“Tragically,” laments Freedom for Animals, “birds in zoos are prevented from flight… They have the ends of their wings chopped off.”

“Zoos have had little to no success with captive breeding programs,” proclaims One Green Planet.

Such zoo bashers seem stuck in the distant past and apparently haven’t heard or don’t want to hear about the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA).

AZA holds members to the highest standards of animal welfare, husbandry and veterinary care. And it has stunning success breeding imperiled species, reintroducing them to the wild and, where all habitat has been lost, at least maintaining the animals and/or their frozen sperm and ova until habitat gets restored.

“The wild is no longer safe for some species,” declares Lou Perrotti, Director of Conservation Programs at the AZA-accredited Roger Williams Park Zoo in Providence, Rhode Island. “A hundred elephants are being dropped a day, and the only way you can protect rhinos is to assign an armed ranger to each animal.”

In the last half century major zoos have transformed from menageries to educational facilities that approximate native habitats.

“For an urban child ET, the extra-terrestrial, is more real than the giraffe they see on TV,” says Brian Rutledge, president of Boston’s Franklin Park Zoo from 1995 to 2001 and now a National Audubon Society vice president. “ET at least communicates. The only way these kids will see a giraffe is at a zoo.”

When I was taken as a child to the Franklin Park Zoo in the 1950s it was basically a jail. When the Boston Zoological Society took over in 1970 it condemned a dungeon of a lion house built in 1903 and began work on a spacious, entirely African display. Soon after Rutledge arrived he game-fenced the zoo’s 12-acre lawn and moved incarcerated zebras and giraffes onto a replicated savanna.

Today 20 foreign zoos and 213 U.S. zoos (Franklin Park included) are AZA members, and similar accrediting organizations exist in Europe and Australia.

Despite improvements rendered by the Animal Welfare Act of 1970, some of the roughly 90 percent of American zoos lacking AZA accreditation are fair game for zoo bashers. But the distinction is rarely made.

“Research shows that with this younger generation our approval levels are going down the tube,” says Perrotti. “Some of these Internet warriors think they’re saving the planet while sitting at their desks. They’re quick to criticize but slow to research. And they’re raising the next generation.”

AZA’s mission is manifest in Perrotti’s work. For example, he oversees the breeding and successful reintroduction of endangered American burying beetles. And, had it not been for Perrotti’s zoo, New York’s Queens Zoo, The Nature Conservancy and other partners, the New England cottontail rabbit would probably be extinct.

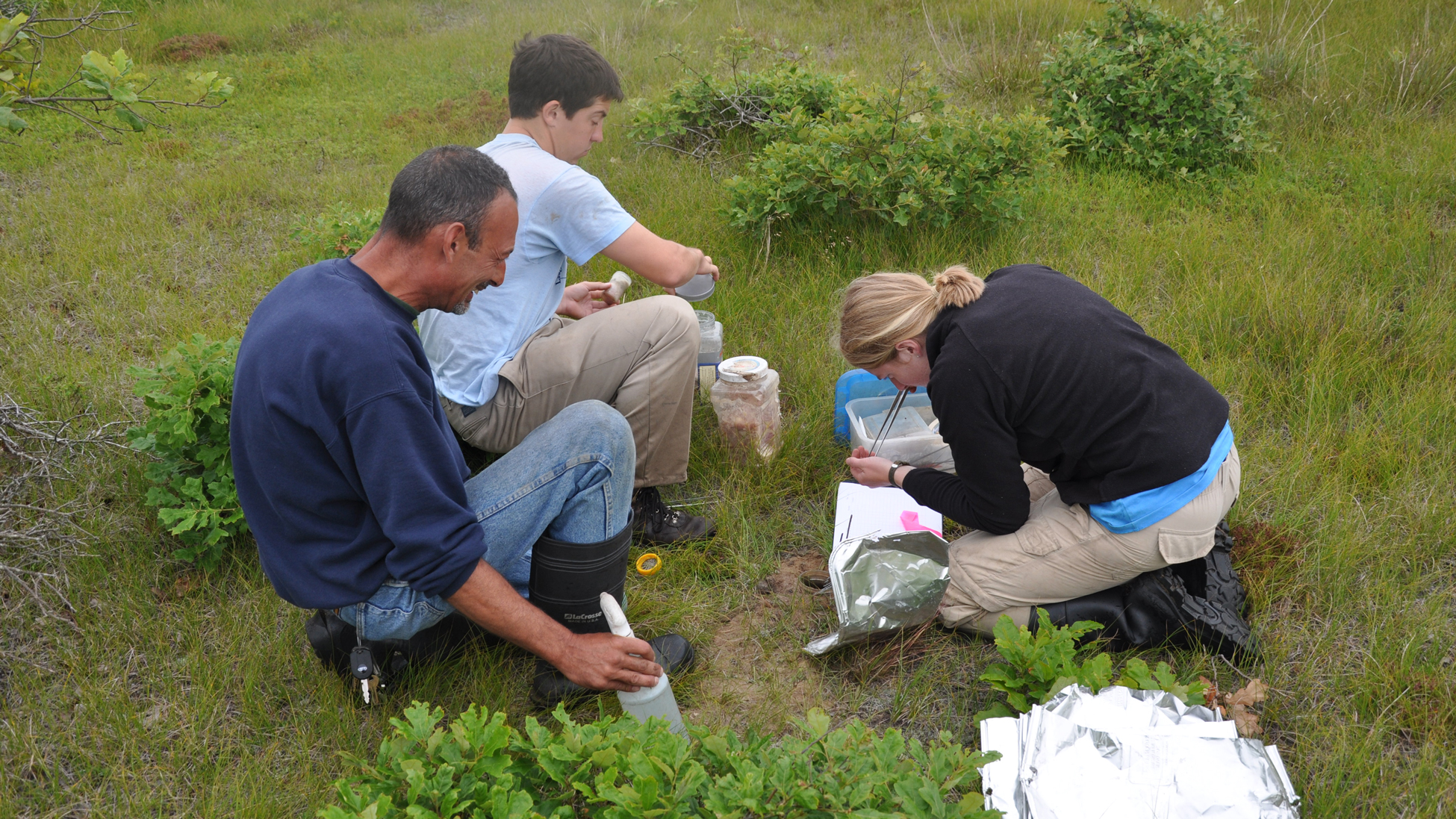

Partnering with institutions and other AZA zoos, Perrotti hatched and raised caterpillars of the endangered Karner blue, a butterfly that has declined 99 percent due to fire suppression, grazing and development. Pupae were delivered to restored pine-barren/lupine habitat in Ohio, Indiana and New Hampshire where reintroduced populations thrive.

“This year close to two thousand cold-shocked sea turtles were rehabilitated by aquariums and zoos,” reports AZA president/CEO Dan Ashe. “They’d be dead otherwise.”

Ashe, who directed the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service from 2011 to 2017, strengthens the alliance of wildlife managers and zoo/aquarium administrators.

To save frogs from chytrid fungus a coalition of AZA zoos, spearheaded by the Houston Zoo, built the El Valle Amphibian Conservation Center in Panama — a captive-breeding facility for imperiled species including the Panamanian golden frog, extinct in the wild.

Perrotti cringed when he learned the Center was importing non-native flies and crickets for frog food. When most of the insects died en route the Center began netting native katydid species, diminishing wild supplies by plucking the biggest breeders from grassy fields.

Perrotti, who co-chairs AZA’s Terrestrial Invertebrate Taxon Advisory Group, went to Panama and, with funds from his zoo and Disney, provided the Center with equipment and knowledge to breed native insects. Frog reproduction soared. Now the system is being replicated all over the world.

California Condor

In 1985, with only 22 California condors remaining on the planet, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service moved to evacuate them from the wild for captive breeding. That decision enraged a large element of the environmental community. Friends of the Earth founder David Brower advocated “death with dignity.” The National Audubon society delayed evacuation with a successful lawsuit that was eventually overturned on appeal.

Whatever “dignity” condors lost by being hatched and reared in zoos was well spent. Today at least 275 birds fly free in California, Arizona, Utah, and Baja California. Another 175 are captive.

Rodrigues Flying Fox

The Rodrigues flying fox is restricted to Rodrigues Island east of Madagascar. In 1979 it was Earth’s most endangered bat. Deforestation, cyclones and hunting for meat had reduced the population to about 70. Today, thanks to habitat restoration and captive breeding by British and American zoos, the wild population exceeds 20,000.

Giant Panda

Only about 1,800 wild giant pandas survive in 62 reserves which, with help from The Nature Conservancy, China is attempting to weave together into a “Giant Panda National Park.” The Chinese have had great success breeding pandas in zoos. Some 50 cubs were born last year, and now there are almost 575 captives.

But reintroductions haven’t gone well. “Hard releases,” in which captives are abruptly turned loose have failed.

Enter Dr. Ben Kilham of the Kilham Bear Center in Lyme, New Hampshire.

For 25 years the Center has been returning orphaned black bear cubs to the wild via soft releases in which they’re held in big enclosures and gradually conditioned to natural food, habitat and native wildlife.

“Young animals don’t have ability to travel on their own,” Kilham told me. “They’re afraid of other species, even woodpeckers. To fail at conditioning a bear to the wild you have to fail at socializing it with other bears. If you send out a dependent animal, it will come back. But that’s about food and survival, not love of humans. I don’t teach bears to be bears; the knowledge is inside them.”

Among the 165 black bear cubs the Center has successfully rewilded is “Squirty,” now 22. She’s produced 11 litters and still greets Kilham, even letting him replace her GPS-tracking collar.

In 2013 the Kilham Bear Center started teaching its techniques to panda managers. This has been harder than work in New Hampshire where state officials perceive parentless bear cubs more as problems than assets. In China the panda is a national icon, and there are many levels of governmental involvement with input about how and where animals should be tended and released.

Still, Kilham’s team — the Chengdu Research Base of Giant Panda Breeding and the Global Cause Foundation — is making progress. Kilham feels confident that soft-released pandas will, like Squirty, allow themselves to be examined and have their tracking collars changed without sedation. “Sedation is dangerous,” he notes.

The Kilham Bear Center’s panda work is featured in the new IMAX film “Pandas,” released in April.

Mexican Wolf

Without AZA zoos the Mexican wolf, once prolific in the Southwest and Mexico, would not exist. By the time the species was listed as endangered in 1976 it was virtually extinct in the wild. With only seven captured animals the U.S. and Mexico initiated captive breeding.

Today 27 AZA zoos and 26 other partners hold 281 Mexican wolves; and soft releases have established a wild population of 114 in New Mexico and Arizona and 31 in Mexico.

With only seven founder wolves, inbreeding is a concern. Remedial strategies include “cross fostering.” Young pups from one litter are transferred to another, and raised by the foster parents.

In May 2017 two Mexican wolf pups born to “Zana” at the Brookfield Zoo near Chicago were successfully cross-fostered to a den of New Mexico’s San Mateo wolf pack. Two pups from that wild litter were taken to the Brookfield Zoo to improve the captive gene pool.

And this year the Brookfield Zoo performed one of the first artificial insemination procedures with Zana, utilizing frozen semen from a long-dead male — a huge step toward avoiding future genetic bottlenecks.

“There still are many illegal killings and significant political pressure to delist,” reports Joan Daniels, Brookfield Zoo’s Curator of Mammals. “And there’s only a very restricted zone where the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is allowed to release wolves. Mexico faces the same issues. But when you start with seven animals and have almost 300 now in professional care, that’s an incredible accomplishment.”

The Fish and Wildlife Service will delist the Mexican wolf when the Arizona-New Mexico population and the Mexican population hit annual averages of 320 animals and 200 respectively.

A Force for Conservation

“Breeding and releasing animals is an important role for zoos,” says Steve Burns, president/CEO of Hogle Zoo in Salt Lake City and former AZA board chair. “But it’s a last-ditch step. I think AZA’s greatest role is educating our 200 million visitors.”

Educated zoo visitors, he observes, become activists.

As director of Zoo Boise in Idaho Burns implemented the nation’s first zoo conservation fees. When he left in 2017 the zoo was generating almost $300,000 in conservation funds a year. Collectively, AZA zoos and aquariums annually generate $216 million in conservation funds, and Burns says there’s potential for $500 million.

The money is used outside zoos for things like habitat protection and restoration and hiring anti-poaching units. For example, Zoo Boise helped fund the recovery of Gorongosa National Park in Mozambique, which had been one of Africa’s greatest wildlife sanctuaries until it was trashed in a civil war and its mammals killed and eaten.

“I’ve been to Gorongosa four times now,” says Burns. “And the dramatic comeback of wildlife has given me hope. Give nature time and space and it will heal.”

As the zoo bashers observe, nature doesn’t exist inside zoos and aquariums. But because of zoos and aquariums and the people they educate it is healing on the outside.

That was a great, informative article but, it was difficult for me to read.

People who criticize Zoos are ignorant. Zoos in the US and Europe and Wildlife Preserves around the world are doing wonderful jobs of saving animals who would otherwise be extinct. How to best manage and preserve species is an ongoing learning curve. They learn from their mistakes. Keeping or putting animals back in their native habitant is a very risky business for many reasons. It would be the most desirable out come if we lived in an ideal world but we don’t. I would rather see animals live in protected environments than become extinct.

Thank you for explaining why some zoos are superb at conservation. I had never heard of the AZA. I was delighted to find out that a zoo I loved as a child, the Detroit Zoo, is now AZA accredited, and when I visited last year for the first time in decades, the conservation work being done was impressive. It’s wonderful to see credit being given to good zoo conservation work, and in such interesting detail.

Excellently written & very informative piece. I personally was not aware of AZA’s work. So thank you Ted for your efforts … & thank you to all those reading this article who are involved every day restoring various populations of animals to the wild.

A form of’soft’ release after hatching and raising eaglets with minimal human contact is largely responsible for the recovery of bald eagles. Similar work needs to be done for sage grouse, Monarch butterflies and other imperiled species.

A wonderful piece, and hopeful, too — thanks.