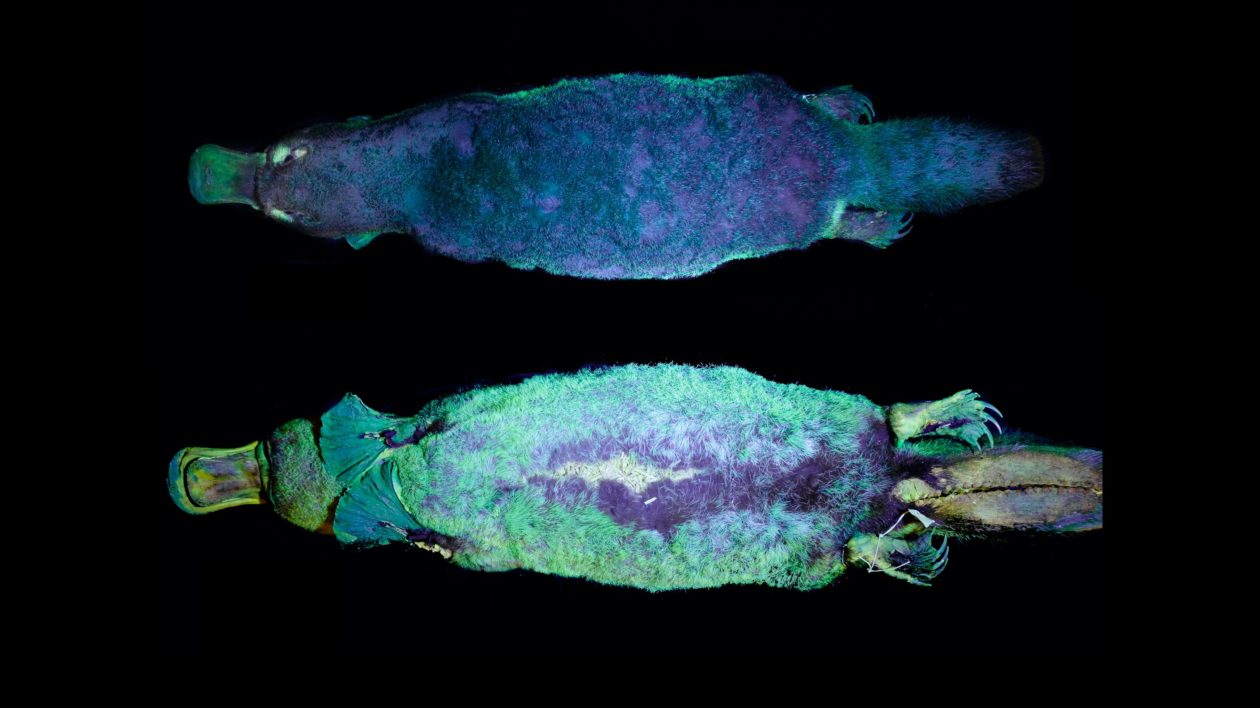

And Olson’s colleague, Paula Spaeth Anich, found that platypus specimens from the Chicago Field Museum glowed blue and green, just like the roadkill platypus Reinhold photographed in March 2020.

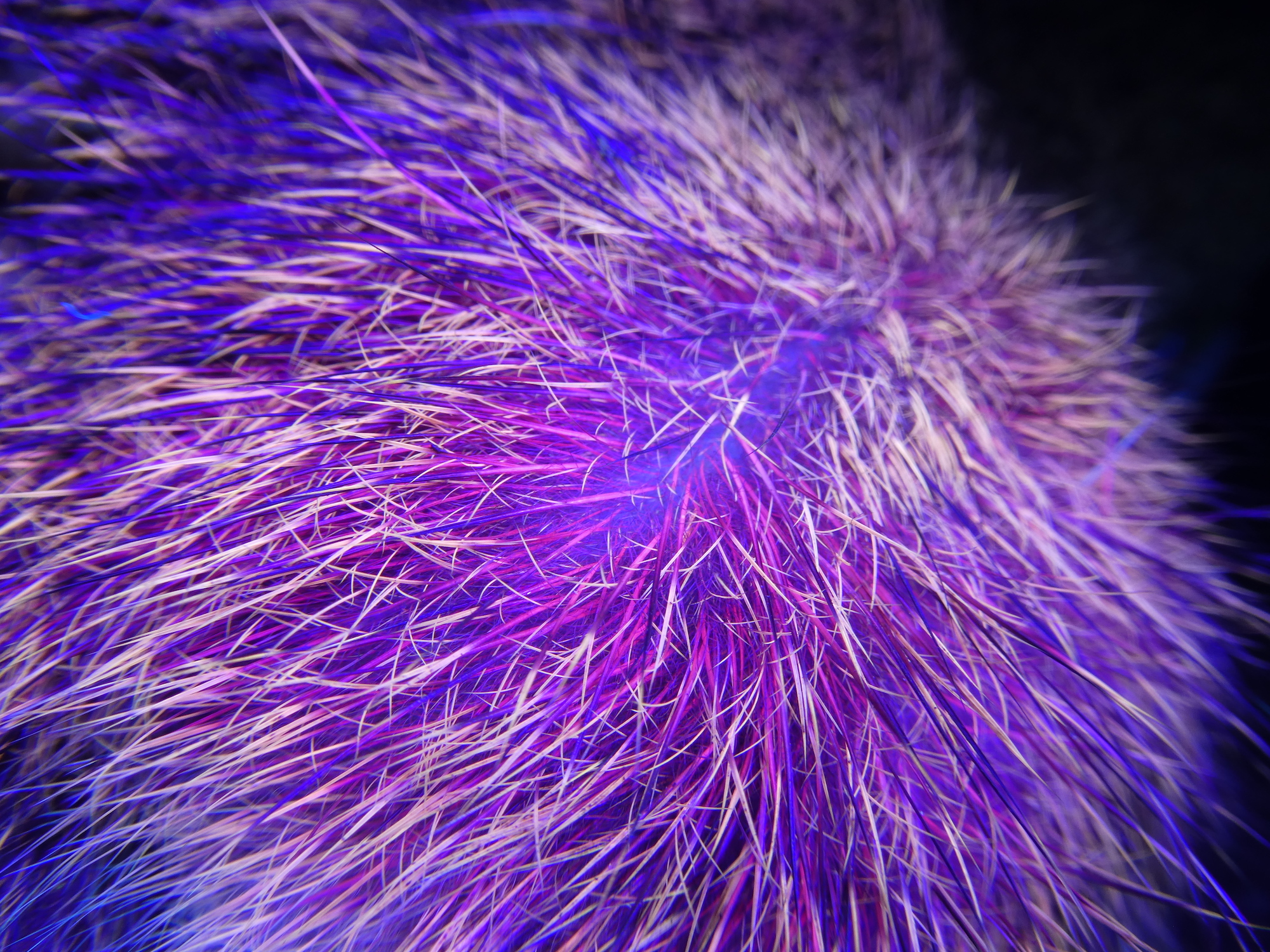

Soon, other scientists were ordering UV flashlights and going on a treasure hunt through their local museum collections (or zoos). Kenny Travouillon, the curator of mammalogy at the Western Australia Museum, found glowing greater bilbies (white ears), ghost bats (golden yellow wings), Tasmanian devils (blue ears, eyes, and teeth), and echidnas (white spines).

And Reinhold, who is now working towards a master’s degree studying mammalian biofluorescence, discovered that striped possum and Krefft’s gliders glow blue-white, while long-nosed bandicoots glow “knock-your-eyes-out bright pink.”

Unanswered Questions

At this point, scientists have more questions about mammalian biofluorescence than answers. When did it evolve? Why do mammals glow? And can they see one another?

Not all mammals glow, but it seems the trait is more widespread than we realized. And the fact that both monotremes and placental mammals on multiple continents glow suggests that biofluorescence might be an ancient mammalian trait.

As to why they glow, Olson and his team suggest a number of possibilities. UV reflectance could be a form of camouflage, creating “visual noise” to confuse predators who are sensitive to UV light.

Or it could be a way for some species to rid themselves of dietary toxins by depositing the harmful chemicals in their fur. Olson discovered that the African springhares’ pink-and-orange coloration is produced by organic compounds called porphyrins.

“In humans, excess porphyrins are associated with the disease porphyria,” says Olson, “however, we aren’t sure yet what causes the excess accumulation of porphyrins in springhare fur.” (History nerds might remember that porphyria, often caused by a genetic mutation, plagued many European royal families.)

A growing body of research also indicates that nocturnal mammals can see ultraviolet light, raising the possibility that these species can see in ways that we can’t, unless we have a special flashlight.

But it’s also possible that mammalian biofluorescence is an evolutionary coincidence, without any biological or ecological role.

As with any new discovery, the key will be more research. Olson, Reinhold, and many other scientists are hard at work unpacking the mysteries of glowing mammals: which species fluoresce, the biochemistry behind their color, and the potential role of florescence in species ecology and behavior.

“We can hope and speculate that there’s more to it, but at this stage, who knows?” says Reinhold. “There’s a lot more about how animals use light and see their environment that we just don’t have a handle on yet.”

Until then, pack a UV light with you the next time you go exploring at night. You never know what you might find.

Marsupials are a type of mammal, placental mammals. Which isn’t clearly stated in your work, it can also lead to confusion as most people think of Opossums as marsupials. Which is not explained. Although Marsupials are in the Mammalia family they are not commonly known as mammals. As their live young are kept in a pouch, unlike dogs or cats.

Im very disappointed in this article. Calling yourself a science writer but then lable 2 marsupials as mammles. Opossums and Sugar gliders are Marsupails. This is basic.

Cordelia,

Thank you for your comment but you are incorrect. Marsupials are mammals.

Where are these animals located?

A great introduction to another amazing feature in nature. I have been amazed for years by the UV lights showing scorpions at night as well as some species of millipedes. I am sure there are numerous other glowing arthropods that glow under UV. I have yet to find a conclusive explanation of how and why scorpions glow in the dark. If you know of a good resource for this information, I would appreciate it. Thanks again for the great articles you publish.

This is so fascinating! I’m already looking forward to doing some exploring with a UV light. I’d read an article about plants with these traits, but didn’t realize some creatures do this, too. What an amazing world!