Thirteen years ago, researchers banded an upland sandpiper on the Konza Prairie Biological Station, a field research station in the Flint Hills of Kansas. Like many banded birds, the bird then disappeared from human notice. Until this summer, that is. A photographer documented it, alive and well, perched on a fence post in the Flint Hills – about a mile from where it was banded in 2006 as a chick on the nest.

At exactly 13 years and 1 month, it is now the oldest upland sandpiper on record. While it was relocated near its banding location, in the thirteen years of existence it likely migrated the equivalent of five times around the globe.

While there are many details of this sandpiper’s life we’ll never know, the details of its finding is in itself a fascinating story.

Bird on a Fence Post

Upland sandpipers are a migratory shorebird species that uses grasslands in North America for nesting and as stopover sites. The Flint Hills, as the last significant expanse of tallgrass prairie, is a vitally important habitat for sandpipers and other grassland birds. In the North American winter, upland sandpipers migrate to Uruguay and northern Argentina, where they also live on grasslands.

Researcher Brett Sandercock spent nine years on the Konza Prairie and four years in Uruguay banding more than 800 upland sandpipers. Banding is a numbers game, with many birds never recorded again. Most bands are recovered when a dead bird is found, or the bird is recaptured by another research crew. But it is possible to photograph birds and record their bands, an activity that has become a specialized niche among birders.

Greg Kramos works for the Partners for Fish and Wildlife in the Flint Hills, a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service program that works with private landowners to keep grassland as grassland. Kramos spends a lot of time looking at prairie habitat and the creatures that live there.

On the first day of summer this year, he had a vacation day. And he spent it on the prairie. “Even my days off turn out to be work related,” Kramos says with a laugh. “I decided to cruise the Flint Hills roads, looking for things to photograph.”

That afternoon, he saw an upland sandpiper on a fence post. “Sandpipers are generally quite cooperative,” he says. “They don’t fly off right away like meadowlarks. I snapped a couple of photos. Then I noticed the bird was banded.”

Sandpipers have thin legs. To fit, a bird band must be similarly tiny. Imagine reading numbers wrapped around a drinking straw at a distance. “I was patient,” says Kramos. “I knew I had to photograph all the numbers. As the bird shifted, I took bursts of photos.”

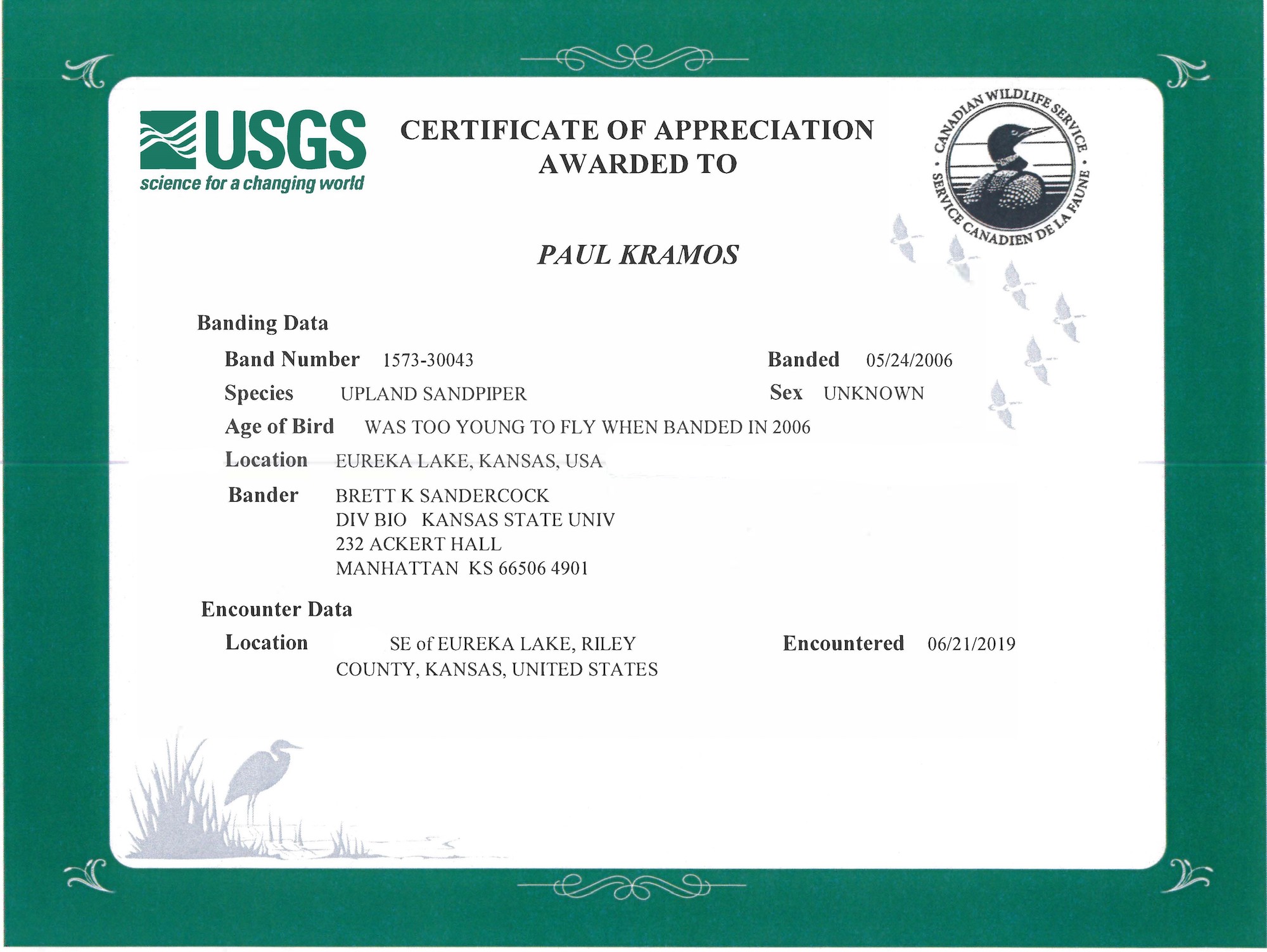

He photographed for 45 minutes, hoping he had captured the band numbers so the bird could be identified. He returned home and filed a banding report with the USGS Bird Banding Lab – and soon began hearing from researchers who wanted to see the photographs. Thanks to Kramos’s attention to detail, and a little luck, biologists confirmed that this was a sandpiper banded as a chick 13 years ago – making it a new longevity record for the species.

“I was delighted to receive this report because I was completely unexpected,” says Sandercock. “Fewer than 1 percent of banded upland sandpipers have been recovered and Greg’s observation almost doubles the previous longevity record of 8 years and 11 months.”

Tracking data show that upland sandpipers in Kansas undertake a round-trip migration of 18,500 miles per year; over the course of the bird’s life, it likely flew the equivalent of five times around the globe. We can only imagine the perils it dodged: bad weather, hunters, pesticides, predators and more.

Despite those long-distance travels, the bird was photographed barely a mile away from where it was first banded at the nest. “They show a remarkable site fidelity,” says Kramos. “They return in close proximity to where they hatched. But finding a bird like this also reveals how much we don’t know about the species. I think we’re just scratching the surface.”

But one thing, Kramos notes, is certain: the importance of prairie habitats for migrating birds.

The Best That Remains

Many conservationists know that grasslands are vitally important as bird habitat. But migratory shorebirds may not be the first species that come to mind.

“When most people think of shorebird habitat, they picture mud flats and the water’s edge,” says Robert Penner, Cheyenne Bottoms and avian program manager for The Nature Conservancy. “But some shorebird species are highly dependent on grasslands like the Flint Hills.”

The Flint Hills is the largest intact tallgrass prairie habitat remaining in the United States.

“At one point, it was the largest ecosystem in the country, and now it’s the most altered in terms of acres lost,” says Brian Obermeyer, director of the Conservancy’s Flint Hills Initiative. “The Flint Hills is the best of what’s left.”

It’s vitally important for many migratory bird species. Many upland sandpipers nest there. Others stop there to rest and refuel before continuing north.

“They’re finding what they need here,” says Obermeyer. “Each year, we get a surge of birds.”

Upland sandpipers are just one of the species that relies on the habitat. American golden-plovers and buff-breasted sandpipers nest in the Arctic but use the Flint Hills as a stopover. In fact, the Flint Hills ecoregion was recently designated a “Landscape of Hemispheric Importance” by the Western Shorebird Reserve Network.

“For migratory shorebirds coming from South America, this is the first big chunk of grassland they encounter,” says Penner. “Birds that are born here will return to within a few miles of where they grew up. If the parents were successful, it makes sense to return.”

They rely on the grassland habitat remaining intact and healthy, and that’s the focus of The Nature Conservancy’s Flint Hills Initiative, a two-decades-old conservation effort to maintain the unfragmented nature of this landscape, and to keep the prairie healthy and free of invasive trees and weeds. To accomplish this, the Conservancy works with ranchers, landowners, and conservation partners including the USFWS Partners for Fish and Wildlife program. One milestone of this effort has been the more than 100,000 acres protected through conservation easements by the Conservancy’s land trust partners.

Besides its emphasis on private lands conservation, the Conservancy has an impressive preserve network in the Flint Hills of Kansas and Oklahoma. The Konza Prairie Biological Station, where the chick was first banded, is primarily owned by the Conservancy and managed by Kansas State University’s Division of Biology. The Conservancy owns most of the 11,000-acre Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve, managed as a unit of the National Park Service. The Joseph H. Williams Tallgrass Prairie Preserve, located in Oklahoma, is the largest protected tract of tallgrass prairie in North America.

“The Conservancy’s focus in the Flint Hills is on protecting what’s here,” says Obermeyer. “Restoration, or converting crop fields back to native plants, is actually low on our list because the Flint Hills still has intact tallgrass prairie. We want to make sure that prairie remains as prairie.”

Migratory shorebirds return year after year, seeking the food and cover that the prairie provides. “We consider this record-breaking sandpiper remarkable, but perhaps 12 years is not that unusual,” says Obermeyer. “we just don’t know. There is a lot about these birds we don’t know. But we do know they need intact, open prairie landscapes. We must protect that, so birds will have something to come back to year after year.”

Thank you!! I adore sandpipers

This story is so uplifting!! With everything going wrong in the world today, this story made me so happy!

Earlier this year I attended an educational program on Hummingbird Banding at the Potlatch Conservation Education Center in Casscoe, Arkansas (know to locals as Cooks Lake). After waiting what seemed like forever for my turn to hold and then release one of the captured ruby-throated hummingbirds, which migrate from North America to Mexico and Central America in winter, I felt doubly blessed to learn that the tiny female had been banded five years earlier. It was an experience I will always treasure.

This is so cool and inspiring. I had just read that piece about the shooting of songbirds in Cypress, Greece and Italy and was torn up by it. What are Human Beings Thinking? This kind of lessons the impact it had on me. The Nature Conservancy Rules.

The Flint Hills are the best! My grandparents’ farm was in that area just outside of Madison, KS.

I love this story!! This is why we support The Nature Conservancy, to preserve important habitat like this for wildlife. For many it’s their last chance. Thank you, TNC!!

Very good article about a neat little bird. Article brought up items I never knew.

Thank you, Greg Kramos, for your patience and photos! And thank you, Matthew Miller/the Nature Conservancy, for bringing this fascinating story to us. I really enjoyed the story and photos!

Living Nature is one of our irreplaceable gifts. If we allow our living creatures to disappear, one by one, we are guilty of ignoring those gifts and allowing this Earth to become less beautiful. Thank goodness for those who devote their time to protecting those irreplaceable gifts.

Wow, this is really cool that this sandpiper has lived this long and comes back to its nesting area. Humans think we know a lot but we really don’t when it comes to other species. That why it’s so important to make it our business to not let any species become extinct. Thanks for an interesting article.

Incrediable! What a story.

This shows that everyone can make a difference.