Nets of diseased, lice-ridden salmon. Escapee fish polluting the gene pools of wild populations. Miles of mangroves bulldozed to build shrimp farms.

Aquaculture is often portrayed as an environmental risk, and if poorly managed, it can pose a serious threat to the surrounding ecosystem.

But aquaculture doesn’t have to be an environmental liability. A new paper from scientists at The Nature Conservancy and the University of Adelaide shows that aquaculture could be a valuable tool for conservation, restoring lost ecosystem services while providing food for people.

Is Aquaculture Bad for the Environment?

Many of the environmental concerns about aquaculture — and the resulting bad press — focus on salmon and other finfish aquaculture. But these species represent a very small portion of the overall industry. In fact, most aquaculture production focuses on seaweed and shellfish, like oysters and mussels.

Whether we like it or not, aquaculture is here to stay.

“Wild stocks alone just can’t meet the global demand for seafood,” says Robert Jones, The Nature Conservancy’s global aquaculture strategy lead. “They’re either producing at the maximum or in steep decline.” What’s more, he says that the demand for seafood is so great that even if conservation efforts to recover fish populations are successful, they still won’t produce enough fish.

Meanwhile, the potential for aquaculture to expand is enormous. Right now the oceans produce just 2 percent of human food but make up 70 percent of the planet’s surface. Aquaculture is the fastest growing form of food production, growing at a rate of about 6 percent each year. For comparison, land-based agriculture is lucky to grow 2 percent per year, and the land cleared to fuel that growth further harms the environment.

But this growth doesn’t have to spell disaster for nature, if aquaculture is done the right way. That’s because the environmental impacts of aquaculture can vary greatly, depending on the species, location of the farms, and specific management practices.

“We need to think about aquaculture as an interconnected part of the environment,” says Heidi Alleway, a scientist at the University of Adelaide and lead author on the paper. “There are so many positive things that can come out of aquaculture, but right now the dialogue is always negative.”

To help change that discussion, Alleway and her colleagues searched the scientific literature for case studies where aquaculture confers benefits to nature and then evaluated those benefits using a widely recognized classification system for ecosystem services.

Their results, published in BioScience, document the multitude of ways that aquaculture might serve as a tool for conservationists.

Improving Water Quality & Replacing Lost Reefs

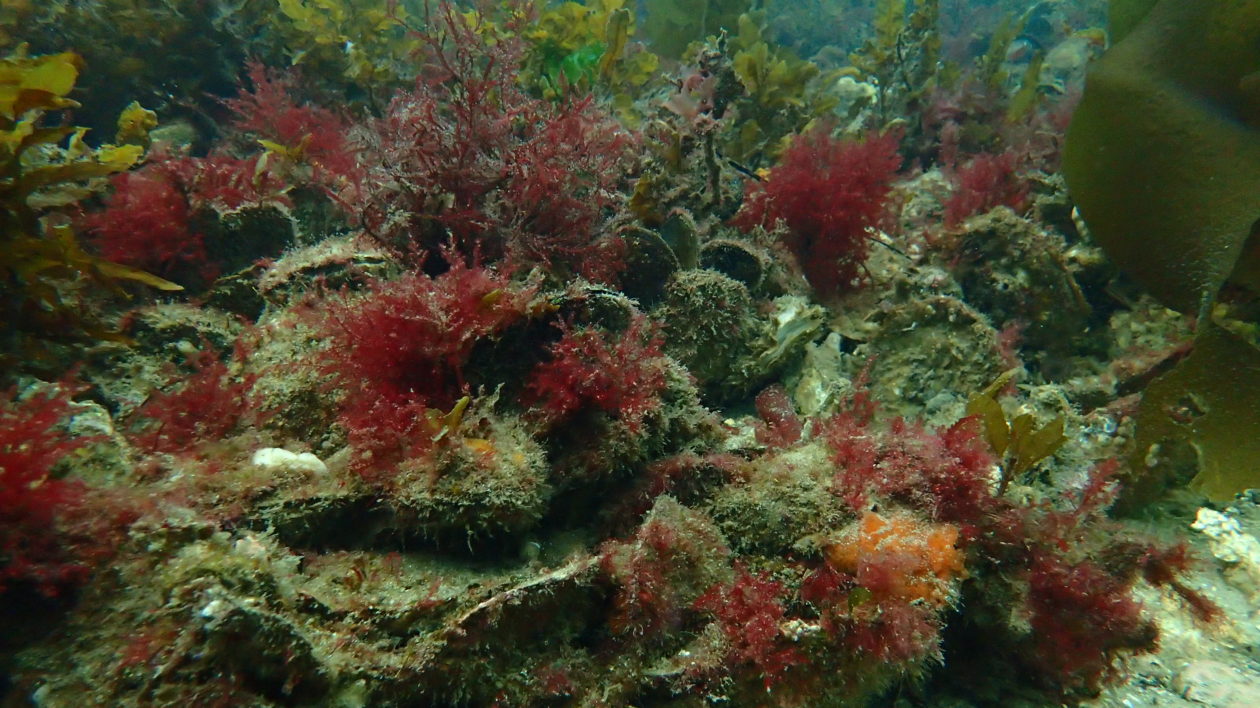

Shellfish have superpowers, at least when it comes to water filtration. Oysters, mussels and clams all suck in seawater, filtering out edible algae and nutrients and depositing what they can’t eat on the seafloor. “This process cleans up the water in a safe way, so you can still eat the oysters, but it also provides food for invertebrates, like worms and crabs, that then help feed fish,” explains Chris Gillies, marine manager for TNC’s Australia program.

But natural shellfish reefs are one of the most imperiled marine ecosystems on earth. About 85 percent of all shellfish reefs have either disappeared or been severely degraded, and in Australia that figure is closer to 95 percent.

TNC’s Australia program is pioneering new methods of restoring these historic reefs, but continental-scale restoration just isn’t feasible. “Restoration is expensive, and there are many estuaries where it’s not an option because the area is already zoned for another use,” says Gillies. “But we could use aquaculture to replace some of those water filtration benefits, and at the same time grow food.”

In places where excess nutrients are a problem, like the Chesapeake Bay, shellfish aquaculture could even help offset the negative environmental impacts of other industries. Natural reefs help protect shorelines from storm surge and erosion, and they also provide habitat for commercial and recreational fish species. The researchers say that aquaculture installations could perform some of those same services.

Providing Habitat & Capturing Carbon

In addition to replacing lost ecosystem services, aquaculture can create additional habitat for marine life.

Belize’s spiny lobster fishery is in steep decline, threatening the already-marginalized fishermen who rely on the industry as their sole source of income. TNC started a seaweed farming program to help provide alternative livelihoods for these communities. But the farms are also providing extra habitat.

“These farms draw in a ton of marine life,” says Jones. “We’re finding lots macroinvertebrates and juvenile reef fish.” But they’re also providing habitat for the one species the fishermen care about: the lobsters.

“So not only are can seaweed farming can help supplement livelihoods,” says Jones, “but it could play an important ecological role in helping rebuild that fishery.”

Marine macroalgae also play an important role in coastal carbon cycling and have been identified as carbon sinks. While more research is needed, the authors propose that seaweed and algae farming could be a potential tool to capture and sequester oceanic carbon dioxide.

“For example, what if we could work aquaculture into current designs for coastal engineering in a way that enhances ecosystem services?” asks Alleway.

Next Steps for Conservation & Aquaculture

The next step for conservationists is to figure out how to optimize aquaculture to provide the maximum environmental benefit with a minimal amount of harm.

Which types of aquaculture deliver the most conservation benefit? How big do farms need to be? And where should they be placed? “We need to start experimenting,” says Gillies. “We need to partner with farmers, implement what we already know works, and measure the impacts to see if it really is a better way of farming.”

In the Chesapeake Bay, TNC is working with four shellfish farmers to assess the water quality benefits of using different sizes and gear types. And in Belize, scientists are measuring species abundance and diversity in and around the farms to understand just how much habitat they provide. They are also monitoring farms to ensure there are no negative impacts on the surrounding environment, especially seagrass and coral.

Conservationists also need to build recognition of aquaculture’s benefits into regulation and policy frameworks. For example, Alleway used to work for the South Australian government evaluating applications for aquaculture licenses.

“We had a list of nearly 40 risk events that we would assess each new proposal against, and one of those was water filtration,” she says. “We had to evaluate the potential negative impacts of bivalves filtering the water, but there was no process in place to consider the potential positive value of that service.”

Part of that process will involve figuring out ways to value aquaculture’s contributions to nature. Scientists already estimate that the ecosystem services provided by marine and coastal habitats — like coral reefs, seagrasses, wetlands — are worth $50 trillion per year.

If done correctly, aquaculture could be the rare case where food production actually benefits the environment, instead of causing harm. “Aquaculture has a really big role in the future,” says Jones, “and we are just at the beginning of it.”

Aquaculture is deserving of its bad name. Too often fish farms are located in places without adequate mitigation for spread of diseases, polluted runoff from excess feed and fish feces, and spread of inferior genetic material.

Very interesting article. But with the oceans and the surrounding ecosystems as polluted and damaged as they are, we need to be extremely careful not to add to that damage in the process of experimenting to produce all this seafood that is so popular.

AND~ you need a proofreader! I’d be happy to fill that role, if you need one!