Carl LoBue made a disturbing discovery when he lifted the blue crab trap near his Long Island, New York home: seven diamondback terrapins, five of them dead and bloated and two close to death. All had swam into the baited trap, but were unable to escape back to the surface.

They drowned.

It was the late ‘90s on Long Island, and Lobue was acting director of the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation’s Marine Crustacean Unit. He had been asked by an elderly neighbor to move a crab trap that was blocking his boat. But as disturbed as LoBue was by the dead turtles, he also knew the law: even though crab harvest was under his jurisdiction, he couldn’t tamper with the dozens of crab traps that had been set the night before in a location he knew was home to many terrapins.

The crabber had broken no laws.

“I started looking into it and learned throughout their range, it was well documented that terrapins drown in crab traps,” LoBue says.

It was particularly troubling as climate is expanding the range of blue crabs, and trappers that follow, to the north side of Long Island where, in the absence of a historic blue crab trap fishery, terrapins had been more abundant and naive to the danger of traps.

“They were just being massacred here,” he says.

Fortunately, an easy solution was available—or so it appeared. As LoBue wrote on the Fire Island and Beyond blog:

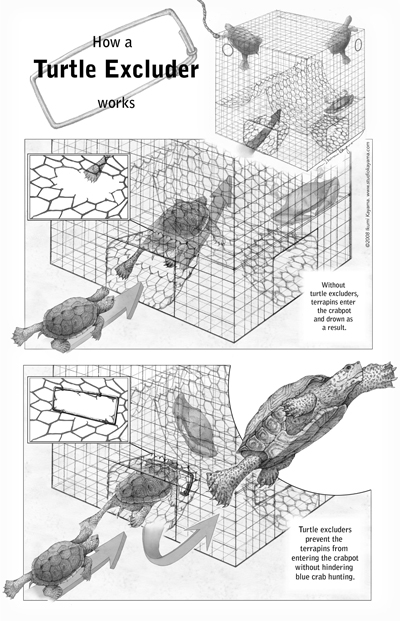

“Other states required that crab traps contain devices that constrain the size and shape of crab trap entrances so that crabs could still get in, but only the smallest sizes of terrapins could fit in. Studies had been conducted that showed these devices, known as By-Catch Reduction Devices, or Terrapin Excluders, had no negative impact on the catch of blue crabs.”

As acting director of the Marine Crustaceans Unit, LoBue made his case to other officials in the Department of Conservation. A proposal was put forth. “Who could argue this?” he thought. The science was pretty clear; excluding devices saved turtles and had no impact on crabs.

He was wrong. In the public comment period, crab fishermen opposed it, loudly and often. They claimed excluders were too costly. They claimed that research done in other states could not replicate the conditions of New York waters.

Most damning of all: They pointed to a New York State wildlife permit that actually allowed direct harvest of diamondback terrapins. If terrapins were in such trouble, why could an individual go out and specifically target them?

The proposal failed. LoBue accepted the futility of introducing a proposal again. He moved on. End of story. Or so he thought.

LoBue soon after left the state agency to work for The Nature Conservancy, where today he is the New York Oceans Program Director. Coincidentally, the issue of terrapin excluders would come before him again, in 2014. This time he had a game plan for what needed to happen.

First, there was the matter of the direct harvest of terrapins. The $10 harvest permit included a turtle season but no bag limit. Turtle hunters were catching them and selling them live in New York City markets as an exotic meat. Professional herpetologists verified that this commercial harvest was unsustainable and unjustifiable.

“This arcane law was an obstacle,” says LoBue. “We needed the science to make the case.”

More than 60 reptile experts signed a letter stating that the commercial harvest of terrapins had to end.

Next, LoBue recognized they needed the support of crabbers to avoid repeating history. As he tells it:

“We needed an open and honest dialog with crabbers. So, I offered to set up a meeting with commercial crabbers, [herpetologist] Dr. Burke, DEC officials, and Long Island naturalists John Turner and Mike Bottini. Although it was at times tense and awkward, we ate bagels, drank coffee, and listened to each other’s concerns. While some crabbers obstinately denied ever seeing or catching terrapins, others were more forthcoming, admitting they caught them and expressing remorse about unintentionally drowning them. Some did not like the style of excluders used in other states, they said they didn’t fit in their traps.”

This started a dialogue that typified the give-and-take approach of practical conservationists. No one would get exactly what they wanted, but overall terrapins would benefit. The proposal would require excluders in the ideal terrapin habitats – creeks and harbors – while not requiring them in other waters where terrapins were encountered less.

A key moment occurred when a professional crabber testified with his experiences based on a year of using the excluder devices. After testing several, he found one that even increased his blue crab catch.

“A lot of research has been done on excluders. There’s a lot of peer-reviewed literature,” says LoBue. “But facts and information don’t win the day. One fisherman speaking about excluders was more effective at changing minds than a whole stack of peer-reviewed papers.”

It’s a point that all who communicate about conservation and science should remember.

LoBue worked to ensure that obtaining and using excluders was as easy as possible. He writes:

“The Nature Conservancy, committed to fund the purchase of the metal excluder design that came out of this process. We contracted with a US manufacturer in who made them with US stainless steel. We even got help from a friend at Freeport Auto Parts and a local Boy Scout Troop to clean and tumble the sharp edges off them. And we produced a video featuring a Brookhaven crabber showing other crabbers how to install them, and where to get them for free. Our friends at Seatuck Environmental Association chipped in and purchased of thousands of the plastic style excluders used by fishermen in neighboring states. Both styles are being distributed to crabbers for free by NYS DEC.”

And then came the comment period, a complete reversal of the last time this proposal was put forth. This time around, well-placed blogs, photos, and a video shared widely on social media helped generate more than 1,600 comments in support of the regulation changes, with only 4 opposed.

Due to that hard work and public involvement, for the first time this year there will be no directed harvest of diamondback terrapins anywhere in New York, and terrapin excluders will be required on crab traps in prime habitats.

LoBue notes that the terrapins do face other threats. They have already lost habitat to coastal development. They need beaches to lay eggs, much like sea turtles, and sea walls built for storms and erosion control eliminate nesting habitat.

“But we just removed two big and direct threats to turtle survival,” he says. “It took a lot of persistence and dedication from many people. It is easier to kill a regulation than get it passed. By listening to and working with the crabbers, we were able to pass regulations that make a brighter future for turtles. My wife and I are already planning a kayak trip to our old spots to look for turtles.”

It’s time for change if we want to have a future!

Save the terrapins!!

This is amazing! Thanks for your wonderful, effective work on this issue.

please, help fight hard and get creative on ways to fight to stop all forms of traps, this is inhuman, cowardice, and brutal to trap any wild animal or sea life.