Our shoes stir small puffs of dust on the still August morning. It’s that point in the hike when the words flicker out, when the only sound is my quick-dry shirt scratching against sagebrush. I stop to remove a grass seed lodged in my sock, when fellow hiker Tess O’Sullivan points ahead. “How about we stop for lunch?”

A grove of aspen trees shimmers in the light breeze, standing out in Idaho’s Pioneer Mountains. We stroll into the shade, a seemingly secret refuge in the high desert surroundings. Only it’s not a secret, as the trees themselves attest.

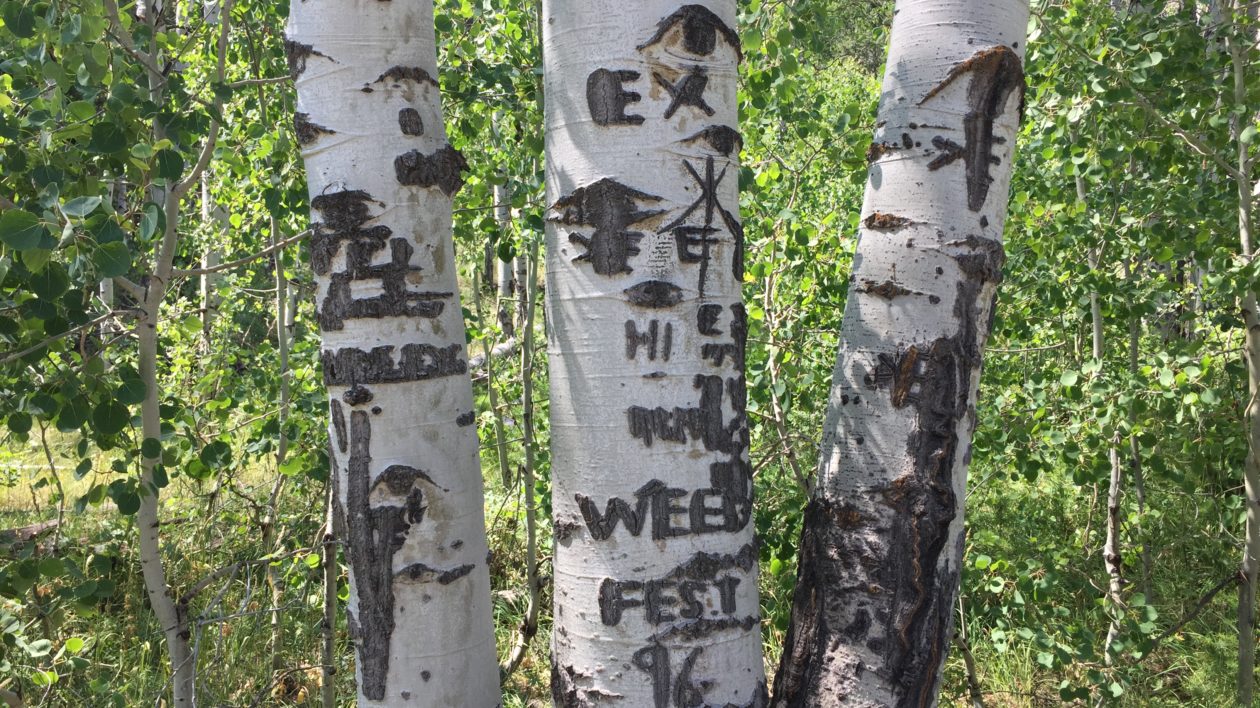

Generations of seasonal Basque and then Peruvian sheep herders have carved the white aspen bark, leaving a record of their own lunch breaks. Some of the carvings have warped with time, leaving them barely legible. Others clearly spell out dates, the names of beloved hometowns and family members, snippets of love songs, rough sketches of wild animals.

The animals may represent creatures they saw right at this spot. As we sit down, three dusky grouse flush out from a patch of brush. A pine squirrel scolds us overhead, as chickadees flit from branch to branch. Elk droppings are scattered in moist seeps throughout the little grove.

It’s not difficult to see the appeal of an aspen grove in the high desert, whether you’re a human or an elk. But this little patch is more than a desert oasis. The often-subtle variations in the landscape – called microhabitats — may hold an important key in helping thousands of wildlife species adapt to climate change.

The Pioneer Mountains, at first glance, might seem to have little variation. “If you’re driving through this area at 65 miles an hour, it just looks like brown hills,” says O’Sullivan, a conservation manager for the Conservancy’s Idaho Chapter. “But when you start walking around, these little microhabitats start to show themselves. They are what are so important to wildlife.”

A decade-long effort by 150 scientists has mapped microhabitats like this across the United States, using such data to identify the most resilient landscapes in the face of climate change. If properly protected, these lands could provide a network of safe havens – allowing species to better adapt to the threats of climate change.

What Makes a Landscape Resilient to Climate Change?

It’s no secret that the world is in the midst of an extinction crisis, facing the largest loss of animal and plant species in human history. An estimated one million species face extinction in the coming years, mainly due to habitat loss.

Many species are also on the move to escape the effects of climate change. In North America, species are shifting their ranges an average of 11 miles north and 36 feet in elevation each decade. Many species are approaching – or have already reached – the limit of where they can go to find hospitable climates.

That’s why conservation scientists seek ways to protect lands most resilient in the face of climate change. It’s the focus of the Conservancy’s effort, with the goal of a connected network of resilient sites that protect the most important habitats in the United States.

What makes a landscape resilient? Mark Anderson, the lead scientist in the Conservancy effort, says he’s looking for certain features. Anderson is known for his love of maps. But he’s quick to note that you can’t think of maps as one-dimensional. “Most of the climate models treat the ground like a flat surface,” he says. “But the climate near the ground can be quite different. The direction a slope faces, low wet basins, little islands of habitat – these all influence the temperature.”

These are microhabitats that offer slight variations in temperature but outsized benefits for wildlife. Even a seemingly specialized creature needs microhabitats. Greater sage-grouse, a species of conservation focus in Idaho’s Pioneers, are well known to need arid sagebrush habitat to survive. But they seek out small springs for water, meadows for foraging grasshoppers and larger brush to nest. Almost imperceptible features of the landscape stitch it together for the grouse.

“A wild animal isn’t perceiving long-term shifts in climate,” says Anderson. “It’s perceiving subtle shifts around it. It moves not because the temperature is increasing every year, but because it needs to move to find food, water and cover.”

But the microhabitats alone aren’t sufficient, Anderson points out. They need to be connected. If different microhabitats are separated from each other by development – whether industrial agriculture, homes, roads or energy sites – they’re essentially off-limits for creatures reaching them.

“We tried to pinpoint unfragmented areas where species could move along the climate gradient,” says Anderson.

Finally, the dataset identifies areas already recognized for biodiversity, relying on long-time Conservancy science.

Mapping these factors – microhabitats, connectivity, biodiversity – allows conservationists to hone in on the places where conservation investment can make the biggest difference in the face of climate change.

Anderson acknowledges he spends a lot of time poring over maps to identify places on a nationwide scale. But he also notes that this is not an arcane exercise. Anyone can detect these microhabitats, even if they’re just out for a hike.

“If you walk in a place like the Pioneers, you notice the places that offer shade,” he says. “You can see pretty easily see where the slopes are steeper. Even on a short walk, it becomes pretty apparent.”

Gravitating Towards Refuge

It’s certainly apparent to O’Sullivan. She’s spent the past 15 years traipsing around the Pioneers, beginning as a land steward for a conservation-minded sheep ranch. She knows the slopes where snow melts more slowly, the little springs, the aspen groves, even the large boulders that provide bits of shade.

“You learn where these spots are by spending time out here,” she says. “You might even say you gravitate towards them. Just like we did when we were looking for a lunch spot.”

We had began our day by driving through Craters of the Moon National Monument, an area shaped by thousands of years of lava flows. The view indeed looks like a moonscape: rocky and inhospitable. As we turn onto gravel road, the land shifts to sagebrush, and as we climb, small patches of conifers and aspens appear.

The Pioneers, a 2.6 million-acre landscape, is a place where you can see strutting sage grouse but also have the chance of encountering a wolverine. As we hike through the desert, we round a bend in the trail and come face-to-face with a beaver dam. I glance into the pond and see the rises of native redband trout. I suspect most tourists would give you strange looks if you told them that this landscape held beavers and trout.

But even the most casual lava photographer understands another facet of this place: It’s vast. The kind of place where you don’t want a flat tire. Towns are few and far between.

O’Sullivan points out a small herd of pronghorns grazing. If the Pioneers had a mascot, this Pleistocene mammal would be it. Pronghorns are fast, capable of speeds approaching 65 miles per hour. But most notable here is not how fast they roam, but how far.

Pronghorns studies here reveal the animals can move 100 miles in the fall and spring, one of the longest large mammal migrations on the continent. And, with the exception of a few road crossings, they can make that migration essentially unimpeded by development.

That’s in no small part due to extensive public land. But the glue that holds all this together is private ranchlands, often sandwiched in the valleys between mountain ranges. In the early 2000s, the Conservancy recognized the importance of these ranchlands for wide-ranging wildlife and sensitive species like sage grouse. They worked with partners and willing landowners to protect these ranchlands from development, to date protecting more than 95,000 acres.

“This landscape has been a priority for land protection for a while now,” says O’Sullivan. “It has now emerged as a priority for climate resilience too. For a land conservationist, mapping resilience shows us where to prioritize. This isn’t just about protecting land that is important to wildlife now, it’s helping us to protect land that is going to be important for the future.”

The effort to identify resilient lands will help conservationists make these decisions across the United States. Both O’Sullivan and Anderson note that this isn’t a silver bullet: there are many factors at play in conservation. But connecting a series of microhabitats may offer one of the best chances we have at protecting thousands of species.

Sitting in a grove of aspens, the leaves shimmering in the breeze as I read carvings on trees, I can enjoy this brief respite from the desert heat. By itself, it is a nice spot but hardly seems like something that could save the planet’s biodiversity. But stepping back, looking at the data, one can imagine this piece connected to others like it, like a quilt that incorporates everything from soil to wolverines, sage grouse to beaver dams. A quilt that stitches together groundbreaking science, decades of land conservation success and hope.

And yet, Idaho’s most draconian of all exploitative wildlife policies remain intent upon completely extirpating the native Gray Wolf from every habitat, having created an 11 month hunting season, allowing trapping and digging out to kill blind altricial pups. All without need, as demonstration nonlethal methods have shown predation on domestic sheep and cattle is negligible, predator populations after initial rise ALWAYS fall back to low densities.

Consider well that this essential native predator has never risen in population in any state yet beyond that of a single tiny incorporated human town.

Further, the wolf has been incontrovertibly shown to be protective of the present thin pronghorn populations, through its reduction of dense coyote populations. Coyotes are able to target pronghorn fauns ( or kids) during their most vulnerable time imediately following birth. Wolves are not, and should the wolf be allowed to return in normal ecologically effective numbers, pronghorns could return toward their once-estimated 30 million or possibly double that population, extant into the 1870s in the North American west.