Of all North America’s Atlantic salmon rivers none compared in size or productivity with the 407-mile-long Connecticut River that drains Vermont, New Hampshire, Massachusetts and Connecticut. But early in the 19th century all strains of salmon uniquely adapted to this sprawling system (at least 25) had been rendered extinct by dams.

Salmon restoration on the Connecticut began in earnest in 1967. It was a dream that energized the fishing and non-fishing public and elicited enormous investments of time and money from feds, power companies and the four states. The partners obtained fertilized eggs from northern rivers (most recently Maine’s Penobscot, the nearest) and reared and stocked millions of juvenile salmon, taking eggs and milt from the few returning adults and rearing more. Each generation was better-adapted. In 1980, 529 adults returned. Success seemed assured.

Then something went dreadfully wrong at sea. Young salmon thrived in a river cleansed by federal law and reconnected by fish lifts and ladders. They just vanished when they hit saltwater. By 2012 the Connecticut River run numbered only 54, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service pulled the plug. A similar restoration effort was abandoned on the Merrimack River, which drains New Hampshire and Massachusetts.

“In my mind a major factor has been climate change,” declares Connecticut’s supervising fisheries biologist Steve Gephard. “We’re at the southern extent of the range. Long Island Sound is getting warmer every year.”

As returns dwindled, managers were pilloried by the hook-and-bullet press. “Sportsmen ought to be incensed at this waste,” asserted one well-known outdoor writer in 2002. “It would be better to use the money toward updating hatcheries and providing more trout.” He then scolded fish-lift operators at the Holyoke, Massachusetts dam for not dispatching sea lampreys which “literally suck the life out of their host fish.” After all, Maine was killing their lampreys.

A few salmon still return to 13 Maine rivers, but they’re federally endangered. In 2016 only 509 were counted in the Penobscot, 14 in the Machias, 12 in the East Machias and single numbers in the others.

But while Atlantic salmon recovery was failing, the monumental effort to make it happen created successes unforeseen and frequently unnoticed by critics.

“Salmon restoration was incredibly important for getting us in the diadromous-fish game,” says Gephard. “And it allowed us to develop expertise in fish passage. When I started 37 years ago, salmon were the charismatic species driving all fishways. In 1982 a flood took out a bunch of small dams, and I argued long and hard that if these dams were rebuilt, they should have fishways. I was told, ‘No, we don’t build fishways for anything but salmon.’ That’s changed.”

The Nature Conservancy’s Sally Harold, who directs river restoration in Connecticut, has completed 10 dam removals and 13 fishways.

Consider what such work has meant for fish other than salmon, especially in the Connecticut River. In 1967, 19,484 American shad were counted at the Holyoke Dam; in 2016 the figure was 385,930. In 1967 no gizzard shad were seen; in 2016: 598. The sea lamprey count has increased from 46 in 1967 to 35,249 in 2016. Upstream eel passage has increased from zero before ramp traps were installed at Holyoke in 2002 to 38,449 in 2016. Endangered shortnose and Atlantic sturgeon are tough to count, but fishways are boosting their numbers.

Blueback herring are tanking, but that’s apparently because they’re being killed as bycatch in the sea-herring fishery. “They’re doing great in Maine,” says Gephard. “They don’t go out of the Gulf of Maine much so they’re not as susceptible. We were very disappointed when the New England Fisheries Management Council recently voted to raise the allowable cap on bycatch. Our reaction was, ‘What the hell? We just went through one of the worst seasons for river herring [a collective term for bluebacks and alewives], and you’re allowing more to be caught.’”

In Maine, Project SHARE — a coalition of state and federal agencies, landowners and NGOs including The Nature Conservancy — has restored woody debris, removed old logging dams and replaced impassible culverts. Another coalition, also including the Conservancy, has protected 153,826 watershed acres through purchase and easement. These efforts were driven largely by salmon restoration.

In 2008 the Penobscot River Restoration Trust, of which The Nature Conservancy was part, purchased the three lower dams. The Trust removed the Great Works Dam between Old Town and Bradley in 2012 and the Veazie Dam just north of Bangor in 2014. Last year it completed a bypass around the dam at Howland.

This $64 million reconnection, the biggest ever undertaken in North America, has made 2,000 additional miles of habitat available to diadromous fish. Early results: In 2013 about 1,000 river herring were counted; in 2016: 1,803,063. In 2014 the sea lamprey count was 641; in 2016: 4,945. In 2013 no American shad were seen above Veazie; in 2016 the count was 7,868. Brook trout (resident and sea-run), anadromous smelt and tomcod aren’t counted, but their runs are surging.

The dream of Atlantic salmon recovery in the U.S. flickers on only in Maine. This from Dwayne Shaw, director of the Downeast Salmon Federation: “We’re doing what hasn’t been previously attempted — planting eggs in downeast streams, raising parr [juvenile salmon] in our hatchery, then stocking them in the rivers their parents came from. This strategy has worked so well on Britain’s Tyne River that we’re expanding our facility in East Machias to raise more fish.”

The Maine Department of Marine Resources now understands the value of sea lampreys and assists their upstream passage. Once these ancient fish enter rivers they can’t “suck the life” out of anything because they stop feeding, go blind and their teeth fall out. They die after spawning, delivering marine nutrients to tributaries.

“When researchers sampled a mile below lamprey nests they wondered why they couldn’t find a nutrient signal,” says The Nature Conservancy’s Josh Royte. “But when they sampled around the nests they learned that those nutrients get soaked up quickly by the starving ecosystem. Minnows and snails that grow up around lamprey nests are larger and produce more offspring. And when researchers set out fake lampreys made with seafood they found that juvenile salmon grow bigger and are more fit for their migration downstream.”

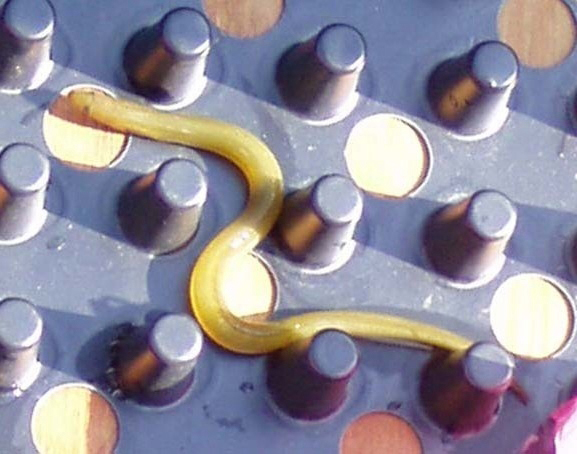

When lampreys make communal nests they clear silt from wide areas, creating spawning habitat for salmon and trout and better living conditions for mussels. Then larval lampreys, maturing in the substrate, filter impurities from the water column. When Gephard snorkels the Connecticut River system he sees lamprey carcasses covered with feeding caddisfly larvae.

Like larval lampreys, mussels maintain water quality by filter feeding. The alewife floater, eastern elliptio and state-listed species like the tidewater mucket, eastern pearlshell, eastern lampmussel and yellow lampmussel have brighter futures because of river reconnections that got started with attempted salmon restoration. Female mussels spew larvae (glochidia) which attach to fish gills and fins, then drop off and mature. In fact, part of the yellow lampmussel’s mantel mimics a minnow, complete with tail and eyespot. It waves this decoy, then blasts glochidia into the face of any fish that bites.

Eastern lampmussels are doing better because they ride a wide variety of fish that can now move more freely through river systems. Eastern elliptios are widespread and abundant for the same reason. Alewife floaters now abound in the Connecticut River because they can ride shad all the way to southern Vermont. Eastern pearlshells, which can outlive humans, are also doing well; they ride brook trout and other salmonids. The yellow lampmussel, a big-river species that rides white perch and probably yellow perch, striped bass and smallmouth bass, flourishes in the Penobscot system and in water impounded by the Holyoke Dam. Tidewater muckets are common in the lower Connecticut River; suspected hosts include alewives and banded killifish.

Mussels also benefit from nutrients delivered by lamprey carcasses, the carcasses of other diadromous fish that often don’t survive stress of migration and spawning, and eggs and milt of all species. “Where there are lots of fish, eagles and ospreys nest, and the juvenile birds are in better shape and less vulnerable to predators,” says Royte. “Where there are fewer fish eagles drive off ospreys. When feathers are analyzed stable isotopes of nutrients brought in by river herring, eels and lampreys show up.”

Had John Muir been alive to witness the failure of Atlantic salmon recovery in the U.S., he might have amended his famous quote as follows: “When we try to recover anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe.”

Something to think about Fact is way back before dams where even thought of my great great grandfather a big fisherman said his father father caught Atlantic + Steal head and kings using smelts in rivers Madison Farmington west brook caught by stick line

he had farm in ct the fact is those fish ran together and protected the eggs Connecticut is missing out on large return funds the shame no one sees it it help bring more jobs to Connecticut. From out of state lic sales A transfer of our river water in tanks to New York hatchery and make a deal to start a spawning in numerous rivers Connecticut. And Thames river and brached rivers would not take much effort and yet give great rewards to ct residents. Smelts and bait fish have to be done in this process. Not only the alantic salmon are going to populate. Right now strippers are eating everything. Which there is no lack of strippers I don’t understand. Strippers are eating everything. Lobsters bunker shad small blues it not right people are catching 50 to 70 fish a day but of course releasing them all alive. But some one getting it wrong ask John skinnier

If everyone has given up on the Connecticut River for Atlantic salmon, perhaps introduce the adaptable

Chinook and Coho Salmon from the West Coast. These two salmon types adapted very well to the Great Lakes and their rivers. It’s a shame to waste a great river that has been cleaned up.

I’m not sure that preserving Lampreys is a great idea especially with the fish populations so vulnerable. Just a thought.

Hello,

It is terribly disappointing that the Atlantic Salmon restoration efforts south of Maine have more or less failed after so many years. I suppose more dams need to be removed and streams reworked etc. but the fish simply aren’t returning after all these years. Climate change is not likely the issue. If the New England rivers are to remain void of Atlantic Salmon, perhaps then, Coho or Chinook Salmon, if introduced, may take hold. Coho and Chinook are hearty and have adapted to the Great Lakes very well. Why not replace the Atlantic Salmon with these great fish in the East Coast rivers?

Millions upon millions of Atlantic Salmon had been mercilessly removed over the last 200 plus years and they don’t seem to want to come back. Coho and Chinook could replace them and create new bounty for the Atlantic Ocean and the rivers and streams of New England.

Hi Steve:

Gotta disagree here. The hatchery smolts got beat up in the concrete raceways. Their fins were frequently little more than stubs. Smolts need good fins to make it to Greenland. It’s true that the fry had lower survival to adulthood, but when they smoltified their fins looked like you could shave with them. And even with that low survival we got more smolts for the money with fry than by raising them in a hatchery. Finally, there was an attempt to reinvigorate the stock with fish from the nearest salmon river — Maine’s Penobscot. By 1980 we’d built the Connecticut River run to 529. The fish were doing great in freshwater. Then they vanished into a saltwater black hole. I don’t think there was a genetic bottleneck. These fish had to negotiate an increasingly warm Long Island Sound, then go around Cape Cod. I think they were victims of climate change.

Web: You raise a good point. Stripers have not benefitted significantly from fishways because they don’t use them much. But they certainly have benefitted from dam removal and especially from a lavish supply of forage fish such as eels, shad, alewives and, in Maine, smelt and blueback herring.

Striped bass have benefitted too, correct? And these eels are the ones they love to eat out in the salt, correct?

Thanks,

Web H.

Thank you Ted Williams. This in depth reporting needs to continue.

One reason for the decline in salmon returns to the Connecticut River was the switch in the 1980s from producing smolts (7 to 9 inch fish ready to head out to sea) to producing much more inexpensive fry. Fry have much lower survival to adulthood and that is when Connecticut River returns began declining until they had almost petered out. By the early 2000s it’s possible the remaining population became genetically bottlenecked and no attempt was made to reinvigorate the stock with crosses from the same Maine salmon stocks used in the initial push to replace the extinct Connecticut River stocks.

A truly excellent article. It highlights the fragile and often unrealized links that make for a robust & successful ecosystem. Allowing one or more of these links (such as the removing of lampreys for example) to be exploited or impacted can have a truly devastating effect.

Our water resources are already under enormous threat. I fear that many, including the current administration, have very little comprehension or interest in protecting them beyond self serving needs for privatization & exploitation.

Very interesting Article . I agree that the removal of dams and / or installation of fish passes for Salmon has benefitted other equally valuable migratory species . I had read of the “northward” drift of Salmon as Salmon rivers in Northern Portugal and Northern Spain are suffering , I believe , a similar situation with a real possibility that they will become extinct to Atlantic Salmon soon due to global ( sea ) warming ) Also , as an interesting by – product of global warming , Russian Pacific Salmon are running into rivers across the whole of Northern Russia into Northern Norway as the Ice which was always present even in Summer has melted and there is no longer a barrier between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans now in the Barents and Kara Seas. I with the efforts on the Connecticut River could be replicated in the Longest River in the British & Irish Islands namely the Shannon whose Salmon runs were destroyed by the Electricity Generating Board ( “ESB”) in 1927 when a massive dam blocked off access to the Middle and Upper Shannon . The “ESB” are supposed to ensure the easy passage of Salmon upstream but have failed miserably in that objective . A great Salmon River that had “Portmanteau” Salmon ( Huge 35 lbs plus fish ) was lost.

On Maine’s Kennebec River, the removal of the head of tide Edwards Dam in 1999 had a major impact on the Atlantic sturgeon and river herring populations. We now have Kennebec sturgeon populating other estuaries in Maine and the 2016 spring run of alewife is approached four million adults. The American shad population has also grown into an excellent fishery. Unfortunately we are still fighting for our Atlantic salmon, including litigating against a defective interim recovery plan proposed by the National Marine Fisheries Service.

Gasp… you mean there’s an ecosystem under water? Who’d have thunk! 🙂