The first time Wong Siew Te saw the bear, his hairs stood on end and he shivered. It wasn’t a charging grizzly or mother black bear and cub. The sow was walking upright, cradling her baby against her chest in her front legs. She looked like a human mother holding her infant.

It was eerie, Wong says, and amazing.

After more than 20 years studying sun bears, the last dozen running the Bornean Sun Bear Conservation Centre in Sabah, Malaysia, the solitary, tropical creatures still surprise him.

Except unlike the grizzly bear in North America – commonly featured in nature documentaries and fairly easy to see in places like Yellowstone National Park — few people know sun bears exist and even fewer care about their plight.

They’re the least studied bears on the planet and also heavily poached for their paws (considered a delicacy in some countries), their gall bladders (said to have healing properties), their canines and claws (which locals believe have supernatural capabilities) and their meat. They also suffer from deforestation of their habitat.

But as research progresses, scientists are discovering increasing similarities with gorillas and humans, including their ability to mimic each other’s facial expressions.

Through a combination of intensive study, harsher penalties for poachers and traffickers and rehabilitation centers, wildlife experts hope to stem the sun bear’s path toward extinction.

Little Bear of the Forest

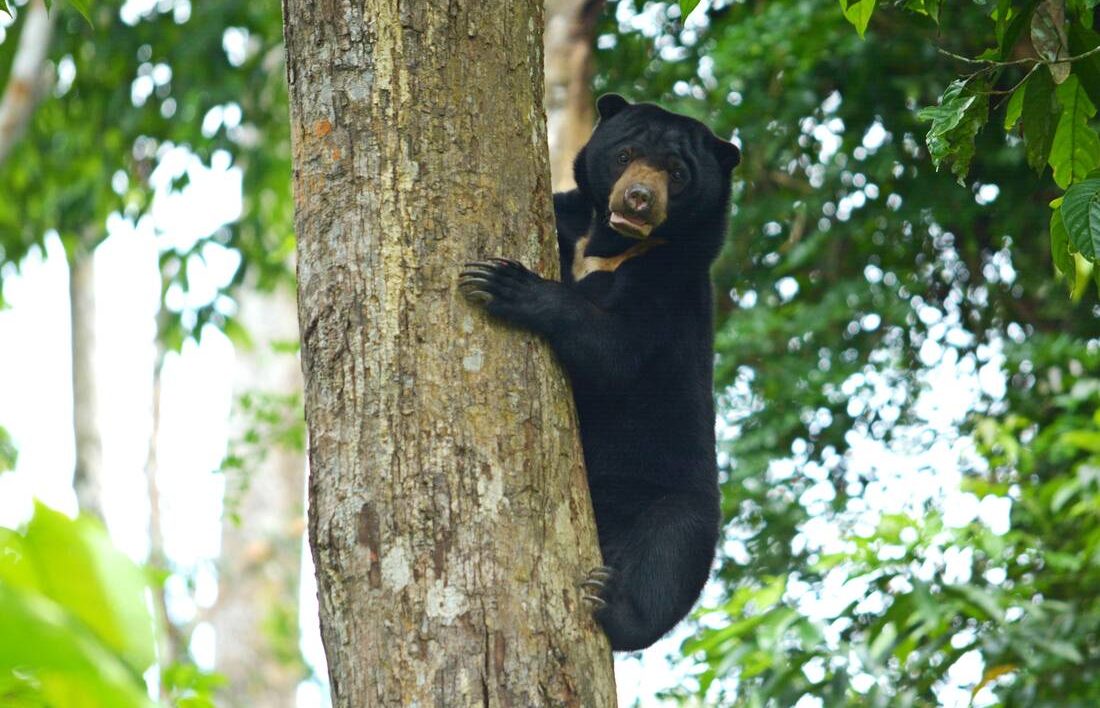

Even at a glance, to the untrained eye a sun bear would likely never be confused for a black or brown bear. They have tiny ears and rounder heads. Their hair is slick and short. And they’re little.

Sun bears are the smallest bear in the world, weighing between 75 and 80 pounds. A big male Borneo sun bear might be 100 pounds. A male grizzly bear, on the other hand, can easily weigh up to 600 pounds (and those that feed on salmon in Alaska can weigh considerably more).

Sun bears live in the tropical forests of southeast Asia and don’t hibernate, spending much of their time climbing, eating and sleeping in trees, sometimes scaling trunks of massive hardwood trees 130 to 160 feet in the air.

That’s why they evolved to be smaller than their North American cousins. A diet of fruits, seeds and bugs will only support so many pounds. It’s also why they play a critical role in the biodiversity of the forest.

They eat fruit then distribute seeds from trees into far flung parts of the forest through their digestive system. They dig for insects and roots helping turn over the soil for other plants.

And when they excavate tree trunks to feed on honey of stingless bees, they leave behind cavities perfect for hornbills and flying squirrels.

They have claws fit for climbing and tongues stretching almost 17 inches used for reaching into holes for honey and termites. Wong has even seen them use tools, cracking coconuts open on rocks to feast on the inside flesh.

“All of this for me is mind blowing,” says Wong.

Facial Expressions

For all their cleverness climbing trees and using tools, the sun bear is a solitary creature. Females stay with their cubs for three or four years and males roam the forests alone. When they encounter one another they often fight, willing to kill to protect their small part of the forest’s resources, Wong says.

That makes recent research out of the Bornean Sun Bear Conservation Centre all the more peculiar.

Sun bears, at least those in captivity, will play and mimic each other’s facial expressions in a way rarely documented outside of dogs and primates.

“I was surprised because the mainstream idea said it wouldn’t be there,” says U.K. researcher Derry Taylor. “But I was also skeptical that you only find complex social behavior in complex species.”

Even Wong, who has as many as 43 bears at his center at a time, was surprised.

The work was part of a project led by Taylor and Marina Davila Ross, also at the University of Portsmouth.

They began by recording hours of footage of the bears playing and interacting with each other. The researchers then combed through the videos noting when each bear made a facial expression and crosschecking those instances with corresponding expressions.

The data showed that when they would play, like nipping another on the back of the neck and then wrestling, the bears would stop briefly, face each other and exchange expressions. Those expressions sometimes included dropping the lower half of their jaw and wrinkling their noses.

“It reminded me of a diver coming up for air,” Taylor says.

The reason behind sharing expressions is left up to educated guesses, but the results were puzzling because understanding facial cues seems to be a trait among more gregarious, social animals. If sun bears live solitary lives, why did they evolve to understand when their buddies want to play?

Mimicking facial expressions was once considered solely a human trait, but that was just because we weren’t looking. Researchers then saw this in apes (our closest relatives) and dogs (which live with us). Taylor wonders how many other species have the same abilities that have simply not been documented.

Protecting What Remains

As researchers discover more about sun bears, the creatures are racing against a fate that feels all but certain to scientists like Shyamala Ratnayeke, an associate professor at Sunway University in Malaysia.

They’re already largely extirpated in the wild from Vietnam and Laos – killed for meat, paws and gall bladders – leaving behind what Wong calls “empty forests.”

The bears are listed as vulnerable on the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and killing them is illegal. But like many other species, that doesn’t prevent poaching.

“The forests need to be patrolled by uniformed personnel and armed personnel to prevent poachers from entering,” Wong says.

Though Ratnayeke acknowledges: “Looking for poachers and snares in the forests is like looking for needles in haystacks.”

Chemists have discovered a synthetic alternative to the healing qualities found in bear bile, but some people still seek the real thing, Ratnayeke says.

Recent studies show sun bears will live in places like cultivated acacia plantations and wander into oil palm plantations for food. And more research helps scientists understand the bears, their range and their specific needs.

Places like the Borneo Sun Bear Conservation Centre also help. Wong leads tours throughout the year to educate children and adults and collects orphan cubs and raises them to survive on their own. He also rehabilitates sun bears found in captivity or kept as pets. He’s released seven bears back into the wild.

Populations in portions of Malaysia remain relatively stable, as far as Wong and others can surmise, through concrete data is lacking.

Understanding the bears better – and understanding their human-like traits – may also help people feel empathy for the creatures and spur a desire to become advocates for the world’s smallest bear.

I have been aware of the demise of yet another innocent creature, the Sun Bear through various environmental and conservation publications, emails and petitions. For those of us who care for ALL the animals, plants, insects, reptiles, etc., we MUST be their voices to live safely and peacefully without anymore intervention from HUMANS! We will prepare to go hoarse if we have to.

It:s good that you’re writing about and photographing sun bears, whose population is declining.

These bears are so Cute! Lol! I Love them! Their Cutie Pies! They need an must be protected! 🙂

Good article. Hope they survive in the wild.

What an amazing beautiful creature. Thank you for educating me on the sun. I want to learn more.

Fascinating article about a fascinating animal. I’d heard of sun bears, but had never really paid them much attention.

I support Sun Bears in my own way. And, you can always count on me to sign petitions, write letters and call my Representatives or Senators if that is doable for Sun Bears. If I can I will donate but, that does not come as easy as the other.

Thank you for all you and your staff do,

Alan

I became aware of the sun bear when I did a children’s program on animals from other lands. The children and parents were glued to the story and pictures. I decided to continue the program as a by- weekly offer ,from there I began an afternoon program for school aged children filling a table with books about all kinds of animals. The program evolved.The children always had a display table full of books about animals they sat with friends and could be heard saying things like did you know”Hey look at this”. This program taught them about the dangers animals face due to population explosion, of human interference, the encroachment of roads, loss of habitat and also the pet trade market.

It was my hope these children would pass on to their children the wonders of the world and the responsibility to include all life.