When coal seams are ripped from the earth, rocks containing sulfur-bearing minerals get exposed to air and water, creating toxic cocktails of sulfuric acid and dissolved metals, usually iron.

This acid mine drainage (AMD) can excise all life from a stream. And even where the kill is incomplete, iron precipitate can render the streambed unfit for fish spawning and benthic life by coating it with an armor-like layer of red, orange or yellow sediment — “yellow boy,” as it’s called.

AMD also dissolves such toxic metals as copper, lead and mercury, poisoning ground and surface water.

Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Ohio, Kentucky, Maryland, Indiana, Illinois, Oklahoma, Iowa, Missouri, Kansas, Tennessee, Virginia, Alabama and Georgia are blighted by AMD.

Rebirth of the Cheat

But some spectacular remediation is underway, especially in Appalachia. Consider the rebirth of West Virginia’s Cheat River.

In the 1990s the Cheat was dead. Canoers and kayakers had to tote bottles of fresh water to wash the acid out of their eyes.

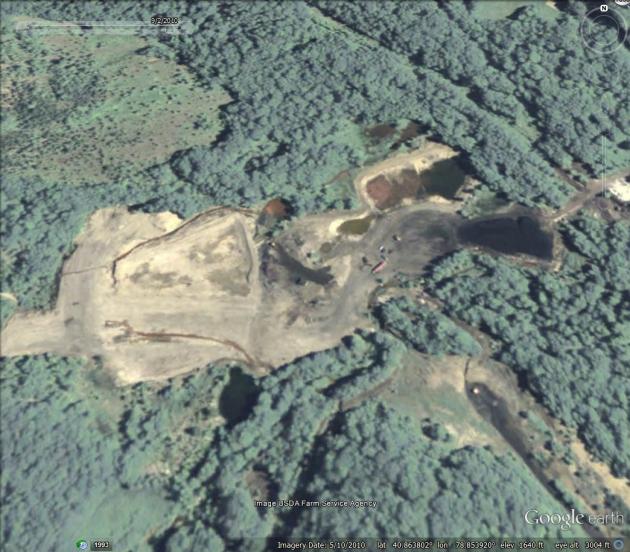

Fifteen years ago, as the Cheat started to recover, Trout Unlimited activist Bill Thorne and I stood on a high bank beside the “T & T site,” watching AMD, partially treated by the state Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), gush into Muddy Creek, the source of 40 percent of the Cheat’s acid load.

T & T Fuels Inc. owner, Paul Thomas, and his mine superintendent, Clyde Bishoff, had circumvented costs and The Clean Water Act by piping their AMD into an abandoned mine. It worked splendidly until April 1994 when the side of the mountain blew out. There was a second blowout in March 1995. The pH of Cheat Lake, 20 miles downstream, dropped to 4.

Thomas was sentenced to six months home detention and 4.5 years of probation; and both he and Bishoff were heavily fined. T & T Fuels forfeited its cleanup bond, required by the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act (SMCRA) of 1977.

The disaster propelled the Cheat to American Rivers’ list of most endangered rivers and inspired formation of Friends of the Cheat, a group that works to protect and improve the watershed, especially by raising money to treat AMD from bondless, pre-SMCRA abandoned mines.

DEP’s Office of Special Reclamation took over the T & T site, doing its best with remediation. But its “best” wasn’t good enough according to a court ruling. As the new owner, DEP had to meet clean-water standards like any mine owner.

So now DEP is putting the finishing touches on a state-of-the-art, $9 million treatment facility that, with pre-dissolved limestone slurry and two 80-foot-diameter clarifiers (like you see at sewage-treatment plants), will resurrect the lifeless lower 3.4 miles of Muddy Creek, connecting the Cheat with upper Muddy’s six miles of pristine brook-trout water. And AMD from nearby tributaries will be piped in for treatment.

The iron, aluminum and manganese precipitate will be pumped from the clarifiers up into the abandoned mine.

“A Scene Beautifully Grand”

Working with 50 landowners who have voluntarily contributed their properties, Friends of the Cheat has facilitated 16 treatment projects on pre-SMCRA acid sources. Fifteen of these projects are “passive,” meaning limestone-lined channels and wetlands do the work. One is “active,” meaning a “doser,” a silo-like structure kept full of crushed limestone, automatically buffers as needed.

When Thorne and I toured the Cheat watershed in 2003 some of the passive projects were starting to fail because they were clogging with yellow boy.

These days AMD is pushed through limestone leach beds, then sent to settling ponds that collect the precipitate. Dosers worked well then and now, but they require much operation and maintenance.

“Nowhere in all this fair land of ours has a scene more beautifully grand broken on the eye of poet or painter,” wrote Philip Kennedy in 1852 of the canyon cut by the Blackwater River. On his exploration of this Cheat headwater he reported that his party took 350 brook trout in a single afternoon.

Thorne and I were filled with hope when we inspected the passive project on Blackwater’s grossly acidified North Fork. But it wasn’t long before this three-quarter-mile limestone trench and wetland armored up with yellow boy ceased functioning. Now Friends of Blackwater is designing a modern passive project that will drop the yellow boy in settling ponds.

Five years after our visit the flow-activated limestone-grinding drum station on Blackwater’s mainstem, that partially neutralized AMD from Beaver Creek, was replaced with a more efficient doser that made the canyon better able to sustain at least hatchery trout.

And Friends has recently entered into a partnership to deal with multiple AMD seeps upstream on Beaver Creek. The group’s hydrologist, Ian Smith, believes this new treatment will allow remnant brook trout, that persist in the headwaters, to repopulate the whole flow. “Once chemical treatment succeeds,” he says, “we’ll also need to provide shade because of all the past logging.”

Walleyes Return

For 60 years environmentalists, anglers, hunters, birders, hikers, whitewater rafters and boaters had dreamed of protecting the 3,836-acre Cheat River Canyon, treasured for its beauty and biological richness. Early in the 21st Century this nearly happened. The state was narrowly underbid by Allegheny Wood Products, which promptly began razing the forest.

But the forest is habitat for the federally threatened Cheat three-toothed land snail. Citing Endangered Species Act violations, environmental groups sued. As settlement the defendant sold the land to the Forestland Group, an enlightened outfit committed to sustainable forestry and wildlife conservation.

In 2014 The Nature Conservancy, the Conservation Fund and other partners acquired the property and transferred ownership to the state. The Conservancy retains 1,361 acres of the canyon as its Charlotte Ryde Nature Preserve, a stronghold for the threatened snail.

Now that timber isn’t being hacked out of the canyon, acid-producing pyrite and sandstone soils no longer bleed into the river.

Today the pH of the Cheat has increased to the point that warmwater fish abound.

Friends of the Cheat director, Amanda Pitzer, told me this: “Last week [mid-May] some friends paddled 50 miles from Parsons to Kingwood. They couldn’t keep the smallmouth bass off their lines, almost got tired of catching them. The fishery on the Cheat is amazing. We now have walleyes [especially sensitive to acid] reproducing from Cheat Lake all the way up into the canyon.”

More Recovery

West Virginia’s Three Fork Creek, a Tygart Valley River tributary, is on the verge of complete recovery thanks to the combined effort of DEP’s Office of Abandoned Mine lands and Reclamation and Save the Tygart Watershed Association.

In 2010, before four dosers went in, a survey turned up one green sunfish in 12 miles of Three Fork Creek. Less than two years later, with the four dosers online and no fish stocking, a follow-up survey documented 1,605 fish representing 21 species.

A fifth doser, to be placed upstream in the watershed, will allow brook trout to navigate the mainstem and share genes with isolated feeder-stream populations.

So many acid sources enter West Virginia’s Middle Fork River that neither passive treatment nor dosers are practical. So for 20 years the state DNR and the Office of Abandoned Mine Lands and Reclamation have been adding limestone sand directly to the flow at 47 sites, thereby recovering 30 miles of mainstem and 89 miles of tributaries.

“Now we have brook trout moving between tributaries,” says Rob Rice, director of DEP’s Division of Land Restoration. “Those dump sites became part of the substrate. So we’ve created an alkaline bed to the point that we don’t have to dump sand every year. We can alternate years. We’ve also been doing land reclamation to reduce the need for limestone sand.”

Smooth Rock Lick, which used to funnel brook trout into West Virginia’s Buckhannon River, became an AMD casualty decades ago. In 2009 a survey team led by DNR biologist Jim Walker turned up no fish. Soon thereafter the Buckhannon River Watershed Association facilitated work on a passive system.

In 2015, three years after project completion, Walker’s team found the stream teeming with creek chubs, blacknose dace, white suckers and striped shiners. The following year it electro-fished brook trout from nearby Bearcamp Run, transferring them to Smooth Rock Lick. In September 2017, the team found young-of-the-year brook trout.

Much of the Susquehanna River system is polluted with AMD, but good things are happening there as well.

Among the more impressive success stories is the resurrection of Pennsylvania’s Bear Run.

Tom Clark coordinates AMD work for the Susquehanna River Basin Commission — an interstate body, with representatives from New York, Maryland, Pennsylvania and the federal government, that manages environmental stewardship and economic development on river and watershed. He offers this: “We’ve completed nine treatment projects on 15 miles of Bear Run and done some major land reclamation.”

Bear Run remediation was especially challenging because different types of runoff, required different treatment. Higher in the watershed runoff had decent pH but was loaded with iron, necessitating settling ponds and wetlands. Further downstream AMD was contaminated with aluminum, necessitating limestone beds. Further downstream still AMD was bad enough to require dosers.

“The South Branch had been devastated,” reports Clark. “So we put eight of our nine projects there — two aerobic wetlands, three limestone drains, two silos [dosers] and land-reclamations, planting oaks, cherries, maples and blight-resistant chestnuts from American Chestnut Foundation. After we got water quality pushed up in South Branch, North Branch brook trout moved in and repopulated the entirety of Bear Run.”

Fifteen years ago I could not have imagined the amount or quality of AMD remediation that has occurred in Appalachia.

Still, all is not well there. For example, about 2,500 miles of AMD-impaired stream remain in West Virginia, 3,000 in Pennsylvania.

As Churchill, declared after the British ran Rommel out of El Alamein, “This is not the end, this is not even the beginning of the end, this is just perhaps the end of the beginning.”

Every weekend i used to pay a visit this web page,

as i wish for enjoyment, as this this web page conations truly pleasant funny information too.

Need more help and funding to expand this effort

Being a WV resident and loving to catch those beautiful natives and loving the streams they live in it’s great to read a positive story about WV. Tired of reading how poor and backwards we are and about all the drug od’s.

Great article. Keep on cleaning up rivers and streams