At first, Brittney Cade wondered what she had gotten herself into: Plant trees in one of the driest regions of North America? How’s that going to work?

Cade had just begun as an AmeriCorps stewardship assistant for The Nature Conservancy in Nevada. She would be based in Beatty, Nevada, adjacent to the legendarily hot and dry Death Valley National Park. Her first task would be to lead an effort to plant riparian trees. Thirty thousand of them.

“The desert was completely unfamiliar to me,” Cade says. “I come from the South Side of Chicago, the urban Midwest. I did not associate trees and water with the desert.”

When she arrived in Beatty, she encountered the Amargosa River, the site of her project. This was not the Mississippi. There was no expansive floodplain, no raging torrent. In spots, you could jump across it. But she soon recognized the Amargosa’s outsized importance in the Mojave.

“This river, it’s life,” she says. “It’s importance to biodiversity is so apparent. My main goal was to get field experience, and I soon saw what I could learn here.”

Cade worked with volunteers to get 30,000 trees planted this fall, part of an overall 100,000 tree goal over the next three years. It is part of an effort to help the Mojave Desert’s beleaguered birds adapt to climate change. And it builds on a decades-long conservation legacy in the Amargosa.

“It’s inspiring seeing this habitat come to life,” says Cade. “We aren’t planting trees for the aesthetics. It’s much bigger than that.”

Silent Desert: The Mojave’s Bird Decline

A paper published in 2019 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences documented a collapse of bird populations in the Mojave Desert over the past century. The research found the culprit to be hotter, drier conditions brought on by climate change – and it’s likely to get worse. Another threat not addressed in the paper, groundwater pumping, also drives surface water decline. With riparian habitat shrinking, many birds faced extreme stress. As the paper noted, “Birds with the greatest water requirements for cooling their body temperature experienced the largest declines.”

As a recent story I wrote for Nature Conservancy Magazine noted, species across North America are adapting to climate change by shifting their range northward and to higher elevations. Birds can make this shift relatively easily in, say, along the freestone rivers and expansive forests of the Rocky Mountains. But in the harsh, dry desert, every bit of habitat counts.

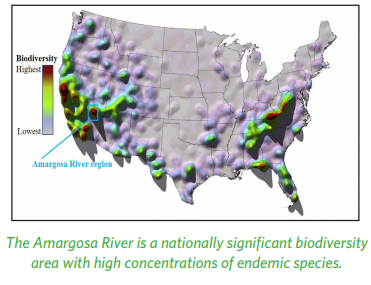

The Amargosa River winds for 125 miles through the Mojave, terminating at a popular tourist spot (and the lowest-elevation spot in North America) called Badwater Basin in Death Valley National Park. While there can be spring flows, over much of its length the Amargosa flows beneath the surface. And while it may be a small river, it is home to endemic species and is vitally important for breeding desert birds. More than 250 species use the river’s corridor as breeding, nesting and migratory habitat.

“There are birds that nest along the southern and middle stretches of the Amargosa River that don’t nest in the northern end of the river,” says Leonard Warren, Amargosa River project manager for The Nature Conservancy. “This makes the northern end a great place to restore habitat and monitor potential bird range shift.”

“There are birds that nest along the southern and middle stretches of the Amargosa River that don’t nest in the northern end of the river,” says Leonard Warren, Amargosa River project manager for The Nature Conservancy. “This makes the northern end a great place to restore habitat and monitor potential bird range shift.”

Some birds are already showing up in the northern part of the river. Ash Meadows National Wildlife Refuge, forty miles south of Beatty, was once the northernmost breeding range of the verdin. But verdins are starting to nest around Beatty, with two nests reported in 2019 and five in 2020.

“This doesn’t mean it’s a climate-induced range shift,” says Warren. “That can be difficult to determine. Our job is to provide the best suitable habitat for the habitat for the birds. The rest is up to the birds.”

Other bird species like the black-tailed gnatcatcher, crissal thrasher and Lucy’s warbler also have their northernmost nesting range just to the south of Beatty. But if they expand north, will they find suitable habitat?

In recent years, the river along Beatty has lost a great deal of the dense riparian habitat used by birds – but it’s for a good reason. That vegetation was the invasive (and water sucking) tamarisk.

“They did a great job of removing the tamarisk but that doesn’t leave much left for the birds,” says Warren. “The good news is that left a clean slate for us to conduct habitat restoration.”

Screwbean mesquite, a native tree, has suffered a mysterious die-off along southern parts of the Amargosa, further amplifying the need to restore habitat.

This need launched the project to plan 100,000 trees over three years along the Amargosa. It has been supported by a Climate Adaptation Fund grant from the Wildlife Conservation Society. The North Arizona University Foundation has helped plan the project, collect cuttings, gather seeds and grow the appropriate seeds.

Warren notes it was important that the trees were self-sufficient from the start. This meant no supplemental watering once the trees were in the ground. “We only planted trees in moist soil, in areas that received year-round water,” he says. “These are already areas with a lot of birds. We want to increase the density of nesting birds and the diversity of species.”

A Continuing Legacy

Planting 100,000 trees – and helping birds adapt to climate change – is just the latest chapter in the rich conservation history of the Amargosa. The Nature Conservancy has worked here since the 1970s, including purchasing five properties along the river.

At one point in conservation history, those acquisitions would have been the end point. But on the Amargosa, there has long been the recognition that conservation is never done. Not really. Two visionary Nature Conservancy conservationists, Jim Moore and the late Bill Christian, recognized that there were always new issues to address in this harsh environment. They devoted careers to addressing those issues and involving the local community in doing so.

“Bill Christian and Jim Moore were Amargosa River heroes,” says Warren. “It was their life’s work. Now it’s my work. I want to see these 100,000 trees planted before I retire. And I want to inspire others to continue on, to keep working to protect and restore this special habitat.”

Thirty Thousand Trees

Brittney Cade understands that legacy, too. “When I first came out here, seeing this river was a surprise,” she says. “Seeing how important it was for nature and for people. And now I can help a part of the vision for this river become real. It’s inspiring.”

Cade lives in a bunkhouse on one of the properties the Conservancy owns, the 7J Ranch. The Conservancy’s Conservation Innovation Center on the Ranch is being established to cultivate the next generation of conservation leaders across disciplines, including science, art, community engagement and more.

“I would choose to stay here, where it’s just you and the land,” Cade says, then laughs. “Well, maybe if it had cell service.”

Cade led volunteers from the American Conservation Experience in planting cottonwood, willow and ash trees. As was the case with so much in 2020, the task was complicated by the pandemic. In previous years, volunteer days could draw 20 to 30 individuals to help. Due to COVID restrictions, group sizes had to be restricted to just eight people.

“We had to do a lot of work in a little time,” she says. “But we did it. And I’m looking forward to planting more trees next year.”

Cade will also be building trails, creating interpretive signs and sharing the message of the work here during her time with AmeriCorps. “It has been a passion of mine to inspire people to do something about climate change,” she says. “It sometimes feels like such a huge problem. Well, here is something we are doing. When you see water out here, you realize how much we are all tied to it, both birds and people. We are helping shaping a future for this place, one tree at a time.”

Great work all – hopping we can send some of our Least Bell’s Vireos from the Amargosa Wild and Scenic River up your way!

So interesting and informative. My only complaint is that I do not get “Cool Green Science” very often.