Around the Mediterranean and southern Europe, the temperature pushed above 100⁰F last week, with some reports of high temperatures in a couple locations reaching 109⁰F (43⁰C). In one notable anecdote told by the New York Times, it was hot enough in Rome that gum was spontaneously melting in its pack. This heatwave, cutely nicknamed “Lucifer” since it feels hellishly hot, has caused all manner of problems, from the minor (Italian art museums closed and Italy’s wine crop could be ruined) to the serious (deaths have been reported in multiple countries). We in the United States have our own heat wave, less well-named. Seattle and Portland, two cities not known for hot summer weather where relatively few people own air conditioners, hit 104⁰F and 107⁰F respectively.

While it is hard to attribute any single event like Lucifer to climate change, new science makes it abundantly clear that climate change has already made our summers hotter and riskier. James Hansen and colleagues just released an update of their curves of summer temperatures across the world (hat to New York Time for an excellent write-up here). Compared with the base period (1951-1980), two-thirds of our summers now are hotter than the previous average, and 15% are much hotter. In other words, what used to be a hot summer heat wave is now just normal summer weather.

A trio of new climate modeling papers show just how hot climate change will make the world’s cities, and just how dire the public health consequences could be.

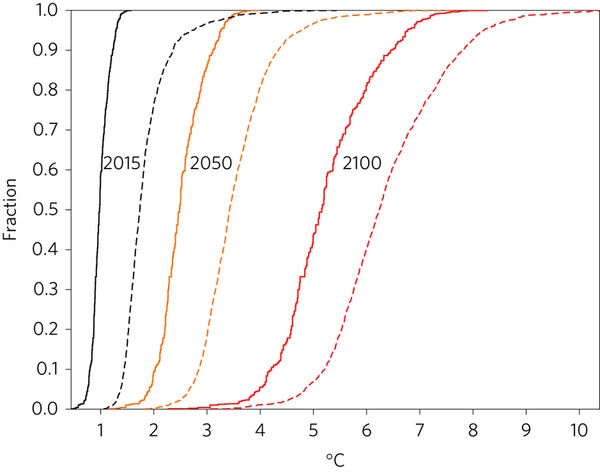

In May, a paper in Nature Climate Change forecast climate change impacts for major cities globally. There is a figure in this paper, Figure 2, that literally made me gasp when I saw it. It shows the cumulative distribution of temperature changes and increases in the urban heat island (which happens when impervious surfaces store the sun’s energy and then later reradiate it as heat, which is what makes cities hotter than rural areas) in the world’s cities in 2050 and 2100. If I am reading this right, the temperature in cities might increase by 11⁰F (6⁰C) in 2100 on average, but 10% of the time the increase would be greater than 14⁰F (8⁰C). If a typical heat wave in Washington (DC), my home town, is now around 100⁰F, then in 2100 we should be used to 110⁰F heatwaves.

Finally, a recent report in the Lancet modeled the toll such hotter temperatures might have one human health. It focused on Europe, and predicted that unless cities begin to adapt, deaths due to warm temperatures could rise from about 2,700 a year now to more than 151,000 per year in 2100. In other words, climate change might increase the risk of mortality from heat waves more than 50-fold.

The key words there is “unless cities begin to adapt.” It is possible for cities to weather quite high temperatures without large increases in mortality, if they are ready. Those of us in the conservation movement have been talking a lot about urban street trees and parks as climate adaptation measures, as ways to reduce air temperatures. And indeed, The Nature Conservancy’s work in the Planting Healthy Air report shows that trees are providing meaningful health benefits to millions in cities. But the average reduction in air temperatures is likely only 1-4⁰F (0.5-2⁰C). This clearly only begins to blunt the risk of higher temperature due to climate change, which could increase temperature 11⁰F (6⁰C) on average by 2100. Cities around the world need to begin actively creating heat action plans, including planning for emergency cooling centers so that those without air conditioning or fans can get to safety.

Climate change is here, and it is only just beginning. It’s time for the world’s cities to get ready.

Of course, cities must be prepared, together with other inhabitants of the entire planet. After all, the climate is changing everywhere. When I studied this question, I found the program “It is coming” https://allatra.tv/en/video/it-is-coming and realized that the future would affect everyone. And that it is important to be ready internally, ready to lend a helping hand to all who need it. And learn to live in peace with everyone right now.

Trees have always been a plus in nature and protection from it!! I live in a city in S. Fla., called Coconut Creek, which prides it selves as an arbor city, so we are very protective of our trees, with strict rules on trimming and removal. PERMITTS REQUIRED FOR BOTH FIRST!! RESPECT THE TREES ALWAYS!!!

Dr. Robert Mc Donald, su estudio y sus conclusiones son muy interesantes y para Monterrey, México, son aplicables aunque infortunadamente no tenemos los medios y la cultura para llevar registros de los cambios sutiles pero progresivos que estamos teniendo en el clima urbano. quisiera saber si existen estudios a nivel árbol y su entorno, esto es, datos o registros sobre lo que se dice en general y que es cierto; que los árboles de algún modo y en virtud de su actividad fisiológica modifican favorablemente el clima. creo que en la medida que demuestremos a la sociedad y a los gobiernos locales los beneficios evidentes de los árboles, podremos lograr una reacción mas positiva hacia procesos de forestación urbana. en mi casa esta demostrado que los árboles asociados a fuentes de agua son el mejor hábitat para aves, especialmente en periodos de crisis de agua y altas temperaturas.