I glanced out the window on a cold, gray February day, and saw a little greenish form hovering by our shed. It flew in rapid flight, then hovered again. Unmistakable. A hummingbird.

Wait. Could it be? A hummingbird, in Idaho, in February?

Just like that, it darted off. But a few days later, it was back, and this time my wife Jennifer was there to witness it as well. Our initial reaction was to pity the poor wayward creature, obviously spending the winter way too far north. In the ensuing weeks, I’d keep seeing the little bird, which I had identified as an Anna’s hummingbird.

And a little research revealed that we needn’t worry. Anna’s hummingbirds, it turns out, have increasingly shown up in Boise in recent years. The Intermountain Bird Observatory was keeping tabs on them, and was receiving reports of up to 60 spending the winter here each year.

The surprising hummingbird also marked a milestone of sorts. It was the 50th bird species for my backyard bird list I started during the pandemic quarantine.

Wherever you live, there is interesting bird activity nearby. And there’s perhaps no better way to discover those birds than by keeping a yard list.

A List Made for Non-Listers

I’ve enjoyed seeing, identifying and observing birds for as long as I can remember. I also have resisted keeping a list of my sightings. Hard-core birding, with a focus on numbers and spreadsheets, held little appeal. I have read the books about big years – the individual efforts to see the highest number of bird species in a year – and most frankly leave me feeling weary. I can admire the obsession but ultimately it seems like trying to see how fast you can enjoy nature. Which kind of defeats the purpose.

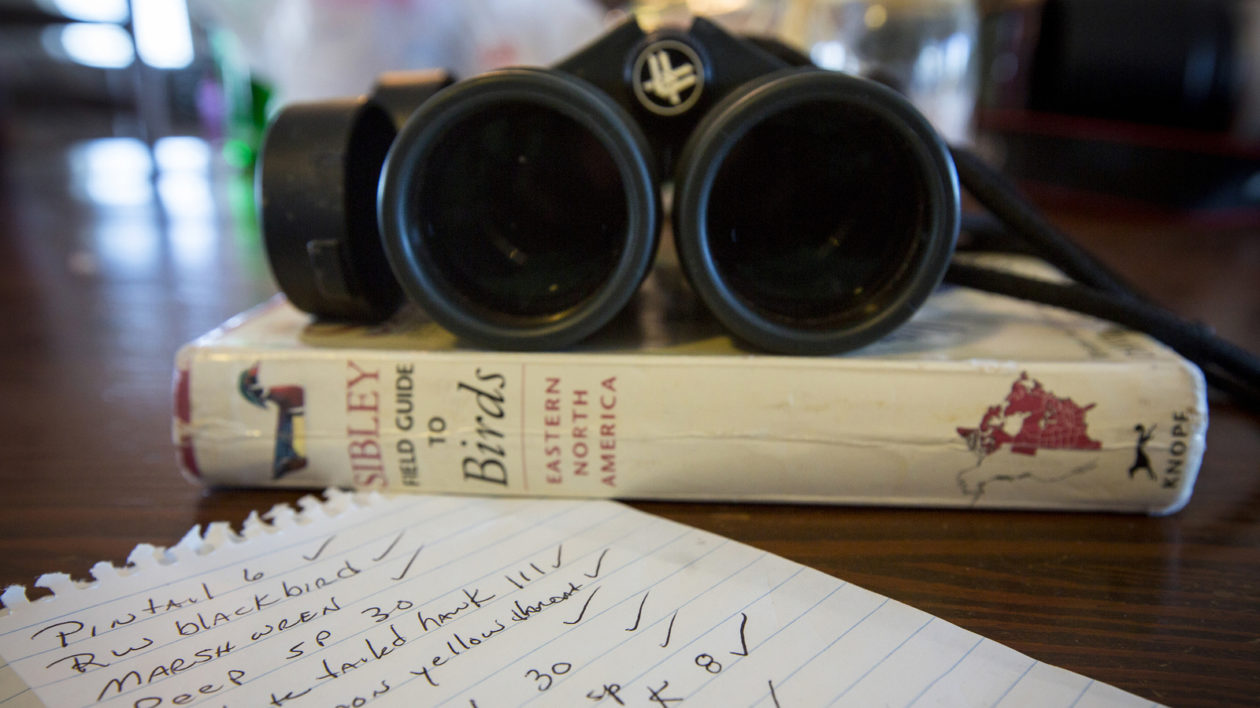

A year ago, my colleague Justine Hausheer wrote a post celebrating the “yard list,” a list of the birds you’ve seen in (or from) your yard or another local spot. She described it as “birding for people who hate lists” and made specific reference to my own ambivalent feelings towards competitive birding.

Being the start of quarantine, I was working from home. As a keen naturalist, I’ve always kept tabs on the local wildlife. Tracking what birds I saw would be an extension of that, without the trappings of hard-core listing. So I started keeping a list.

Living in the arid western United States, I knew my list potential was somewhat lower than many parts of the world. But I looked forward to finding what I could. I consider myself a skilled wildlife observer, but I was surprised when I started noticing species I hadn’t before.

Part of this was simply because I was home during the workweek rather spending those hours in a windowless office. But there’s also this element, true for any form of wildlife observation: you see more when you’re looking with a purpose. I had no competitive aspirations (although Justine and I do keep regular tabs on our yard list tallies). Just having a reason to look means you look more.

I noted one species I had never seen before, a western wood-pewee, a little flycatcher that would roost on a pole in our backyard, then dart out to catch fluttering insects. I find myself wondering if this was truly a new sighting or the pewee had just escaped my notice before I started a yard list.

Some birds that I considered unusual sightings – ruby-crowned kinglet, red-breasted nuthatch – I now see regularly. I just needed to pay more careful attention to what’s fluttering around the tree branches. I was surprised to note a house wren, a familiar bird that was unfamiliar to my backyard.

When I step outside to play with my son or tend our chicken flock, I turn my gaze skyward and am sometimes rewarded with new birds. It could be migrants like a flock of tundra swans, or a bird flying to the Boise River for an evening roost, like a bald eagle or great blue heron.

Such abundance, all around me. It doesn’t require much to enjoy. I have seen each of the 50 birds on my yard list without aid of binoculars. You can see similar marvels, wherever you are. In a city park or greenbelt path, a vacant lot or wastewater pond: there are birds waiting. All you need to do is look.

The Value of Observation

It turns out that the Anna’s hummingbird I saw is indicative of a trend. Prior to 1930, this species only bred in Baja California and southern California. It is one of those species that has benefited from human alterations to habitat. As people planted more flowering trees, the birds expanded rapidly north up the Pacific Coast.

The first record of one in Idaho was in 1976. Now up to 60 a year are recorded. The Intermountain Bird Observatory is banding these birds and trying to learn more about them. Despite our sometimes harsh winters, researchers are finding that the birds have plenty of body fat. But to learn more, the observatory needs people to record sightings (and I did).

Many bird population trends have been tracked by backyard birders through large efforts like the Great Backyard Bird Count and Project FeederWatch. There are also other research efforts that ask birders to report specific species sightings. While one sighting is an anecdote, when taken with thousands or millions of sightings, researchers can gain insight into bird conservation.

The spread of non-native Eurasian collared doves is one trend clearly documented by backyard birders. We’ve lived in our current home for 16 years and I can remember when we first noted a collared dove. (Oddly, I was able to catch it by hand). Now, these birds nest in our neighborhood in fairly large numbers. Birders across North America have noted the same change.

Some species, like Carolina wrens, have expanded north – abetted by climate change, no doubt, but also because human habitats provide suitable food and shelter.

So you can enjoy nature, close to home, and contribute to conservation. When you get right down to it, birding really is the perfect nature activity.

The Wonders of Birding

I make that claim with a little trepidation. I have been obsessed with cool and bizarre mammals since childhood, and have spent no little amount of time, money, and effort to see furred creatures. My love for freshwater fish grows every year. I am a reluctant birder, but I’m forced to admit this: as a hobby, birding is tough to beat.

Many avid naturalists like to discuss what is the “next birding.” I’ve written stories on this very topic. But the fact is that many nature activities are best when you travel or have specialized equipment or significant field experience. Take mammals. Mammals are undeniably charismatic and often memorable.

But seeing a long list of mammals requires travel, often expensive travel. Even then, many mammals are small, cryptic, hard to identify and/or nocturnal. If you’re reading this, I probably don’t need to sell you on the wonders of seeing a wild grizzly or an elephant or a platypus. But even if you love wildlife, spending time looking for and identifying small rodents or bats is, well, an acquired taste. This is even more true with reptiles, fish, moths, dragonflies or wildflowers. All have their afficionados, and I have spent many enjoyable hours searching for all of them. But to get the most out of herping or mothing, you need a degree of patience. There’s a learning curve. You have to develop field skills.

But birds? Birds are here. Flitting around a fountain, a feeder, that scrubby patch of land you pass on the way to the supermarket. While there are certainly identification challenges, many species are active during the day. They are beautiful and they fill the spring air with their songs. With the variety of apps and field guides available, you can start watching them today and likely have success.

Birding goes well with other outdoor activities. Whether on casting on a trout stream, waiting on a deer stand, or plodding along a hiking trail, you can see new birds. Sometimes I wonder how my outdoorsy friends who don’t watch birds pass the time when the fish aren’t biting or the hiking trail grows long. I realize I’m always looking, because there’s always a good chance to see an interesting bird.

In fact, while pacing around thinking of this story, I saw seven species out my window. There’s no need for spendy trips (although, of course, you can see birds on trips near and far).

It’s the perfect reminder that nature is not something “out there,” or that conservation is just about protecting wilderness and so-called “pristine” areas. Birds live with us. They need our attention. And one of the easiest ways to help them is to observe them.

Go on and take a look. And let me know what you find.

I keep Sinkeys on my kitchen table alo g with binoculars. We have feeders and a fish pond with a waterfall. So many birds come for food and wat

e all winter. A heron ate most of the fish but now the pond is inhabitat by a pair of mallards. Saw the first red breastfed nut hatch at the feeder. Morning g doves live in the big spruce and eat the seeds that fall on the ground.

So pleasurable watching all of them.

I live in SC.It has been two years since I last saw nuthatches.Two arrived approx.two months ago.ialso now have a pair of gold finches.my usual purple finches remained during the winter as did my 2pair of cardinals.Nomorning doves as yet they are my usual feeder birds.Sparrows and 2red belly woodpeckers.i have ten nesting birds right now.

I now have 20 years of bird records in my smallish (1/3 acre) suburban yard! It’s interesting to see the trends throughout the seasons and through the years. I participate in FeederWatch, GBBC, and eBird, but I find my own records increase my enjoyment of my habitat garden immensely. I have posted them on my website at https://ourhabitatgarden.org/home/creatures/birds/our-birds/.

“Looking with a purpose” is referred to as ‘delibity’ deliberate serendipity by Kevin J Cook, naturalist based in Loveland, CO

Great article on the ease and joys of birding anywhere you are, any time you step outside. The one on the hibernating/ waking black bears is also great, especially since we here in eastern Los Angeles just had a black bear strolling one of our neighborhoods, Eagle Rock, at prime time, around 7pm on March 2. https://patch.com/california/los-angeles/bear-rambles-through-eagle-rock-miles-forest

This after the famous cougar P-22 took an early morning (4am) stroll the day before, caught on a Ring video in the Los Feliz neighborhood of LA. If i could attach the video here for you and your readers, i would. Thanks so much for your fine writing and for sharing with us your love and experience of all elements of nature!

I’ve kept a yard bird list for the 20+ years we’ve lived at our residence in the Arizona mountains (we have a number of similar Western mountain bird species in common with you), and have seen 73 species total, including just this past year a Great Blue Heron checking out our very small backyard pond for about 30 seconds before it realized no fish were present; and a peregrine falcon flying over the house (hey, airspace above the house counts, right?). I’ve seen two “lifers” from yard-birding (N. Pygmy Owl and Calliope Hummingbird). Nestboxes, water features, landscaping, feeding…all of help attract even more species. And, watching our most common birds to get deeper observations in their daily behavior is such a treat. Thank you for a great article!

Thank you for a peek into the bigger birding world, which we see little of because we’re tucked way up into the east side of the North Cascades. Our Juncos just arrived yesterday 3/3/21 to join our year round Chickadees, Nuthatches, Woodpeckers, Steller Jays, Clark’s Nutcrackers, Ravens, and Owls.