Casey David thought she knew the Shedd Aquarium’s most charismatic and interesting creatures. She worked in fundraising for the famous Chicago institution, and was well acquainted with the belugas, the sharks, the penguins.

Then one day she met an enthusiastic postdoctoral researcher working in the aquarium’s lab. He casually dismissed penguins as “overhyped,” and informed her that if she wanted to see the really cool stuff, she needed to spend time at the freshwater tanks. And she needed to see gar.

“At the time, I didn’t know what a gar was,” Casey admits.

She met the researcher, Solomon David, for his version of the aquarium tour. They skipped the belugas and looked at all the freshwater oddities: the African lungfish and sturgeon and arapaima. And, yes, they spent a lot of time looking at gar, fish with long snouts, sharp teeth and armor. Fish that swam with the dinosaurs.

“Honestly, I never met anyone as enthusiastic about anything as Solomon was about gar,” says Casey. “I couldn’t help but be swept up by that.”

And so began what is perhaps the first-ever gar-inspired romance. Today, Casey and Solomon are married, with all seven of the world’s gar species swimming in their living room. And Solomon continues to reach new people every year – students, anglers, social media users – with his love of gar and other primitive fish. That “garnado” of enthusiasm remains as strong today.

Gar Trek

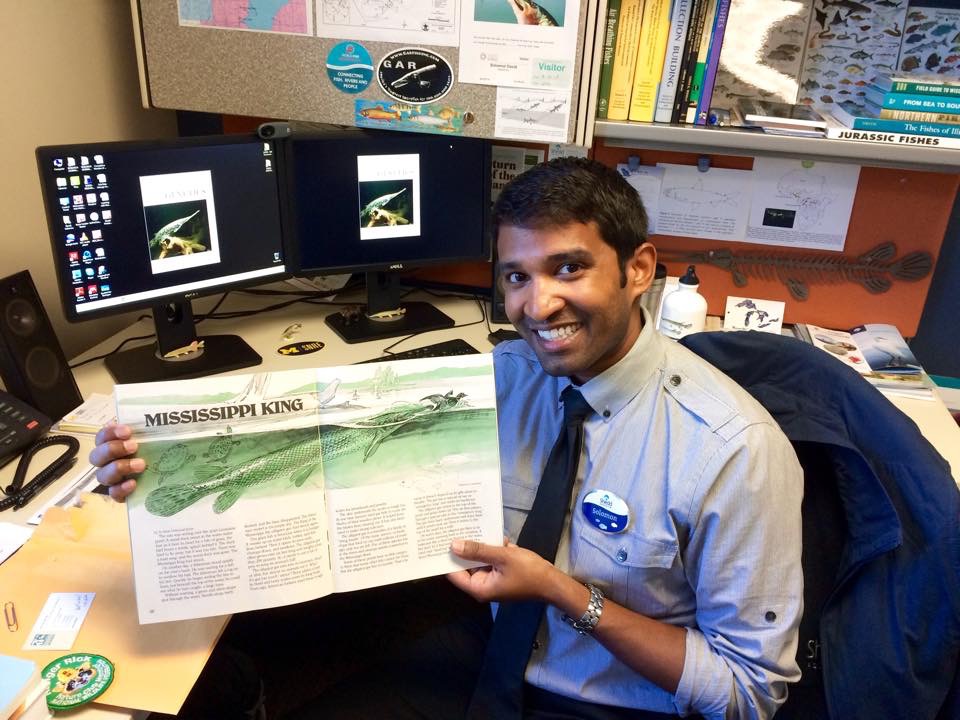

I first “met” Solomon on Twitter, after I had written several articles on illogical angler persecution of native fish deemed to be “trash” – species like suckers and gar. Solomon has a large social media following, and part of his goal was to build appreciation for and debunk myths surrounding gar and other misunderstood native fish. Since reading an article about gar in Ranger Rick magazine as a kid, he had come to be one of the fish’s most vocal defenders. After months of correspondence, we met in person at the Shedd Aquarium.

Soon thereafter we embarked on a trip to see the catch-and-release trophy alligator fishery in Texas firsthand, an adventure detailed in my new book Fishing Through the Apocalypse. I won’t retell that story here but suffice to say that not everything went according to plan, to put it mildly.

On outdoor trips like this, you can tell a lot about a person by how they react when the fish don’t show, when everyone is tired and hungry and dehydrated, and when you have to dig out a badly-stuck truck using only your fingers. I don’t think I saw Solomon grimace once. As long as there were gar – or, at least, the possibility of gar — he remained upbeat and enthusiastic.

Solomon is now an assistant professor at Nicholls State University in Thibodaux, Louisiana, where – among other duties – he runs Gar Lab. He feels right at home in the biology department among faculty like Dr. Allyse Ferrara and Dr. Quenton Fontenot, who not only pioneered research on gar, but were also integral in Solomon’s graduate research on spotted gar.

Solomon’s work has influenced new audiences to take another look at gar. Many anglers, myself included, find them to be fascinating quarry for fly, lure or bait. They bite readily and ferociously. But their tough snouts make them difficult to hook. This adds to the challenge and fun.

Similarly, naturalists find that they are a fish species that you can observe readily via snorkeling or even from shore, as gar often congregate, drifting close to the surface. This gar appreciation has led to conservation efforts and new regulations in states from Illinois to Texas.

That conservation is important to Solomon. But his day-to-day focus with gar is research, in studying what questions this fish can help us answer.

With Gar Lab, the research currently is divided into two different areas. Graduate student Sarah Fontana is looking at the growth and development of spotted gar raised in captivity outside the normal spawning season. Currently, spotted gar are a model organism used in biomedical research. Figuring out how to produce gar in captivity year round has practical applications in raising these animals for research purposes.

His lab’s other project, led by graduate student Anthea Fredrickson, has implications for conservation. This research is looking at spotted gar in two Louisiana watersheds, the Atchafalaya Basin, which receives an annual pulse from the Mississippi River, and the Upper Barataria Estuary, which is now disconnected from the Mississippi and no longer receives a flood pulse.

The research hypothesizes that the lack of an annual flood pulse significantly changes the system’s food web, in particular what predatory fish eat.

“The flood pulse in the Atchafalaya flushed nutrients into the system, and also brings in crayfish and other prey,” says Solomon. “Are spotted gar feeding at a different trophic level because of this? This research gives us a chance to see how human-caused change to ecosystems influences the food web.”

The researchers analyze the spotted gar’s stable isotopes, the chemical signature that can allow them to determine what the gar is eating. “Often, research on fish diet looks at gut contents,” says Solomon. “But a predator like a gar quickly digests the food and often has an empty stomach. So just looking at the stomach may not give the full picture.”

The researchers do compare the stomach contents to their isotope analysis as a way of ground truthing the research. Currently, muscle tissue is analyzed, but Fredrickson’s master’s work also includes investigating a non-lethal method of sampling.

“We are comparing fin clips with muscle tissue to see if they calibrate,” says Solomon. “The goal is to refine a non-lethal method of sampling stable isotopes.”

He’s particularly excited that Fredrickson came up with this aspect of the project, and they both believe this technique could be applied to other gar species.

The work is going to be conducted seasonally across the two ecosystems. “The seasonal variation is important in a system that receives a flood pulse versus one that doesn’t,” says Solomon. “The prey can vary a lot seasonally. It will help us understand the complexity of the food webs, and how human changes to watersheds in turn change food availability.”

The Gar Collector

I’d seen Solomon in action in the lab, on a fishing boat and on social media. Now it was time to join him for his favorite: fieldwork. The previous day I presented a science communications lecture to Nicholls biology graduate students. This morning it was time to go afield with the gar professor.

I met Solomon, Thea Fredrickson and grad student Andrew Cumberland at Nicholls State on a cloudy Saturday morning, and we quickly headed out to a boat ramp on Bayou Chevreuil in the Upper Barataria watershed. Fredrickson would be running the boat through the season, and was learning how to unload and run it.

Wildlife research is often portrayed as a life of grand adventure, of wild places and wild animals and narrow escapes. No doubt, there is certainly plenty of excitement. But the reality is that, as with any research, wildlife studies also involve a lot of pure tedium.

The first part of the trip involved checking gear, prepping notebooks, taking water samples and temperature, reviewing safety protocol, setting the day’s collecting goals and making sure everything was in place for a day of fieldwork.

The mood on the boat was light, buoyed no doubt by Solomon’s enthusiasm. We motored up the river to a stretch with a large number of spotted gar. As is often the case in fish research, the collection is done by electrofishing. An electric pulse is sent into the water that temporarily stuns the fish. As they come to the surface, they’re netted.

Solomon and I stood at the front of the boat, rubber gloves on, nets at the ready. We’d capture (or attempt to capture) any fish that came up, regardless of species, but we needed to catch 30 gar for research.

Count your Gar

Cumberland flipped the generator on as Fredrickson slowly motored along one side of the bayou. “Remember to call out the number of gar you catch,” Solomon shouted above the generator.

I scanned the water and soon saw the first fish come to the surface, a bowfin, another primitive species also of research interest to Solomon. In a panic, I swooped my net towards the fish. The second it hit the water, the net wobbled at the surface resistance. The bowfin revived and darted underneath the surface.

A gar appeared. Cool. I swung and missed. Not cool. Another gar. Another miss. This was beginning to remind me of my short-lived Little League career.

Meanwhile, to my left, I could hear Solomon shouting out by number his gar captures. “One…two, three…four!”

How was he catching them so fast? I wondered. I glanced over and saw him lightly swishing the net, coming up with a gar and casually flipping it into the boat’s live well.

I tried to duplicate his technique. A gar surfaced. I swung and missed yet again. Then another fish appeared, this one seeming especially stunned. It was an easy target, even for me. I swooped my net over it and came up with a gar.

I silently congratulated myself on the catch, then realized I had to keep netting. I turned to empty the fish into the well, and it flipped over itself in the net, tangling its snout. Another gar came flying by, capture number twelve by Solomon.

I disentangled the gar and returned to work, eventually getting into a rhythm. We caught the 30 gar necessary for Fredrickson’s analysis, and returned to the boat launch. The students still had several hours of collecting muscle and fin samples ahead.

“I like to get even my general biology classes out in the field to collect fish,” Solomon says as we pull away. “It helps them appreciate the fish that are right in their backyards.”

As always, he’s building a new generation that respects and researches native fish. And as if to emphasize the point, as I get in my car to drive back to the airport, he hands me a small bag. A gift for my young son. Gar toys.

“Tell him to share some with his friends,” says Solomon. “Maybe he’ll make some new gar fans.”

In 2016, DH & son caught gar spawning at wetland in St Lawrence River. I suggested they forego making gar dinner, but apparently son persisted. Required tin snips(!) to remove skin. Apparently Indians used the skin for armour, pioneers on their ploughs! (According to son, the texture of flesh was like lobster or chicken, and taste was mild. Internet says eggs are poisonous, though! (Working on L Erie eons ago, I, too, was fascinated by the “rough” fish: gar, a school of young quillbacks, sheepshead, and, especially bowfin.)

To hook a fish, it’s snout makes it “more challenging and fun”. Certainly not for the gar. Can’t you just marvel at wildlife without having to harass it?

What neat fish! Have never seen pictures of them before.