Ecologist Jim Moore points to tadpoles swimming around in puddles. A few feet away, water trickles by through bare earth adorned only with some freshly-planted shrubs. We’re within sight of a convenience store/ice cream parlor/souvenir shop parking lot.

This is what a major conservation victory looks likes.

Just a few years ago, the outcome before us would have seemed wildly unlikely.

Today, the water is flowing through a restored river channel in the town of Beatty, Nevada, creating wildlife habitat, flood control and recreational opportunities.

It’s the latest milestone in the conservation of the Amargosa River – a Mojave Desert waterway that provides a vital refuge for plants and animals, some found nowhere else on earth.

The Nature Conservancy has been working since the 1970s to protect the Amargosa. For the past three days, I’ve been visiting project sites throughout the river’s course in California and Nevada, learning about significant challenges, but more importantly seeing notable conservation successes.

It’s a project that typifies what the Conservancy does best. Two field conservation leaders are working with local communities and partners, using the best science available, to shape a hopeful future for that most precious of resources – water in the desert.

A Ribbon in the Desert

But first, let’s define what we mean by “desert river.”

When you imagine a river, you might picture a significantly-sized waterway, one that might require a boat or at least a pair of hip waders to cross.

In many places I’ve visited, I can easily cross the Amargosa River in one step, without breaking stride. It feels more like a tiny stream, the kind of place where I’d flip over rocks looking for crayfish as a kid.

But even small water packs a big ecological impact in the desert. The river creates a ribbon of green in the Mojave, one of the hottest, driest places on the planet.

Cottonwoods and other riparian vegetation line the banks in many places, evidence of brief but intense spring floods and water flowing below ground year-round. In other areas, reeds wave in the breeze.

A variety of bird song fills the air. But most notably, this watery habitat provides habitat for species found nowhere else on earth – desert fish, a toad, snails, a vole.

This narrow channel winds for 125 miles – mostly dry at the surface along the way — until it disappears in Death Valley National Park, at the popular tourist spot known as Badwater Basin.

The story of desert rivers is often one in which wildlife and ecology lose out to the demands of agriculture, subdivision and energy development.

Why is the Amargosa still flowing, with much of the high-quality habitat protected along its course?

That’s what I’m here to find out.

Building a Desert Conservation Legacy

I first met Bill Christian, the Conservancy’s Amargosa River project director, two years ago while working on a story about energy development in the western Mojave. Within five minutes of our introduction, Christian invited me to visit the Amargosa – and he’s been inviting me ever since.

He bubbles with a youthful enthusiasm for the river, apparent in every conversation. “I breathe a sigh of relief when I get along the river,” he says. “Even though I know there are challenges, I see the plants and birds and fish here, and I feel good.”

And for good reason. The Conservancy has been working here since the 1970s, when it purchased a desert spring in Ash Meadows that was originally slated for a huge housing development. (Read more about that project, and the unique fish found there, in last week’s blog).

Through the decades, the Conservancy has protected more than 18,000 acres through acquisition and easements. Approximately 3,600 acres of these lands were acquired by the Conservancy and turned over to the Bureau of Land Management with special deed restrictions, ensuring that their conservation value is preserved in perpetuity.

The acquisitions targeted areas with the best habitat or the best opportunities for restoration, including removal of invasive species.

By 2012, the majority of the high-quality, riparian and spring-fed habitats along the Amargosa River in California were in public ownership, being managed by the BLM for biodiversity.

I also visited one of the protected areas in private ownership, a date farm known as China Ranch. This property had a conservation easement, a legal agreement protecting a spring that feeds the Amargosa River while also allowing the date farm to continue operations.

The China Ranch’s visitors can stroll around the date trees, have a date milkshake and stay in cozy teepees.

They can also learn a bit about the unique ecology there: a nature trail winds along the spring, pointing out where to see the endemic Amargosa speckled dace, a small fish species, and other interesting species.

It’s a striking example of how a community business can both protect and benefit from the desert river.

But not everything about the Amargosa River is so rosy. Christian points out the two very different legal systems regulating groundwater pumping in California and Nevada, making it difficult to compatibly protect wildlife through water law in a project that spans both states.

There’s widespread over-allocation of water resources. He points out the alfalfa farms that provide dairy farms in the area, an intensive use of water. “Dairy in the Mojave Desert is a terrible idea,” he says.

And there are new residential housing developments, and solar farms with their own considerable water demands.

“We have a great legacy of protection here,” he says. “But the nature of what we do means that there are always new issues.”

But here the real benefit of conservationists working in a place for decades, for the long haul, becomes apparent.

Staff have built relationships with communities, with individuals, with government agencies. There’s been a local land trust, the Amargosa Conservancy, established. Christian finds people more willing to support conservation.

“I love the people here,” he says. “This is not an easy area to live, out here in the Mojave Desert. Just as the wildlife is unique, so are the people. For conservationists to be successful, you need the science. But you also need to learn the area, to listen to people, to establish trust. That’s what has enabled us to be successful here. It’s what we will need as we work to protect the Amargosa from new threats.”

From Suspicion to Support

A similar story of community-building has developed in Nevada; the recent river restoration stands in testament to its effectiveness.

Beatty, Nevada may be the nearest community to Death Valley National Park, but it still seems only nominally a tourist town. Sure, you can easily find a great home-cooked meal in the downtown, and stay at a comfortable hotel.

But it’s also the kind of place where a Wyatt Earp look-alike comes strolling by your table, with a manure-splattered duster and jangling spurs. The kind of place where a sign promoting a t-shirt shop is followed by a billboard advertising a brothel.

Unsurprisingly, this is also the kind of town that typically views the activities of environmentalists and the federal government with suspicion. This is exactly the environment Jim Moore, Mojave ecoregional ecologist for the Conservancy, found when he started working there in 1992.

“They thought the reason we were there was to take away their lands and turn it into another wildlife refuge,” says Moore. “It was a volatile time. We had to overcome a lot of suspicion and anti-environmental sentiment.”

The Amargosa River flows right through Beatty, but when Moore started working there it was hardly the desert jewel I had seen in other places. A fear of flooding meant a channelized, unnatural river.

“People wanted to get the river through town as quickly as possible,” he says.

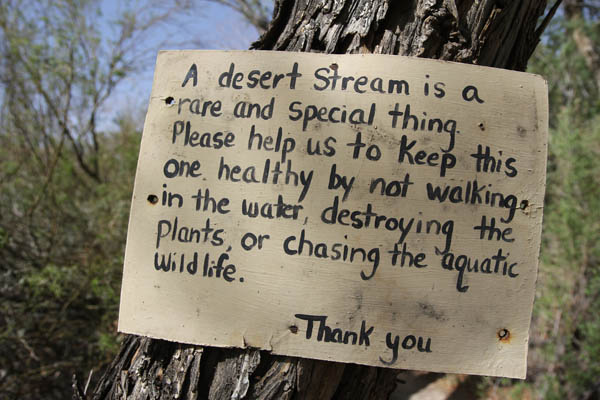

In 1994, there was a decision to list the Amargosa toad – an endemic species – as an endangered species along a 12-mile stretch of the river. “We told the community that if we did this right, we could avoid a federal listing,” says Moore. “We could do everything a listing would accomplish for the toad, but with a Beatty spin.”

Moore attended the town meetings, ate in the local restaurants, listened. Over time, slowly at first, things started to change.

Landowners signed conservation agreements. An Amargosa Toad Working Group – comprised of landowners, university researchers and agency staff – developed conservation plans. The Conservancy acquired properties and worked with other landowners (including the local brothel) that had toads on their lands.

But there was still that stretch of river through town. A berm installed for flood control in 1970 completely altered the river’s hydrology and ecology, and not for the better.

A straight river channel ran through thick, weedy vegetation. It was avoided by toads — creatures that need disturbance from floods or other natural forces to survive, and that don’t do well in thick, choked habitat.

And it was avoided by people. The Amargosa was covered in litter and trash. It was impossible to walk there.

Could it be something more?

In 2008, a local business owner agreed to donate his river property for restoration. The berm was removed. Willows and cottonwoods were planted along its banks.

The stream channel was reconfigured so that it had room to meander. The water had just been allowed to flow in this new channel two days before my arrival. Already Oasis Valley speckled dace were appearing and Amargosa toads had laid eggs. Their tadpoles were emerging in shallow pools.

The river could now be a dynamic and functioning natural system.

And more: part of the restoration was installing a passive trail system, an asset for both locals and tourists.

“Tourism is really the only viable enterprise here,” says Moore. “A lot of tourists visit here when coming to or from Death Valley. This will be a nice contrast. They can enjoy a nice walk among trees, toads, fish and babbling brooks.”

Now the river will be a community highlight rather than just a means to get water out of town.

“When we designed this restoration, we wanted to slow the river down, spread it out, soak it in, let it recharge the groundwater,” says Moore. “And that’s actually a great allegory for the human part of the restoration. We want tourists to slow down, soak it in, meander around town. Beatty has a lot to offer them. And it shows that river conservation is not a detriment to the community. It adds to the quality of life for the residents of Beatty and can boost the economy.”

Very meaningful to read this again at a time when Bill Christian has passed. He did so much to ensure a lasting legacy of desert life. Thank you Bill

Great report. Many Idaho rivers in similar straights although most of ours have outlets to the ocean. Many over allocated and I appreciate all that TNC, IRU, TU and others do to help stave off water grabs and educate the public.

As a member of TNC since 1984 and a resident of southern Nevada, I am very proud of the work that Jim Moore and TNC have been doing to inform and educate the community about a unique natural heritage in their town and all the work that has been done for the benefit of the toad.

Jim was recognized for his outstanding work by the US Fish and Wildlife Service, deservedly so, along with other who banded together to make protecting the toad under the Endangered Species Act unnecessary, at least as long as the efforts continue.

Thanks much Rob for your kind words – I’m happy to have worked closely with you on this project and others in Southern Nevada over the years, and your presence out there will be missed.