Water striders are one of the most interesting and enjoyable aquatic creatures to observe. Best of all, they’re found widely across the Northern Hemisphere – in lakes, creeks, urban ponds, water features and even mud puddles.

Their lives on the water’s surface make them easy for even a young child to observe. Last week, my two-year-old and I watched a throng of water striders (also known as water skippers or pond skaters) on a small, local canal. Even though the canal was just beginning to fill with water, the water striders were already there.

There have been some 1,700 species of water striders identified. While they superficially resemble spiders, they’re actually insects, members of the family Gerridae.

Here are seven cool facts about water striders.

-

How water striders walk on water

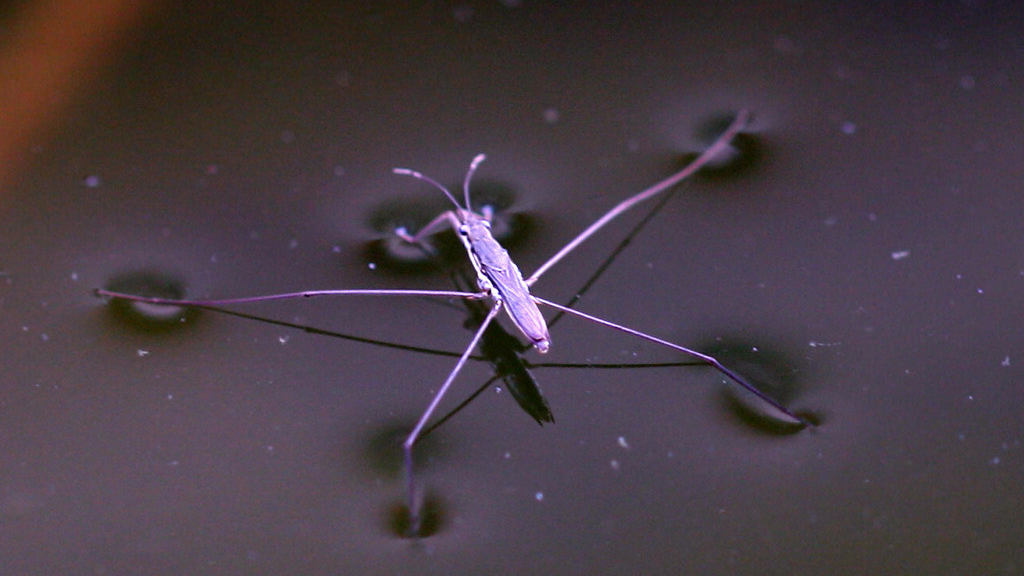

Photo © Jin Kemoole / Flickr through a Creative Commons license The first thing you notice about water striders is their rapid skipping across the water surface. Most insects of a water strider’s weight would quickly sink and drown. How do they stay on the surface?

Recent research provides the answer. Water strider legs are covered in thousands of microscopic hairs scored with tiny groves. As reported in National Geographic, “These groves trap air, increasing water resistance of the water’s striders legs and overall buoyancy of the insect.”

The water skipper’s legs are so buoyant they can support fifteen times the insect’s weight without sinking. Even in a rainstorm, or in waves, the strider stays afloat.

If a water strider’s legs go underwater, it’s very difficult for them to push to the surface.

Their legs are more buoyant than even ducks’ feathers.

The ultra-floatation capabilities of water skipper legs may have applications for human use, such as self-cleaning surfaces and antidew materials.

-

More about those legs

Photo © Alexander / Flickr through a Creative Commons license The strider’s legs do more than repel water; they’re also configured to allow efficient and rapid movement across the surface.

As with all insects, the water strider has three pairs of legs. The front legs are much shorter, and allow the strider to quickly grab prey on the surface. The middle legs act as paddles. The back legs are the longest and provide additional power, and also enable the strider to steer and “brake.”

The buoyancy and paddling legs allows striders to be fast. Very, very fast. The National Geographic article reports striders are capable of “speeds of a hundred body lengths per second. To match them, a 6-foot-tall person would have to swim at over 400 miles an hour.”

Unfortunately for the water strider, these extraordinary capabilities don’t extend to land. Their legs are almost useless on hard surfaces.

-

Water striders are efficient predators

Photo © Aiwok (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons That speed is essential for the strider’s most important task: snatching prey off the water’s surface. While striders don’t bite people, they are highly efficient predators. A water strider rapidly grabs a small insect with its front legs, then uses its mouthparts to pierce the prey’s body and suck out its juices.

They are particularly effective predators of mosquito larvae. As the Backyard Arthropod Project blog writes, “Since mosquito larvae breathe through a snorkel that they poke through the surface of the water, the water striders can grab them by the snorkel and eat them. I approve of this.”

As do I. It’s always good to have some striders around. However, if there are too many water striders around and they run out of mosquito larvae, they eat each other.

-

Their courtship is not very romantic

Water striders using surface tension when mating. Photo © Markus Gayda [CC-BY-SA-3.0], via Wikimedia Commons Even people who are normally creeped out by insects tend to enjoy water striders. Everything about them seems pretty benign. Except for their mating habits.

If you watch a pond’s water striders long enough, you often see two water striders on top of one another. Yes, that’s what you think it is. However, females have evolved a “genital shield” to guard against unwanted males mating with them.

The male water striders have coevolved a strategy so that the female is more likely to submit to advances. The male taps the water’s surface in a way attractive to aquatic predators. Since the female is beneath the male, and nearer the water, she will be the one first gobbled up by a fish or other hungry creature. Thus, it behooves the female to submit quickly and not deploy the shield (or “insect chastity belt,” as one reporter put it).

For water striders, love is a battlefield. Ecologists call this “antagonistic coevolution.” Popular bloggers call this a lot of things, many of them unsuitable for a family audience.

-

They can fly, too. Sometimes.

Photo © arian.suresh / Flickr through a Creative Commons license Many strider species have wings of varying lengths, depending on habitat conditions. Species frequenting calm waters typically have large wings. Species that live in swift waters have short ones, as long wings could be easily damaged.

But other species have wings only when they’re likely to need them. Called polymorphism, it is the mechanism that enables a parent to have one brood of young without wings, while the next brood has them. This allows water striders to be very adaptable to changing water and habitat conditions.

For instance, if the strider is living in small wetland and temperatures are rising, the habitat is likely to disappear. Thus a mechanism is triggered so the next generation of water striders has wings, allowing them to fly away from their drying wetland. But if the wetland is lush, wet and expansive, the strider has young without wings – the wings take more energy to maintain, and there’s no benefit to having them if they aren’t needed.

This capability allows striders to colonize all sorts of aquatic habitats, including tiny ponds and even mud puddles. If the habitat doesn’t last, the next generation has the ability to move on.

-

Water striders could be flying over you, right now

Water striders on the Congaree river near Columbia, South Carolina. Photo © Hunter Desportes / Flickr through a Creative Commons license Entomologist Gilbert Waldbauer, in his readable natural history book A Walk Around the Pond, shares this story from his friend James Sternburg.

“Every spring, Jim … thoroughly cleans and fills his plastic-lined pond with freshwater. Year after year, adult water striders arrive within a day or even minutes after the pond is filled. He has told me, with what I think is only a little exaggeration, that ‘the air must be crowded with cruising water striders looking for a pond.’”

I’ve noticed this, too. When my son and I checked out the local canal, it was just beginning to fill, yet water striders were already occupying every pool of water. I’ve found striders on puddles in arid high desert mountains, miles from running water. How can they find these new habitats?

Waldbauer points to research that suggests aquatic insects are attracted to any reflecting surface. If a strider sees such a surface, it checks it out. It suggests that Waldbauer’s friend is probably not too far off the mark, either. If you live in the Northern Hemisphere, right now there’s probably a number of water striders flying around over you, looking for new water to colonize.

-

Water striders take to the sea, too

Halobates sp. Photo © Cory Campora [CC BY-SA 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons It’s common to hear biologists say that our planet is dominated by insects. And it’s hard to argue: after all, there are at least 900,000 insect species, accounting for 80 percent of the world’s known species. The sheer numbers of ants, termites, bees and other species is staggering.

But this is true only on land and in freshwater habitats. By sea, insects are often conspicuously absent. Of those 900,000 species, only a few hundred are found in the ocean.

Some water strider species are among them. These species lack wings and can be found far out to sea. There is some disagreement as to their habits and diet, but many sources suggest they feed on fluids secreted by dead floating animals.

Join the Discussion